Writing of Bill Clinton accepting plane rides from Jeffrey Epstein, former Tatler and Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown described private plane travel as “a true satanic temptation from the mountaintop”. There is, she says, “no one you wouldn’t kill, betray, or sleep with to ensure a lifetime of luxe relief from the armpit of mass transit”.

Brown’s insight is a potent one: the real moral hazard behind ultra-high-end luxuries such as private plane travel is the way they stand for exclusive access. An invitation to travel by private plane symbolises inclusion in what C.S. Lewis called “the Inner Ring”: the aspirational set, the ones in the know, the insider group within which everyone longs to be included. And among the infinite poisons leaking from the Epstein scandal into every level of public life, one of the most noxious is the moral inversion at its heart.

Private-jet luxury is, ultimately, about an Inner Ring of comfort and snobbery; the Epstein story, though, presented a far headier temptation. The private jet filled with extremely young girls, known as the “Lolita Express”, represented corruption in the fullest sense. For this Inner Ring, the initiatory ritual required at least tacit assent to if not active participation in the sexual abuse of very young girls. The defilement of youth and innocence was the point.

And this moral inversion cuts to the heart of the modern world. For Epstein’s network simply took the training-wheels off a moral outlook that has come, by degrees, to govern the entire modern West: one that does not simply reject but actively seeks to desecrate the older, Christian value-system, in pursuit of a morality of power, violence, and individual desire.

One of the earliest and frankest exponents of this moral inversion was also, and not by coincidence, also a trailblazer in the literature of ritual sexual abuse: the Marquis de Sade. Justine (1791), written during one of his numerous stints in prison for sexual crimes, details the suffering and eventual death of Thérèse, a homeless 12-year-old orphan girl, who keeps trying to be virtuous but receiving only violence, cruelty, and sexual torture at the hands of everyone she turns to for help. The message, exhaustively hammered home by de Sade’s characters through lengthy interspersed passages of philosophical debate, is that the world is fundamentally godless and amoral, and there exists no governing force save power, violence, and untrammelled individual desire.

It is, in the precise sense, a satanic worldview. Justine was banned by Napoleon, and did not appear in English translation until the 20th century. But especially since the Sixties, de Sade’s radical libertinism and rejection of all moral constraints has come, by degrees, to appear almost ordinary. So much so that, in recent decades, it’s begun to look as though at least some segments of contemporary society view Justine less as a provocation than as an instruction manual.

I doubt the perpetrators in Britain’s euphemistically named “grooming gangs” have read the Marquis de Sade. But his pitiless libertarianism has, by now, seeped into the Western groundwater, not least via the entrancing image-making vector of the global porn industry. In some respects, of course, especially the widely acknowledged ethnopolitical dynamic to the crimes in some areas, these gangs are bound up in specifically British pathologies. But I also suspect that if my benighted country ever manages a full reckoning of these atrocities, we will find many parallels with the Epstein network — not least in the victim profile, and also, perhaps, the function of the abuse itself.

“I doubt the perpetrators in Britain’s euphemistically named “grooming gangs” have read the Marquis de Sade.”

Just as in Justine, at the heart of these crimes is the pitiless exploitation of vulnerable girls desperate for love and protection. Girls in care, or with cruel or chaotic homes, absent or abusive fathers. Girls who had already experienced been molested. As Julie Bindel shows in a recent investigation of London’s rape gangs, the most salient feature of victims is often less their ethnicity than their lack of trusted, loving adult care.

The same went, too, for Viriginia Giuffre. In Nobody’s Girl, she describes a childhood scarred by abuse at the hands of everyone who should have cared for her. She alleges that her father sexually molested her from the age of 7 to 11, including trading her to a family friend. As a result of this, her behaviour worsened so much she was sent to a deeply abusive “treatment centre” where she was once forced to eat her own vomit.

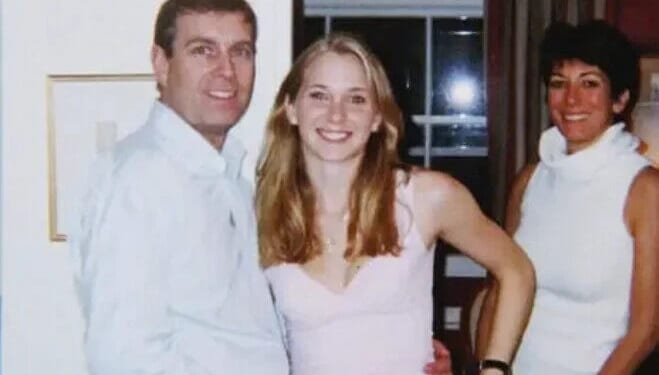

It is, like Justine, a miserable litany of abuse: after escaping this setting she lived a semi-itinerant life, punctuated by routine rape at the hands of strangers and acquaintances – before, eventually, she was returned to her father. He then found her employment at his workplace, Trump’s Mar-A-Lago club in Florida, as a towel attendant — only for her to be spotted and groomed there, by Ghislaine Maxwell and Jeffrey Epstein. “For 10 years,” she writes, “men had cloaked their abuse of me in a fake mantle of ‘love’. Epstein and Maxwell knew just how to tap into that same crooked vein.”

