At one point in 1991’s Silence of the Lambs, Hannibal Lecter (played by Anthony Hopkins) tells detective Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) that “there are three major centers for transsexual surgery: Johns Hopkins, University of Minnesota, and Columbus Medical Center.” Buffalo Bill, the woman-skinning serial killer Starling is pursuing, probably “applied for sex reassignment at one or all of them,” only to be rejected.

That bit about Bill’s rejection — the killer merely thinks he’s trans — is a relic from an earlier, hard-to-imagine age, when patients’ claims of belonging to the opposite sex were apparently subjected to rigorous scrutiny, rather than being readily affirmed. Yet the film’s dialogue fails the test of verisimilitude in one respect. By the time the events in Silence of the Lambs take place, in the 1980s, Johns Hopkins University’s sex-change clinic had been closed down.

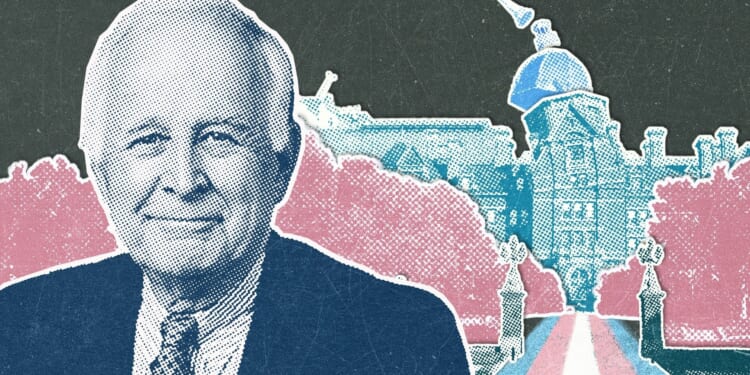

Dr. Paul McHugh, then head of psychiatry at the Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, made the decision to shutter it in 1979. The move “wasn’t controversial” at the time, McHugh tells me in a Zoom interview this week. There were dissenters, to be sure, not least John Money, the sexologist who’d established the unit a decade and a half earlier. But “all the other people at the hospital, even including many of the plastic surgeons, agreed.”

A colleague’s systematic follow-up study found that subjects who’d undergone reassignment didn’t show much by way of improvement in their “interpersonal relations” and overall well-being. In those days, McHugh recalls, the specialists who pioneered trans surgery didn’t really imagine that they were “turning a man into a woman.” They simply thought they’d make life “easier, more comfortable” for the patient.

But if the intended effects failed to materialize, what was the point? The enterprise, he reflected later, was akin to “collaborating with madness.”

In the ensuing years, McHugh maintained a distinguished career at Hopkins, even founded a program on human flourishing. Beginning in the late 1990s, however, gender-activist pressure mounted on medical researchers and practitioners across the West. The psychiatric field, in particular, was called to ratify a pair of highly speculative claims: that gender is largely a social construct, unmoored from biology; and that some people are “born into the wrong body.”

Both can’t be true at once. The second claim rests on the idea of gender identity as a meaningful, immutable characteristic of which a person can have a deep inner awareness. How can it then simultaneously be socially constructed? Nevertheless, many in the medical profession forced their minds to submit, the Law of Non-Contradiction be damned. Paul McHugh refused. After his term as department chair ended, in 2001, he continued to critique the new gender science, both through academic research and popular advocacy.

McHugh paid a price. By the mid-2010s, he’d emerged as the trans movement’s Public Enemy No. 1. The Human Rights Campaign in 2017 launched an entire website to “debunk” his work. The advocacy group GLAAD created an “accountability” profile on him (complete with an unflattering portrait) that busted him for claiming, among other things, that “gender ideology harms children,” and that transitioning kids is akin to performing liposuction on anorexics.

