The debate over the justice and necessity of the American Civil War is reflected not only in the volumes of the scholars but in the minds of some of our important poets. Most kept insisting on what was for them a prior conviction, a kind of recognition, which can only lead to a condition of bathos. For example, William Cullen Bryant boasted of the heroic farmers-turned-soldiers in his rather jingoistic poem “Our Country’s Call”:

Our country calls; away! away!

To where the blood-stream blots the green…

Strike, for that broad and goodly land,

Blow after blow, till men shall see

That Might and Right move hand in hand,

And glorious must their triumph be!

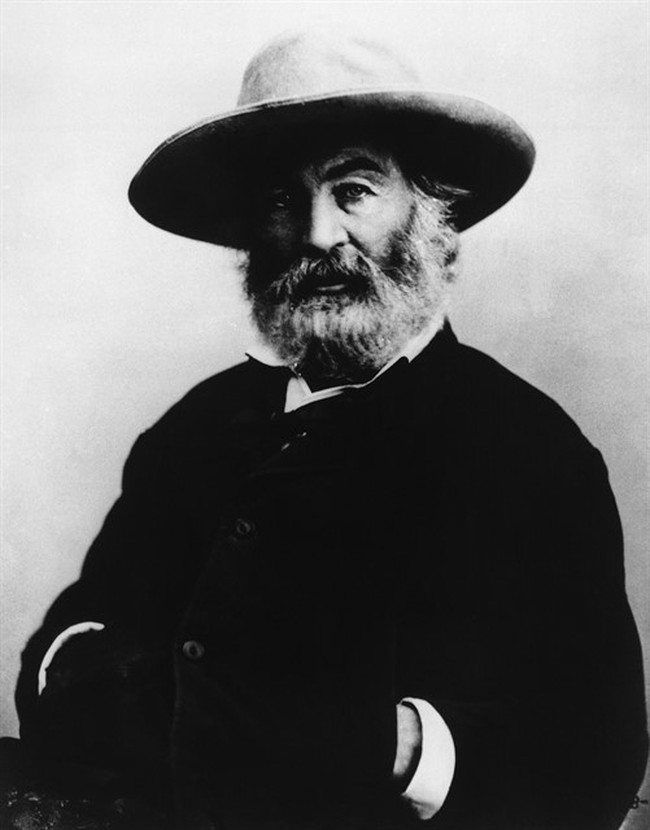

These lines were written by a man who was handy with a pen rather than a rifle, a man of the sort whom Walt Whitman later dismissed as a “pale poetling seated at a desk lisping cadenzas piano,” a man whose simplistic and contrived boosterism is reminiscent of those eloquent talkers who never faced an enraged mob or a double-barrelled shotgun taking a bead. It’s a one-way drop from the sublime to the ridiculous.

In the same way, John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem “Ichabod” (“inglorious” in Hebrew), contra the Fugitive Slave Law and mourning the treachery of Daniel Webster, is, for all its grieving ardor and cosmetic wisdom, entirely academic. A central quatrain encapsulates the poem’s burden:

Oh, dumb be passion’s stormy rage,

When he who might

Have lighted up and led his age,

Webster wished to perpetuate the Union even at the expense of slavery, failing which the most destructive war in American history was launched, from which the nation has never fully recovered. But Webster did not light the fuse. For Webster, as he stressed in his famous “Seventh of March” speech before Congress in 1850, the supreme issue was to preserve the Union whole for it could never be dismembered peacefully. Indeed, writes Robert C. Byrd in his encyclopedic volume of classic Senate speeches, “Webster viewed slavery as a matter of historical reality rather than moral principle…Webster urged northerners to respect slavery in the South and to assist in the return of fugitive slaves to their owners.” Webster believed in the sanctity of the Union but was not prepared to unleash a holocaust upon the nation. Versifiers, obviously, are not always to be trusted.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.’s view of the war developed from a degree of abolitionist skepticism to complete approval. His main concern was for the preservation of the Union, as in “Brother Johnson’s Lament for Sister Caroline,” as if he endorsed Lincoln’s backward belief in the First Inaugural that the Union preceded the states that met to form it.

She has gone,-she has left us in passion and pride

Our stormy-browed sister, so long at our side!

She has torn her own star from our firmament’s glow,

And turned on her brother the face of a foe!

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow is a cut above these pro-Union poets. Though clearly a Lincoln man, poems such as “A Nameless Grave” and “Killed at the Ford” come to symbolize, in the words of blogger Susannah Fullerton, “all the beautiful young men whose lives were lost in that terrible war.” In the latter poem, there is no indication of which side the dead soldier belonged to. But as a man of the North, Longfellow did not grasp the sordid calculations that lay behind the triggering of the war and the reason why these “beautiful young men” had to be reduced to carrion.

It is easy to be a booster when you don’t know the details and are convinced of your own moral purity. The only solution is a certain degree of self-deprecation, a desire to know more, and an unwillingness to surrender to the apparently obvious.

Thus, in his capacious book “Patriotic Gore,” critic Edmund Wilson wrote: “The celebration of current battles by poets who have not taken part in them has produced some of the emptiest verse that exists.” There are exceptions, of course, but on the whole these poets are the intellectual sumpters of war. One applauds the war-hating author and veteran Robert Graves’ summation in a draft poem, contrasting:

…the froth of the city

The thoughtless and ignorant scum

Who hang out the bunting when war is let loose

And for victory bang on the drum

With:

The boys who were killed in the battle

Who fought with no rage and no rant

…peacefully sleeping on pallets of mud

Low down with the worm and the ant.

