Dishonesty is a notoriously difficult thing to research. That may be why it is also, hilariously, the subject of some of the larger recent scientific fraud scandals. Francesca Gino, a significant figure in that area, was fired this year for allegedly falsifying data in studies about cheating — the first tenured Harvard professor to be removed in 80 years. I can’t help but admire Gino’s chutzpah in writing a book called Rebel Talent: Why It Pays to Break the Rules at Work and in Life while breaking the rules at work and in life.

It’s not just Gino. Her co-author Dan Ariely, who is even more famous, was also accused of making up data, including in one of the same papers. The study found that people were less likely to lie about their car mileage on insurance forms if they signed an honesty pledge at the top, rather than the bottom, of the form. Although Ariely denies fabricating it himself, the mileage data on that study had been very obviously made up with a random number generator.

There is something deeply splendid, as the data sleuths who uncovered the problems noted, about all this: “We were, like, Holy shit, there are two different people independently faking data on the same paper. And it’s a paper about dishonesty.”

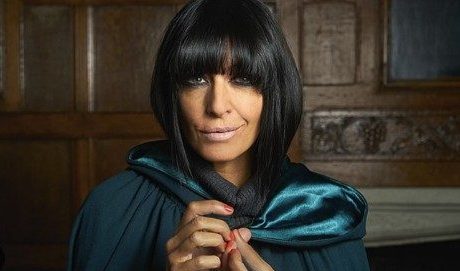

If we can’t trust the scientists, then who can we trust? How about reality TV? The Traitors is back again this week, and what’s fascinating about the show is that you get to see something very rare: people lying, in high-stakes situations, where you know that they’re lying. It is, I would argue, an excellent research opportunity.

The hugely successful game show is essentially a parlour-game murder mystery: there are 25 or so people in a Scottish castle. A subset of the 25, perhaps three, are designated “traitors”; the rest are the “faithful”. The traitors must remain undetected, while, every so often, “murdering” — i.e. evicting — one of the faithful. The faithful, meanwhile, must winkle out the traitors; in daily roundtable meetings, they vote on who they think the liars are, and the person with the most votes is also evicted, whether faithful or traitor. At the end, if only faithfuls remain, they share a pot of up to £120,000; but if there are any traitors left, they take it all. Still with me?

It is compelling viewing. We, the audience, know who the traitors are, so we get to see the faithful flailing around, making weird leaps of logic and spreading unfounded suspicion around like a virus. But more interesting is how we get to see the traitors themselves — if they’re good — wearing their two faces: playing the faithful off against each other, being subtle little Machiavels, twisting words and pulling strings. Telling, basically, bare-faced lies. Honestly, sometimes it’s hard to watch.

It’s dishonesty on open display, which is surprisingly rare and surprisingly uncomfortable. It’s shocking. All the more so when you see how the excellent liars build the trust of the faithful. Perhaps our fascination with the programme is because we spend so much of our lives trying to work out whether someone is being straight with us, whether we can trust that salesman or that builder or that would-be lover; it is refreshing to see someone unambiguously lying. And it gives us a chance to learn about how dishonesty manifests.

This isn’t something we can really do under research conditions — partly because it’s so difficult to get ground truth. Here’s what I mean by that. If you’re researching, say, the efficacy of a cancer screening test, you run your test on a bunch of people who either have cancer or don’t, and you see whether the test correctly identifies them. But you can only do that because you know, separately from what the test says, who really has cancer and who doesn’t. That’s ground truth. Without that, your ability to assess the accuracy of your test is severely limited.

For example, in the US, law enforcement agencies still regularly use polygraph tests – “lie detectors”, in popular parlance. The FBI and CIA use them to screen employees; local and federal police use them to interrogate suspects, although the evidence is rarely admissible in court. But there’s a problem, which is that we don’t know if they work.

The idea is that they measure stress: heart rate, breathing rate, blood pressure, and “galvanic skin response” (that is, how well your skin conducts electricity, which is a proxy for how much you’re sweating). And, in theory, someone who’s lying is going to be more stressed than someone who is telling the truth.

There are all sorts of problems with this idea, of course, not least the fact that being interrogated by the police is probably pretty stressful, whether or not you’re lying. But one really crucial one is that we don’t really know whether lying is more stressful, because most of the time, we don’t really know who’s lying, and when we do know, the lies aren’t very stressful ones.

