My visit was shrouded in secrecy. No one was to know where I was going. So we met beside a nondescript bank in Kyiv to ensure the taxi driver did not discover our destination. I was led along a cluster of ordinary streets filled with residential blocks, offices and shops — and sharply told to stop my questions when we passed a woman walking her dog. Then, suddenly, we ducked down into a basement and I was ushered through a heavy door.

I found myself in a clandestine white-walled workshop cluttered with shelves of tools, boxes of machine parts and spools of wire. Here, a handful of men in their 20s and 30s were making some of the most sophisticated military drones on earth. The future of warfare was being built before my eyes.

A Buntar 3 drone was there on a table with its wings removed. It looked like a big model aircraft, with its grey fuselage and tail propeller. But these craft, almost four metres long, are highly complex machines that cost up to $100,000 each. They take off and land vertically using four wing-mounted rotor blades before flying like conventional aircraft with a range of 80 kilometres. They can remain airborne for more than three hours. The carbon-fibre body contains a $30,000 camera with thermal imaging capabilities to detect enemy positions day or night. This is backed up with sophisticated software created from combat experience that integrates tools to monitor altitude, weather and terrain with the Delta battle management platform used by Ukrainian forces, which links to artificial intelligence systems.

There were 31 small stickers on its fuselage — 23 black ones marking its test flights and 8 red ones denoting combat missions on the frontline of the grim war despoiling the biggest country in Europe. Bohdan Sas, the firm’s 26-year-old co-founder, showed me around a rabbit-warren of rooms, pointing out carbon fibre being painstakingly layered, compressed in vacuum packs and spray-painted, explaining how they had created specialist software to speed and simplify military operations.

- Bohdan with a Buntar 3 drone which can cost up to $100,000. Photo: Ian Birrell.

Welcome to the weapons factory of the future. For this is not just the sort of place where the war in Ukraine might be lost or won. These fast-evolving drones are changing the way that battles are now fought the world over. “In places like this, we are pushing the boundaries of warfare and reconnaissance,” says Sas, who started his career in technology as a teenager linking dumbbells to fitness trackers. “Because of the war, both Russia and Ukraine have developed their drone technology incredibly quickly.”

Buntar Aerospace — set up two years ago, spread across several locations and also making cheaper reconnaissance craft — is one of about 250 such drone-makers that have sprung up across Ukraine. Some are buried like this one in basements, others are located in smart IT office hubs or crumbling former Soviet factories. Together they reveal how the art of war is evolving with amazing rapidity in this country as unmanned land, air and sea vehicles reshape 21st-century combat. Innovative firms and creative brains are disrupting the defence industry in a world where even homemade drones can destroy expensive military aircraft, ships and tanks. “Right now there are only two countries in the world that really know how to fight this new type of war — Russia and Ukraine,” says Sas. And as I was told by several Ukrainian experts — from defence analysts through to frontline drone operators — this should be causing grave concern in Europe.

The new military age dawned at the end of 2020 in the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, fought between Armenia and Azerbaijan, when waves of drones turned the tide of the battle in a mountainous region that traditionally favoured defenders. The fighting lasted just 44 days — unlike the previous conflict between these two former Soviet republics that lasted six years — and resulted in decisive victory for Azerbaijan. Its drones, bought from Israel and Turkey, destroyed air defence systems, armoured vehicles and artillery forces on the ground. They provided speed and intelligence with control and communications systems that hoovered up data and helped determine targets at lightening speed.

Ukraine and Russia began using drones for intelligence and targeting after the Kremlin’s initial invasion of Crimea, with Russia developing an initial lead through exploiting Israeli technology. But Ukraine had also invested in Turkey’s Bayraktar drones and used them to great effect in repelling the mechanised Russian forces attempting to seize Kyiv three years ago. Yet as one Ukrainian drone operator told me last week, comparing the craft from 2022 — such as one that buzzed me in the Donbas trenches days before Moscow’s full-scale invasion — with those dominating today’s battlefield is “like comparing rocket science with the horse and cart”.

For Ukraine, necessity has been the mother of invention. As it fights for its survival, the nation has become a world leader in drone manufacture and warfare by exploiting previous strength in defence manufacturing, engineering and technology. “Ukraine has now started to be the creator of a new military doctrine,” says Mykhailo Samus, a military analyst and new generation warfare expert who argues that this arose from a need to deploy asymmetrical tactics against a much bigger foe. “We are fighting drone-centric warfare with drones now conducting different roles including first as the intelligence to find clear coordinates of the enemy, then of course as the weapon itself but also as the command and control system. So if you look at drones, they are weapons that can find and destroy.”

