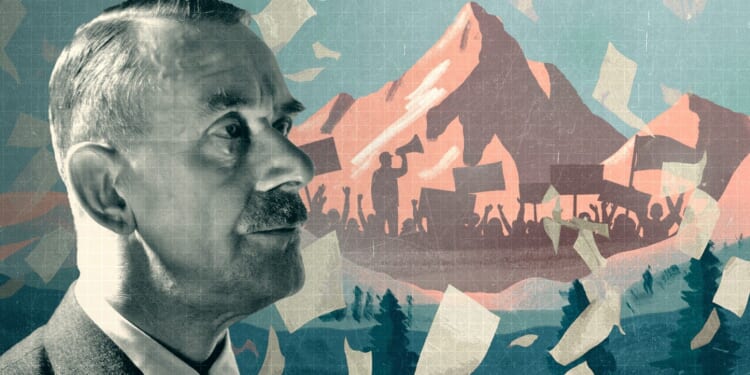

The Polish poet Adam Zagajewski once asked: “Isn’t it true that we’re still dealing with the heroes of The Magic Mountain?” More than 100 years after it was first published, Thomas Mann’s great novel feels as contemporary as ever. So, too, does the story of how Mann wrote it. Inspired by a visit to a Swiss sanatorium in 1912, the author completed it after 11 years, a world war, and the political paroxysms of the Weimar Republic.

Today, as the established order appears to be crumbling all around us, The Magic Mountain speaks directly to our sense of living through a rupture in time.

Mann wrote the first words of The Magic Mountain in 1913, intending it to be a short companion piece to his novella Death in Venice, published a year earlier. But then, swept up by the nationalistic fervor of Germany’s mobilization at the outbreak of World War I, he set aside the manuscript to dedicate himself instead to his reactionary essay Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man. It was published on the eve of Germany’s capitulation in 1918. An ill-timed defense of the deep well of German Kultur against the soulless materialism of Western civilization, Reflections was partly provoked by Mann’s older brother, the novelist Heinrich Mann, a liberal democrat and Francophile. When Heinrich published his antiwar essay “Zola” in 1915, Thomas perceived it as a personal attack. The two brothers did not speak for seven years.

Believing democracy to be “poisonous” to the German spirit, Mann appeared at war’s end to be in sympathy with the new German Right. When he returned to the manuscript of The Magic Mountain in April 1919, Munich was in the grip of a violent clash between communist revolutionaries and Right-wing Freikorps troops, including the future Nazi officers Ernst Röhm and Manfred von Killinger. As he began revising the chapters he’d written earlier, Mann could hear machine-gun fire and grenade explosions from his home in Munich’s Herzog Park neighborhood. It was during this time that he wrote the novel’s famous foreword, in which The Magic Mountain is described as a “time-novel” that takes place “long ago, in the old days of the world before the Great War, with whose beginning so many things began whose beginnings, it seems, have not yet ceased.”

“A life lived in the daylight of reason is somehow only half-lived.”

Hans Castorp, the novel’s young hero, arrives at the International Berghof Sanatorium in Davos in the summer of 1907. A young engineer about to embark on a career in ship-building, he intends to spend three weeks in the Swiss Alps visiting his tubercular soldier cousin Joachim Ziemssen, a patient at the Berghof, who early on warns his visitor that “a man changes a lot of his ideas up here.” By the end of the novel, when Hans Castorp leaves the sanatorium to fight, and most likely die, in the trenches of World War I, he has spent seven years at the Berghof.

One of the great achievements of the novel is its compositional subtlety, its use of the leitmotif, so that one learns to identify what Hans Castorp is thinking even when he is not himself aware of it. On his arrival, for instance, he is not quite aware of his existential and intellectual aimlessness, his nihilism. (As Nietzsche knew, one can well be a nihilist without actually knowing it). Only many hundreds of pages and several years later does Hans Castorp arrive at a possible answer. By then, he has received a kind of crash course in modern European civilization, listening to and “experimenting with” (the novel’s term for it) the ideas of a number of unforgettable characters. There is the Italian humanist Ludovico Settembrini, a liberal rationalist and firm believer in civilizational progress; the Russian temptress Clavdia Chauchat, who is a kind of Nietzschean apostate of the bourgeois order; and Dr. Edhin Krokowski, a psychoanalyst employed at the Berghof.

But the most remarkable character of all is Leo Naphta, a Jewish convert to Catholicism, who affirms the supremacy of the Roman church over the bourgeois state and bluntly justifies the use of violence and terror to goad humankind back under divine rule. At the same time, Naphta also espouses a communist dictatorship that, in his view, will help achieve “the ultimate goal of redemption: the children of God living in a world without classes or laws.” As Hans Castorp rightly intuits, Naphta is a reactionary who sounds, at times, proto-fascist in his terroristic contempt for the liberal bourgeois world. Even so, he is drawn to him for the same reason the reader is: because a life lived in the daylight of reason is somehow only half-lived. Naphta speaks from what Nietzsche called “the unexplored realm of dangerous knowledge,” which is what makes him so intriguing.

As a fictional creation, Naphta is Mann at his most prophetic. He is a product of the author’s having paid close attention to what was stirring in Germany in the years immediately after the war. Mann conceived of Naphta in 1922, around the same time that the industrialist and statesman Walter Rathenau was assassinated by two Right-wing terrorists in Berlin in broad daylight. Horrified by this, and other instances of Right-wing terror, Mann had begun a political reorientation that can be felt in The Magic Mountain. In October 1922, he gave a famous address to a group of German students in which he warned them against the emerging threat from the Right, with its “sentimental obscurantism” and “disgusting and crackbrained assassinations.”

“Perhaps a bildungsroman will strive to show that the experience of death is ultimately an experience of life, that it leads toward the human,” Mann said, before surprising everyone by affirming the democracy of the Weimar Republic.

The Magic Mountain, of course, is the very bildungsroman Mann was referring to. It was as if he needed to send Hans Castorp — and, by extension, himself — up into the mountain to work through the many ideological and spiritual conflicts the war left in its wake. And just as Hans Castorp, in a pivotal chapter, loses his way in a blizzard and is tempted to lie down in the snow and die, Mann, too, was tempted by what he called Germany’s “sympathy with death”: that cult of unreason that was its spiritual tradition. By the time the novel was published in 1924, he had recognized what that sympathy leads to and chose, instead, like Hans Castorp in the snow, to be on the side of life, to affirm the future, and to “grant death no dominion over his thoughts.”

In these reactionary times, with a nihilist occupying the White House, Mann’s embrace of humanism and democracy against the nihilistic death cult around him remains principled and courageous. The reader ascending the novel’s Olympian heights today should not expect an escape but an immersion in the world around us. The story of the novel’s genesis is also a story of Mann’s political courage. As Walter Benjamin wrote to Gershom Scholem after reading The Magic Mountain: “I can only imagine that an internal change must have taken place in the author while he was writing. Indeed, I am certain this was the case.” Though a conservative by temperament, Thomas Mann became a defender of democracy because he was so alarmed by what German conservatism was becoming.

Of how many people today can we say the same?

This essay was adapted from the author’s book, The Master of Contradictions: Thomas Mann and the Making of The Magic Mountain, which has just been published by Yale University Press.