One recalls the scarifying passage in his “Good-bye to All That” in which a British and a German soldier, locked in mortal combat, had impaled one another with their bayonets. One can transpose in imagination to a similar emblematic scene in which a Union and a Confederate soldier die in agony together, skewered on one another’s blades.

Among our more contemporary poets writing in prose, Carl Sandburg’s saccharine “Storm Over the Land” passionately espouses the Union cause—according to Wilson, “one is tempted to feel that the cruelest thing that has happened to Lincoln since Booth shot him has been to fall into the hands of Carl Sandburg”—while Edgar Lee Masters’ “Lincoln: The Man,” dedicated to “the memory of Thomas Jefferson,” is perhaps the most venomous and controversial of biographies, condemning the “tyrannous plutocracy” of a “demagogic” president. These qualify as the bookend perspectives on Lincoln and the war.

The greatest and most interesting poet of them all is Walt Whitman. His earlier poems in “Leaves of Grass” enthusiastically celebrated the Union cause—BEAT! Beat! drums! blow! bugles! blow! His zeal and exhilaration for the war seemed unstinted. But as a military hospital volunteer, experiencing the stink and butchery of the battlefield, Whitman’s attitude gradually grew more sombre. The bugles grew muted in his imagination and were replaced by the groans of the dying and wounded. His poem “A Sight in Camp in the Daybreak Gray and Dim” tells the real story:

A sight in camp in the daybreak gray and dim,

As from my tent I emerge so early sleepless,

As slow I walk in the cool fresh air the path near by the hospital tent,

Three forms I see on stretchers lying, brought out there untended lying,

Over each the blanket spread, ample brownish woolen blanket,

Gray and heavy blanket, folding, covering all.Curious I halt and silent stand,

Then with light fingers I from the face of the nearest the first just lift the blanket;

Who are you elderly man so gaunt and grim, with well-gray’d hair, and flesh all sunken about the eyes?

Who are you my dear comrade?Then to the second I step—and who are you my child and darling?

Who are you sweet boy with cheeks yet blooming?Then to the third—a face nor child nor old, very calm, as of beautiful yellow-white ivory;

Young man I think I know you—I think this face is the face of the Christ himself,

Dead and divine and brother of all, and here again he lies.

“There isn’t a flag but clings ashamed and lank to its staff,” he wrote in “Memoranda During the War.” Time spent on the battlefield had turned a passionate supporter of the war into its harshest critic. The vision he could never shake was of a mound of offal that turned out to be “a heap of feet, legs, arms, and human fragments, cut, bloody, black and blue, swelled and sickening, a full load for a one-horse cart.”

This was America’s original sin, launching headlong into a war that need not have been fought. As Jeffrey Hummel acutely remarks in “Emancipating Slaves, Enslaving Free Men,” “The Civil War represents the simultaneous culmination and repudiation of the American Revolution.” Its repercussions persist in a kind of perverse continuity in the divisive animosities and free-floating execrations that bifurcate the nation even as we speak.

It explains the flurry of claims and counterclaims regarding horrendous acts of Civil War slaughters flying fast and furious. Plainly, there were atrocities on both sides—how could it be otherwise? We hear a lot about the massacre at Fort Pillow in current topical literature, for example, the details of which are still disputed in many quarters, but far less about the St. Louis massacre or the destruction of Atlanta, Vicksburg, Fredericksburg, and the Shenandoah Valley, chronicled with chilling precision in Walter Brian Cisco’s “War Crimes Against Southern Civilians.”

Cities were razed, homes burned, prisoners shot, and citizens gunned down. “Vast sections of the state were uninhabited by war’s end. ‘We believe in a war of extermination,’ said Brigadier General James H. Lane.” Why should this be is a rhetorical question. Why is the conduct of the war taken for granted, almost without question? After all, the war and post-war history, at least initially, is almost always celebrated by the victors, as everybody knows, their tactics and strategies are assumed as necessary. Sifting through the data and relevant materials over a long lapse of time requires a degree of scrupulosity that is almost beyond the call of scholarly duty.

Perhaps more crucially, the shock wave of that infernal event explains the residual enmity between North and South; the toppling and covering of Southern monuments; the suppression of whites, chiefly males, in competition with so-called marginals, often at the expense of talent, competence, and merit; the malign effect of Critical Race Theory and diversity mandates upon the educational system and infrastructure; and the perpetuation of the sentimental and misguided narrative of Lincoln as a legendary figure whom neither our self-esteem nor our moral credentials can allow to be called into question, and which has corrupted the teaching of American History from the ground up.

But nothing can justify the internecine cruelty of the war, the wanton bombardment of civilian centers, and the wholesale slaughter of the flower of American youth on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line, drenching the soil of the homeland with the blood of its own people.

Editor’s Note: Do you enjoy PJ Media’s conservative reporting that takes on the radical left and woke media? Support our work so that we can continue to bring you the truth. Join PJ Media VIP and use the promo code FIGHT to get 60% off your VIP membership!