“For Ukraine, necessity has been the mother of invention.”

Samus points out that the “kill cycle’” — the time it takes between obtaining co-ordinates of an enemy position, transferring this information to command and control, then taking the decision to fire a missile to destroy a target — can now be just a couple of seconds. This can be devastatingly effective and far less cumbersome than the old methods of battle.

So while all the tanks and trenches we see on news reports are eerily redolent of previous wars, this conflict offers a glimpse into a future of highly automated fighting. “This new doctrine changes all our understanding of military tactics”’ says Samus. “So it’s very important to have our own European understanding of this future, the battlefield future of war. This is the new reality.”

Yet the frequencies used to control drones and send back footage often change weekly in cat and mouse games with enemy-jamming systems — something impossible on many traditional military systems or civilian drones. So both sides are in a constant race to keep up with their adversary’s advances. Nations at war, I am told by one Ukrainian official, must “innovate or die”.

In a war dominated by drones, electronic warfare is both critical and complex. Bear in mind that until recently, armed forces relied on a handful of jamming stations to throw a ring of protection around their frontline. Ukraine’s military had fewer than 100 such systems — and they relied on the standard 900 megahertz frequency typically used for civilian drone telemetry. But now battlefield drones can use frequency bands ranging from 100 to 12,000 megahertz. Different frequencies, however, require different signal generators and antenna to detect and jam them.

So the following day I visit an electronic warfare company helping to shape this new reality of warfare. Unwave, formed less than two years ago, has 100 staff inside an old factory in Kyiv region who are churning out thousands of jamming devices each month. Walking round the factory, I find small clusters of workers building an astonishing array of devices from sophisticated, multi-channel jammers designed for fixing onto armoured vehicles, through to smaller backpack-carried systems and handheld devices to alert soldiers to nearby drones costing $300 each.

- Tetiana at the electronic warfare factory. Photo: Ian Birrell.

“The idea is for every person on the frontline to have a device like this — it’s an absolute necessity, like having a helmet or gun,” says Taras, the firm’s product manager. “If you go into the dead zone there might be hundreds, maybe thousands, of drones flying overhead. Yet when we talk about this being a drone war, it’s really a war of frequencies. It’s about finding the frequencies and evading the frequencies.”

This felt like a more familiar factory set-up with men and women clad in blue overalls, some making metal antenna but others operating 3D printers or peering through microscopes at intricate electronic parts. They seem driven by similar motivation. Sergii is a burly former builder from a devastated border region. “It’s more than just work for me,” he tells me, choked as he tells of his pride in helping his nation and friends in the military. “It is not like going to work and getting some money — I’m helping those who defend us.” Tetiana, who is using a magnifying glass to check circuit boards placed in drone detectors, only joined the firm earlier this month. For her, it is personal with a brother fighting and friends of her husband killed by the Russians: “I wanted to do something useful. I love my country, I want to live here and I don’t want to leave.”

The mood of resigned self-sufficiency amid turbulent geo-politics is striking. Such is the agile desperation of this nation caught in an existential fight for survival, that this firm produces its own batteries to reduce reliance on China. I am shown classified projects being built in case critical support from the United States is lost. This firm is even manufacturing unmanned ground vehicles — flat-bodied with tracks and cameras — for de-mining, ferrying supplies and evacuating wounded. The boundaries of military technology are being pushed constantly — as Taras tells me: “This is far superior to what would have been around even two years ago. Much of this didn’t even exist then.”

Military procurement systems — infamously slow, bureaucratic, corrupt and profligate — must also innovate to survive when a nation is under such assault. Brave 1, the state agency that helped foster the birth of Buntar Aerospace, boasts of assisting 3,500 innovations from 1,500 “teams” since its own creation two years ago to respond fast to military needs. It collates demands from the frontline, then uses competitions and hackathons along with monetary grants to meet them. Such an approach is both disruptive and necessary in today’s theatre of war. “The period of life for a military system used to be maybe 30 or 40 years but now it is sometimes just three or four weeks before it’s taken over by another technology,” says Oleh Donets, who coordinates their links with Ukraine’s armed forces.

