“In war-torn Asia, Tibetans have practiced non-violence for over a thousand years…” So begins Martin Scorsese’s epic 1997 drama Kundun. Denied filming in India, dropped by Universal, disavowed by its eventual distributor Disney as a “stupid mistake” that alienated China, its release was almost miraculous. Yet, for all its merits, its opening claim, far from being a scrupulous summation of Tibetan history, still stands out as one of the more sensational exhibits of the seraphic spell radiated by Tibet’s most illustrious export: Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama.

Tibet was never a particularly peaceable place. Its empire, at its summit in the 8th century, extended to northern India, western China and central Asia. The Arabs, making inroads into the neighbourhood, were awestruck. And China, in the words of an inscription memorialising Tibet’s conquest of the Tang Chinese capital of Chang’an in 763, “shivered with fear” at their mention. But, peaking early, Tibet decayed over subsequent centuries into a reclusive hagiarchy. In 1950, when Mao’s Red Army marched in, Tibet possessed neither the vocabulary to parley with the communists, nor the capacity to resist them.

Tenzin Gyatso, identified in 1937 as the reincarnation of the 13th Dalai Lama, was hastily confirmed as Tibet’s supreme ruler at the age of 15. His court, spurned by the outside world, watched helplessly as Mao’s “peaceful liberation” of Tibet unfolded in earnest. Monasteries were razed, monks executed, thousands of peaceful protesters massacred — with many more detained, starved, tortured, and carted away to communes to toil in conditions so brutal that some resorted to cannibalism. In 1959, the Dalai Lama, facing imminent capture, escaped to India with his entourage.

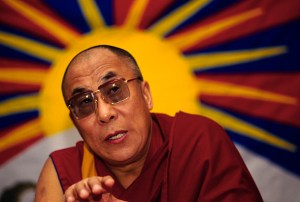

Since then, he has devoted himself to the preservation of Tibetan culture and the emancipation of Tibet from Chinese shackles through exclusively nonviolent means. Last week, in the lead-up to his 90th birthday yesterday, His Holiness resolved the critical question of his succession by stating explicitly that the next Dalai Lama will be identified by a trust founded by him. Exactly three decades ago, Beijing disappeared the Panchen Lama — second only to the Dalai Lama in the Tibetan pantheon — and replaced him with their puppet. China, officially atheist, is determined to appoint its own Dalai Lama once Tenzin Gyatso finally dies. By proclaiming his will to “reincarnate” in a body born in the “free world”, the Dalai Lama has given his institution a shot at survival. Yet as he enters his 90s, it is no insult to ask what his celebrity has done to secure the Tibetan people and their mutilated homeland.

Tibet today has the distinction of being the world’s largest colony. In official Chinese documents, it is classified as “Water Tower Number One”— a source of prized minerals and hydropower. Since annexing Tibet, Beijing has relentlessly disfigured it. It has mined and carted away its mineral wealth, dammed and diverted waters from its bountiful rivers, herded innumerable Tibetans into communes, stamped out the expression of Tibetan identity, and annihilated whole ways of life.

An exhaustive report published some years ago by Human Rights Watch documented how Beijing has corralled millions of Tibetans into rows of identical-looking apartment blocks called “New Socialist Villages”. A more recent study, by the Tibet Action Institute, details the coercion of children as young as four into boarding schools to be intensively Sinicised. When they come home, they lack the language to communicate with their Tibetan-speaking parents. To Tibetans, this is only the newest phase in a long campaign to purge their identity. The sinisterness of Beijing’s conduct is exceeded only by the crassness of its propaganda. A captive Tibet is proclaimed as being free, the suppression of its language is justified as a necessary condition of its integration, and the destruction of its culture is trumpeted as evidence of its progress.

Hundreds of Tibetans — monks and lay people alike — have sought to draw attention to the plight of their land by immolating their own bodies. Consider Tsulrim Gyatso, a highly respected scholar at the Amchok monastery in Gansu, driven to despair by all he saw around him. “Tears drop from my eyes when I dwell on this state of sufferings,” he wrote in the winter of 2013. Later the same day, Gyatso walked to a busy intersection, doused himself with petrol, and lit his body on fire. As the flames consumed his flesh, Gyatso folded his palms in a gesture of respect: the tender final act of a Tibetan Buddhist who believed, like so many before and after him, that his calvary would stir the world beyond into some form of action. I have often wondered how the world may have reacted to Gyatso and his brethren had they chosen to blow themselves up among crowds of civilians in Shanghai. Might they have incited debates on the “root causes” of Tibetan “militancy”, and ignited protests in solidarity with their cause?

Despite preventing his people from adopting violent methods of resistance, the Dalai Lama has been branded a “terrorist” by China. A message from him in 2008, when an uprising against Chinese rule erupted in Tibet, would have paralysed Chinese administration in the region. His choice, instead, to calm the protesters, by invoking Buddhist precepts of nonviolence, resulted in no gratitude or offer of negotiation from his people’s tormentors. As he writes in his most recent book, Voice for the Voiceless, “Chinese Communist leaders have only a mouth to speak but no ear to listen”.

Beijing’s refusal to deal with him has eroded some of his authority within the Tibetan community in exile. Certainly, the Dalai Lama continues to be revered as a spiritual leader by almost all Tibetans, and their veneration only intensifies as age reveals his mortality. But many also see in China’s unyielding push to eradicate their identity a confirmation of the futility of nonviolence — a central pillar of the Dalai Lama’s teachings. As far back as 1988, he downgraded his demand for full independence from China to limited autonomy within its boundaries. Nearly four decades on, his homeland of six million people remains, alongside Xinjiang, the most intensely policed territory under Chinese rule. A young, restless generation of Tibetans is turning inwards, casting doubt on the movement that has so far failed to deliver anything for them.

