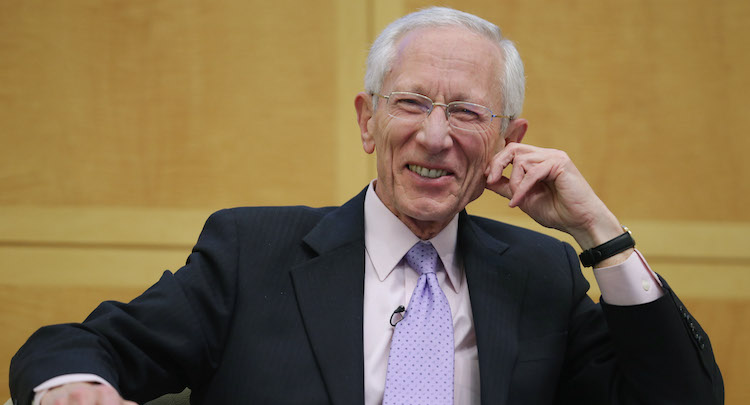

When we talk about Jewish statesmen, we usually refer to Israeli prime ministers, diplomats, larger-than-life military figures and the like. But Stanley Fischer, who died this weekend at 81, also deserves the title.

He saved Israel’s economy twice. Fischer, an immigrant to America from what is now Zambia, excelled at MIT and became among the more highly influential economics professors there (though his teaching career began at the University of Chicago). In the mid-1980s, Israel went into an inflationary spiral, a dangerous moment for the economy of a country that had not yet reached its 40th year. Fischer told Congress that Israel had to tackle its bloated government spending and the structural policies that made it a perennial problem. Otherwise, “the likelihood is strong that two years from now, she [Israel] will still be growing slowly, still fighting high inflation, and [be]more than ever reliant on outside aid.”

Fischer and Herbert Stein were recruited to help the Israeli government come up with an economic stabilization plan by George Shultz, Reagan’s secretary of state. Shultz once told me that his message to Shimon Peres’s government was: “We can help you, but you have to do exactly what we tell you to do.” Peres did. The bipartisan Israeli plan cut government, negotiated limits with the uber-powerful Histadrut labor union, and reined in Israel’s money-printing habits. It worked.

By the time Israel needed him once again, Fischer had done stints as the World Bank’s chief economist, the International Monetary Fund’s deputy director and resident crisis-management ace, and chair of MIT’s economics department. In 2005, Fischer was hired as the governor of the Bank of Israel, the country’s central bank.

Two years later, the global financial crisis hit. Because other major global currencies don’t depend on the shekel, Fischer could play with its value without bringing anything else crashing down. He also restructured the Bank of Israel’s policymaking process. Fischer instituted a round of quantitative easing to hold investment as steady as possible. But the shekel gained against the dollar as a consequence. This put stress on Israel’s exports, which accounted for a majority of the state’s GDP. So Fischer had the bank buy up large amounts of foreign currency to arrest the shekel’s rise without undoing the steps he had taken to stabilize investment.

Again, it worked. “While other countries fell deeper into recession,” Dylan Matthews wrote in 2013, “Israel brushed its shoulders off.”

Fischer was an Israeli hero, and not just to Jewish Israelis. Matthews notes a rather incredible detail: Fischer was so popular among Arabs too that several Arab states backed him in an unsuccessful bid to lead the IMF in 2011, despite the fact that he was an Israeli citizen and Israel’s top financial figure at the time.

Eventually, he would come back to America and join the Federal Reserve board, serving as its vice president under Janet Yellen.

There’s a company that makes figurines of various heroes in Jewish history, with a special focus on Israel and Zionism. They have figures of the great political leaders, military heroes and Zionist intellectuals. Perhaps one day there will be a matching action figure of the great warrior of monetary policy, Stanley Fischer.