Ukraine is effectively crowd-sourcing frontline information to survive. And this method of invention has yielded some unexpected results, such as the development of interceptor drones to shoot down other drones. “It was like a crazy idea — drones to counter drones,” says Donets. They began with an ambition to destroy the low-cost Iranian Shahed that are now being mass-produced in Russia and used to overwhelm Ukraine’s air defence systems. After about nine months of working with a close-knit group of companies, however, they ended up developing devices that proved far more effective against Moscow’s reconnaissance drones — and are now shooting down about 1,000 a month of them.

- Inside a weapons factory. Photo: Ian Birrell.

At the start of this war, soldiers were tinkering with racing drones, adding explosives or grenades and then trying to drop them onto Russian positions. By 2023, it was reported that 10,000 drones were being destroyed monthly as both sides ramped up production. Last year, Ukraine produced 2.2 million, from basic drones flying short distances to aircraft flying deep into Russia to target arms dumps, munitions factories and oil refineries. President Zelensky recently claimed their engineers have designed a drone now with a range of 3,000 kilometres, which could hit even locations in Siberia.

Their biggest success, though, has been at sea, where a $250,000 craft loaded with 500 kilograms of explosives has shown it can sink a $300-million warship bristling with weapons. Kyiv’s maritime drones managed to defeat Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, pride of Moscow’s navy, forcing it to retreat from its Crimea base. They hit 17 air and sea targets, totally destroying 15 of them — striking five ships, six patrol vessels, two landing craft, two helicopters and, earlier this month, shooting down two SU-30 fighter jets using Sidewinder missiles. This was a step change in combat: the first time a surface drone brought down a combat aircraft.

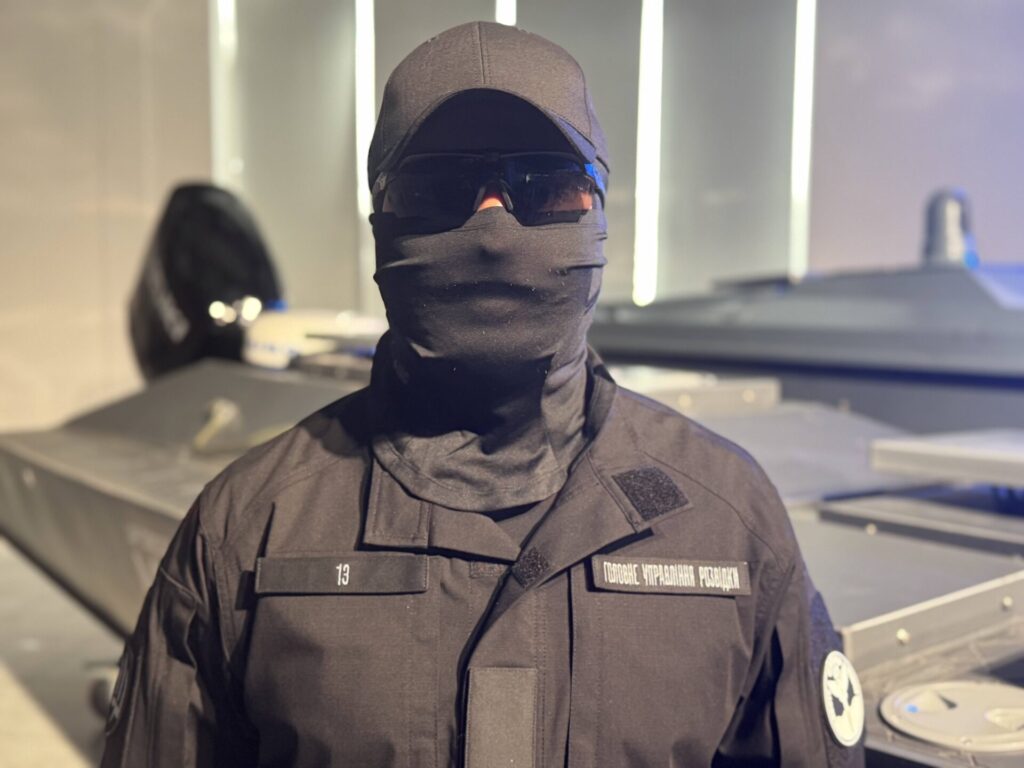

These sea drones — which entered service only two years ago — have been devastatingly effective, causing Russian losses valued at half a billion dollars. And Ukraine is proud of them. Last week in Kyiv, Lieutenant-General Kyrylo Budanov, their head of military intelligence, joined members of his secretive Group 13 special forces team to display the all-new Magura (Maritime Autonomous Guard Unmanned Robotic Apparatus) craft. Four models were on display: a ship “killer” capable of swarm synchronisation; a kamikaze vessel able to carry high loads of explosive; and two equipped with missiles and machine guns. One speaker at this slick event — which felt like the launch of a glitzy sports car, rather than a new robot army— hailed the arrival of “a modern fleet of the 21st century” while another described their success as akin to “the parable of David and Goliath”.