Some are already seeking to discredit her story; there are defamation lawsuits, and Prince Andrew, with whom she claims to have had sex three times, called her a “fantasist”. Who is right? Speaking of the efforts by some literary critics to downplay the Marquis de Sade’s colourful personal life, the radical feminist Andrea Dworkin remarked in Pornography that whether or not you think he did anything wrong is really a question of whether whether or not you are generally inclined to believe de Sade or the women who accused him of sexual abuse.

Radical feminists might also note out that the unhappy story Giuffre maps — the pattern of abuse, neglect, and desperate longing for refuge with trusted parent-figures — is one that reappears with grim regularity among rape gang survivors. Giuffre recounts how Ghislaine Maxwell seemed a warm mother figure to her — but also, from the very first “interview” aged just 16, forced her into sex with Epstein, and later his and Maxwell’s wealthy friends, while herself sometimes joining in.

There is an unnerving parallel in Justine, in the passage where Thérèse is rescued, or so she thinks, from prison by Mme Dubois, a murderer — only to find Dubois coercing her to join the gang by offering to protect her, before shrugging or even joining in, as the male gang members sexually abuse her. The Marquis de Sade’s cold message of amoral power-worship, and remorseless crushing of compassion, is summed in the ruthless words message the gang gives Thérèse about her predicament: “[Y]ou must serve either our pleasures or our interests; your poverty imposes the yoke upon you, and you have got to adapt to it.” It’s hard not to think of the working-class girls groomed, raped, and ignored for years, or simply dismissed as “slags”. Whether the abusers drove taxis or flew by private plane, the profile of the girl was similar; the recruitment was through simulated affection and care.

And the use to which the victims are then put follows the same profoundly evil pattern. I choose the word “evil” carefully, as I mean specifically acts that set out intentionally to negate, to destroy, and to desecrate. Whether in the ultra-luxurious setting of Epstein Island, or on squalid mattresses in crumbling British provincial towns, the group-based sexual abuse of very young girls functioned as a form of social bonding, through ritual de-humanisation of the desperately vulnerable.

Giuffre describes her own treatment as a thing, as Epstein and Maxwell passed her around “like a platter of fruit”. She also describes wishing for the evacuation of her selfhood: during sex, she says, Epstein subjected her to “so much pain that I prayed I would black out”. And she recounts how her abusers simply saw this as part of her job. When, she alleges, one former minister choked, beat and bloodied her, Epstein, merely said coldly: “You’ll get that sometimes.” Like the rapists in a de Sade story, Epstein simply viewed it as his right to make her suffer at will, simply because he was powerful and she was not. And as in de Sade, her torment was intended to be anti-morally instructive: a means of reinforcing the conspiratorial unity of the Inner Rings that practiced these secret, shared acts of cruelty and libertine, amoral defilement.

Again: like the de Sadean moral worldview, this kind of group bonding is satanic in the precise sense of the word. It is also extraordinarily potent. We can reasonably suppose the Inner Rings thus fostered continue to endure, whether — in Britain — among the rape gangs that remain active to this day, or among the Epstein elite. Indeed, the degree to which Prince Andrew, now no longer the Duke of York, has been hung out to dry, likely attests more to his relative political irrelevance than to the depth of his corruption, extensive though this doubtless was.

Like Harry, Andrew is a junior “spare”. With tastes as extravagant as his natural abilities are sparse, he has spent his life humiliatingly scrabbling and tin-rattling to make up the shortfall. He is embroiled in the Epstein corruption for the same reason he has always been a royal liability: he wants a lifestyle well beyond his capacity to earn legitimately, and is thus a dear friend to anyone with the money (and the jet) to keep him in the Inner Ring style to which he’d like to remain accustomed.

It is not difficult to imagine a parasite of this calibre viewing the thoughts and feelings of trafficked teenage girls as being of roughly the same importance as those of the maids who cleaned his hotel suite. Giuffre claims that Andrew acted “as if he believed having sex with me was his birthright”. Andrew himself has always strenuously denied these encounters, though Giuffre later took him to court in a case the prince settled in 2022, for an undisclosed sum, without admitting liability.

Virginia Giuffre died earlier this year, reportedly by suicide. Meanwhile, the ongoing shadiness surrounding the whole Epstein network, the mysterious suicides and disappearing video footage and all the sordid rest of it, leaves one wondering how much of the Inner Ring remains intact even as ex-Duke of York Prince Andrew writhes in the media spotlight.

So should we greet this all, glumly, as vindication of the pitiless de Sadean worldview, and its rejection of any refuge or compassion for the victim? Is it true that there’s really nothing but power and desire? I think not. Giuffre’s story is subject to all manner of challenges and attempts at revision. She cannot push back; she is dead. But though she didn’t manage to bring down the entire Inner Ring, I think Giuffre was, ultimately, stronger than those who sought to de-humanise her. Her insistence on having her story heard, on being understood as a person, serves as the most potent rebuttal of all to the de Sadean morality of pure, pitiless power and desire.

Her abusers took Justine as their moral template, and sought to consolidate their Inner Ring by ritually reducing living humans to mere objects. It is a profound evil; the networks thus produced are still with us, as is de Sade’s godless libertarianism. But Giuffre’s insistence, in Nobody’s Girl, on having her story heard was her final act of defiance, of stubborn humanity. The depth of pity and anger her story has inspired, and the shockwaves it is still producing, on its own stands as proof that the Marquis de Sade was wrong.