And it is difficult to fault them. Over the decades, the Dalai Lama has travelled from capital to capital, picking up major accolades — including the Nobel Peace Prize — and interacting with well-meaning film stars, activists, and politicians. But what does he have to show for it? He admires Lincoln, but Lincoln was consequential only because his words, as Julia Ward Howe put it, were “writ in burnished rows of steel”. He admires Mahatma Gandhi — but Gandhi, as even Tibet’s most famous dissident writer Shokdun concedes, fought a system that had “some degree of moral conscience”. The CCP is not the British Raj. To say that His Holiness has kept his homeland’s cause alive while not being able to halt the slow erasure of Tibet itself is not to impugn him: it is to recognise that our world, which kowtows to votaries of violence while treating pacifists as comical curios, is what it is.

Even at the height of his fame in America, the Dalai Lama was seldom regarded as anything more than an exotic spectacle, the Oriental Pope expected to dispense morsels of easily digestible Eastern spirituality. He became anything “we would like him to be”, the late British-Indian historian Patrick French once observed. Barring notable exceptions, his supposed champions barely knew him. Larry King once introduced him to his audiences as a Muslim. Sharon Stone opened another event by calling him “Mr Please, Please, Please let me back into China”. Western Publishers minted fortunes selling books with his name on the cover, then sent 1% of the profits to his office.

For its part, the West, rapidly secularising and becoming more and more dependent on China, has grown less and less enamoured of him. The earliest omen of this denouement was Richard Nixon’s visit to China in 1972. Desperate to gratify his hosts, the US president abruptly terminated the CIA’s covert assistance to Tibetan resistance. This did not in itself make a great difference: the purpose of the programme, which cost Washington about $2 million, had always been to use Tibetans to gather intelligence on China, not to help them regain their homeland. What did make a ruinous difference to Tibet, however, was the international acceptability Nixon’s summit conferred on Mao.

The Mao who received Nixon, and whom Nixon exalted in self-clowning tones as a visionary statesman, was by then responsible for more bloodshed than any other leader of the 20th century. After all the death and devastation he had supervised in Tibet, Xinjiang, and China proper, Mao entertained himself by being vulgar, vile, and vicious even to the people who served him. When told by his physician that the procession of young women brought to his bed were being hospitalised with infections because of his appalling hygiene — Mao refused to rinse his body or brush his teeth — the Great Helmsman replied: “I wash my prick in their cunts.” The powers that fraternised with Mao were sooner or later going to teach themselves to overlook the victims of the regime he erected. The Financial Times garlanded Mao’s successor, Deng Xiaoping, as its “Person of the Year” two years after he presided over the massacre of 10,000 pro-democracy protesters in Tiananmen Square.

By then, a self-serving consensus for closer relations with China had crystallised in the West, which, it was claimed, was more likely to influence China by partnering with it — by creating a prominent position for it inside global institutions. Especially after the fall of the Soviet Union, the US locked itself into a self-destructive trade relationship with the People’s Republic. Advanced economies, underwriting Beijing’s rise by incinerating the jobs that supported their own working classes, scattered the seeds of explosive discontent at home to export material prosperity to a regime that converted it into hard power: to wield against its own benefactors.

This rationale has come back to haunt the West. Far from moulding the Chinese state’s behaviour, it is the West that has incrementally relinquished its own professed values to propitiate Beijing. It is Western authors who self-censor for the tawdry privilege of being published in China. It is Hollywood that modifies its films to placate the Chinese censors. International agencies that performatively hector others lose their voice when dealing with Beijing. And governments that never tire of puffing their chests at the Middle East’s tinpot tyrannies in the name of human rights flee from the Dalai Lama for fear of offending China.

Even India, home to the largest community of exiled Tibetans, is terrified of crossing China by appearing too supportive of their spiritual leader. Narendra Modi’s government, for all its bellicose nationalism, has not endorsed the Dalai Lama’s right to decide his succession. Even before Modi appeared on the scene, it was a tradition in New Delhi to invoke penal codes dating back to the British Raj to lock up anyone of Tibetan appearance during a senior Chinese dignitary’s visit to India. Still, the profoundly worshipful attitude of Indians to the Dalai Lama — the global face of a faith that originated in India — has deterred successive governments from stamping on his acolytes. It is chilling to contemplate their fate when the Dalai Lama is gone.

This is one reason why the Dalai Lama spent the past two decades modernising the Tibetan resistance movement and equipping the exiled community with the means to continue without him. He has weakened his own office, fostered political institutions distinct from the spiritual branch he oversees, and subordinated himself and devolved his powers to them. Tibet now has a government-in-exile that is democratically elected by a highly organised diaspora. Now, by pronouncing emphatically on his succession, His Holiness has ring-fenced an institution that has sustained Tibetan identity for centuries. Is this sufficient to guarantee its survival, and will the United States and India forever refuse to endorse a successor handpicked by Beijing? Their past behaviour does not encourage optimism.

This is a truly grim moment for Tibetans. The figure who has held their nation together is fading away, while the tenets upon which his struggle was premised have so far produced no results. His long-suffering people are now torn between the precepts of their faith and a longing for home, which, 75 years after its seizure by China, looks more unrecognisable, and out of reach, than ever.

a.appcomments {

background: #FFF;

border: 1px solid #446c76 !important;

font-family: benton-sans,sans-serif;

font-weight: 600;

font-style: normal;

font-size: 12px;

color: #446c76 !important;

padding: 12px 50px;

text-transform: uppercase;

letter-spacing: 1.5px;

text-decoration: none;

width: 100%;

display: block;

text-align: center !important;

}