Members of Group 13 were there, faces masked by dark glasses and black balaclavas, and I ask them about striking enemy targets. “It’s like hunting — it is very difficult,” says Xena, a female member of the team. The team’s commander — known by his call sign Thirteenth — concedes that it had been challenging to create a new type of military vessel. “Previously, there was no such experience anywhere, there was no place to draw information,” he says. “These things completely change the philosophy of defence. They are changing the nature of warfare. No one was prepared for such a turn of events. Now many countries in the world, including Great Britain, are very quickly thinking how to reformat their fleets because they have turned out to be very vulnerable.”

- Group 13 with Thirteenth at front and Xena on right. Photo: Ian Birrell.

Ukraine simply cannot afford to be complacent in this field of battle. Russia is also finding new ways to harness military innovation and has proved effective at scaling up production as it shifts from its traditional top-down, monolithic approach in an economy retooled around war. The Kremlin has even introduced “drone studies” into classrooms to help produce the next generation of developers. It has taken a lead also in using fibre-optics — with filaments up to 40 kilometres long — to avoid jamming, showing how advances can be creative adaptation of existing technologies rather than innovative breakthroughs. As one Kyiv source tells me, “We shouldn’t underestimate them. They are changing, everything is changing.”

The rest of the world is watching, although largely left playing catch-up. In the United States, tech start-ups are seeking to similarly disrupt the huge defence sector with the invention of autonomous weapons, drone swarming and artificial intelligence. China, too, is investing heavily in such futuristic technologies — and is preparing to launch a high-altitude drone mother ship that can release 100 kamikaze craft. But where does this leave Europe? There is concern in Ukraine that it is failing to see the true threat posed by the Kremlin even as warfare is being so drastically transformed. One analyst tells me about meeting the head of a next-door nation’s navy at an annual defence conference. “Each time I ask him how many drones he has and he says they have three. That was maybe fine when he said it in 2022 — but not in 2023, let alone in 2025.”

Europe simply cannot afford to remain wedded to the old military technologies such as battleships and tanks, suddenly so vulnerable, or it risks becoming dangerously left behind. As I am told by Vadym Adamov, a 21-year-old drone specialist, it is impossible to imagine doing almost any tasks today on the battlefield without them. “We evacuate with drones. We are mining with drones. We are shooting with drones. We do everything with them. The only limit is your creativeness on how to use them.”

- Thirteenth, the commander of Group 13. Photo: Ian Birrell.

He believes this is a disruptive revolution in defence that bears comparison with the advent of the Guttenberg Press in the 15th century, “when words were taken from the hands of mighty people into the hands of ordinary people”. He points to a project he assists called Victory Drones, which has produced thousands of craft by teaching civilians how to make them. “In two weeks you can learn to assemble a drone with parts you buy yourself,” says Adamov. “You send it to the military and for $300, you’ve got a drone that can destroy a tank. Most of the stuff comes from China — it’s like Lego for adults.”

This young soldier, 10 years old when Russia invaded Crimea to start the war in Ukraine and a veteran of three years in combat, has little memory of living in a country without conflict. “So for me it is almost routine. You do not expect everyone to obey international laws — we see that if you have a big army you can go in, take what you want. There are no moral values in this new world. Now if Russia marches into Europe they will be really successful because they have learned all the lessons of modern warfare.”

He has a warning for us in Europe. “The first Russian rocket that hits your capital opens up a portal into a different world. When you find yourselves in this new world — and there’s more and more chance you will find yourselves here — you will be looking back at doing nothing for three years of the Ukrainian war. When I go to Europe and say to people I’m in the military, they say ‘Oh I’m so sorry’. But I say I’m sorry because we are on the verge of the Third World War and I should be sorry for you since you don’t know how to kill people with drones.”

Who knows if he is right in his fears about a Third World War? But his nation certainly bears the bloody scars of Russian aggression. And perhaps the ultimate irony is that one day soon we might end up looking for help from Ukraine in fighting to defend ourselves in the coming robotic techno-wars.

Additional reporting by Kate Hatsenko