Real-world research into polygraph testing relies on confessions as ground truth. That is, when a suspect fails the polygraph test, they are confronted with the results. If they then confess to the crime, the polygraph is considered to have been vindicated. But there’s a problem: the polygraph’s results are used to pressure the suspect into confessing. So if they pass the test, they won’t be asked to confess; and if they fail the test, they might get pressured into confessing even if innocent. The method is “virtually guarantee[d]” to find that polygraphs work, even if they don’t, a 2008 paper said, because the test result and its verification are not independent. It’s as though the accuracy of breast cancer screening was verified by whether it convinced the patient that she had cancer, rather than whether she actually did.

The other way of assessing polygraphs is in the lab. You might get half your subjects to commit a fake crime — stealing money from a closed room, for instance. Then you polygraph the participants, and say that if they can convince the test that they’re innocent (whether they are or not), they will win some money, say £50; the idea is to create genuine motivation to beat the test. You have your ground truth then; you know who’s lying, because you told them to lie. But now it’s only £50. It’s not going to change anyone’s life. The stakes are low, so the stress is low.

So we have two opposite problems, a kind of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle of lying. Either you can have a realistic, high-stress situation but no ground truth, or you can have ground truth but no real stress.

I’ve used polygraphs as the example here, but the same problems apply to all research into how we lie. Do people behave differently when they are lying? There are lots of claims about eye contact, about voice pitch and tension, about language choice — do liars use hedging language like “to be honest” or “as far as I can remember” more?

There’s an entire field of research into “micro-expressions”, fleeting facial movements we apparently make when we’re concealing an emotion. (There’s another problem, which is that like a lot of the research in this field, when it’s not fraud, it’s mainly garbage. The guy behind the “micro-expressions” idea claimed to have discovered people he called “wizards” who could tell liars just by looking at them, but it was basically rubbish.)

This matters. People’s dishonesty has huge consequences! How many people have, for instance, trusted a builder to renovate their house and then learned that they’re a cowboy? How many people are taken in by Ponzi schemes or crypto scams? More obviously the entire legal system turns on whether or not people are telling the truth. Some more reliable way of knowing whether someone believes what they say might, for instance, be very relevant in the notoriously he-said-she-said world of sexual assault cases. Politics… well. There’s a reason why there’s a book about politics called Why Is This Lying Bastard Lying To Me?

But again, this is hard to research, because when we do that research, either we don’t know whether people are lying, or we do know they’re lying, but only about some inconsequential thing in the lab which probably isn’t that stressful to lie about. I imagine lying in court, or lying in the dispatch box, is extremely stressful.

What researchers need is some sort of situation where people are known to be lying, on camera, for high stakes: perhaps for tens or hundreds of thousands of pounds. Obviously enough, that’s where The Traitors comes in.

Imagine if the contestants were hooked up to a polygraph and asked to beat it, in the knowledge that their results would be shared with the group. You couldn’t ask for a more direct, real-world test. It would be a small sample size, sure, but you could do several tests throughout the series and over several different series. And at least it would be valid. Better a small, but good, test than a huge one that’s entirely uninformative. You could do all sorts of other tests: linguistic and facial analysis, thermal imaging to detect changes in blood flow, eye-tracking to see where people look when they lie.

Of course, the whole idea only works when the stakes are genuinely high. And that’s why it won’t work at all for the current series — a celebrity series where they’re all playing for charity money and public goodwill, which I’m worried might render the whole thing a bit silly. Does Stephen Fry or Paloma Faith really care enough about the outcome to publicly stab somebody in the back? They’d only be hamming it up in any case. Will the other contestants care enough about the backstabbing for it to really hurt, anyway? Probably not. The whole point is that it needs to be nobodies for whom the money really matters, and so they are willing to debase themselves to win it.

Learning about dishonesty — actually learning about it, properly, not doing the fake crap research that is most of what is out there — could have profound impacts. Obviously not all of them would be good; imagine what governments and corporations would do with a ministry of truth. But it’s a huge part of human life, and we don’t really understand it. So, dishonesty researchers: when you’ve finished faking the data for your current studies, please do go and ask the BBC if you can do some proper research.

a.appcomments {

background: #FFF;

border: 1px solid #446c76 !important;

font-family: benton-sans,sans-serif;

font-weight: 600;

font-style: normal;

font-size: 12px;

color: #446c76 !important;

padding: 12px 50px;

text-transform: uppercase;

letter-spacing: 1.5px;

text-decoration: none;

width: 100%;

display: block;

text-align: center !important;

}