In 2016, The Advocate, an LGBT publication, described McHugh as a “notoriously antitransgender psychiatrist,” singling out his statements that “‘sex change’ is biologically impossible” and that “People who undergo sex-reassignment surgery do not change from men to women or vice versa.” A 2017 Washington Post article cheered the resumption of reassignment surgeries at Johns Hopkins, under the headline: “Long Shadow Cast by Psychiatrist on Transgender Issues Finally Recedes at Johns Hopkins.”

Then, in 2022, Johns Hopkins established a special board to rename programs and buildings that “recognize individuals whose legacies may now be considered antithetical to our values.” Soon enough, a postdoctoral fellow petitioned the board to rename the Paul McHugh Program on Human Flourishing on account of “his transphobic and homophobic views,” as a campus paper tsk-tsked.

But then, as the “peak-woke” fever broke, gender ideologues began to suffer setbacks. In Britain and across Europe, youth gender clinics have come under intense scientific scrutiny, in some cases leading the authorities to shutter them. Global athletic bodies, including the Olympic Committee, are rewriting rules that allow biological men to compete in women’s sports.

McHugh’s public reception altered once more, in tandem with these developments. In 2023, the university’s president, Ron Daniels, intervened to preserve McHugh’s name on his legacy program. “‘You can’t take the name off a program [associated with] an active faculty unless he’s had some infraction,’” McHugh paraphrases Daniels telling the university community. McHugh had a spotless record. Then, on Thursday, the 94-year-old McHugh received the Medal for Intellectual Freedom from the American Academy of Sciences & Letters, the country’s oldest learned society, founded in 1780.

McHugh has returned from the cold, in short. “In your mid-90s,” he tells me, “you expect people to not find you interesting. So the very fact that we’re talking is kind of fun for me.”

When Paul McHugh entered psychiatry, the battle over evidence-based medicine took a very different shape. It was the mid-1950s, when an Americanized, and particularly dull, brand of Freudian psychoanalysis almost totally dominated the profession. At Harvard Medical School, he recalls, “the brightest classmates of mine were drawn into psychiatry, psychoanalysis in particular. And I wanted to be with the bright boys, so I went along.”

As with every other branch of medicine, psychiatric training involved the memorization of a mountain of facts — which in those days, he says, meant “psychoanalytic facts.” But a Harvard mentor urged him to go in a different direction. The Freudians, the mentor told him, “get so tied up with themselves. They don’t know anything about the brain. You know, the brain must have something to do [with mental illness].”

McHugh was impressed enough to take a detour into brain science. He also had a stint at King’s College London, studying under the legendary psychiatrist Sir Aubrey Lewis, who “showed me exactly how to take a case … in such a fashion that you began looking for evidence to prove one thing right or wrong.” This, contra the Freudian method, which, he argues, starts with theory — the Oedipus complex, repression, and so on — and then searches for evidence in the case.

“The enterprise was akin to ‘collaborating with madness.’”

Upon returning Stateside, he became a champion of experimental, evidence-first psychiatry — and made enemies of swaths of the profession. “I began challenging things,” he says, “and people got really mad. I was surprised by the Freudian orthodoxy.” Each time he was up for a post, some half a dozen psychoanalysts would show up — in person — to militate against McHugh getting it. “Imagine giving up a day or two’s work to stop a guy from getting a job!”

He rose all the same. One early position was chairman of psychiatry at the University of Oregon, where he encountered his first trans cases. An Oregon colleague, Ira Pauly, a disciple of Money (who’d founded the Hopkins gender unit), was “encouraging sex-change operations out there.” Seeing the patients, McHugh says, “I thought they were caricatures of women. They were all men who wanted to be women.” His early conclusion: “I thought it needed research.”

When the Hopkins chairmanship opened up, it offered an opportunity for just such research. Once more, his hiring faced ferocious opposition from the psychoanalysts. Yet when he got the job, it didn’t occur to him to “cancel” the Freudians. He continued to maintain a psychoanalytic presence in the department, and funded the expensive training analyses aspiring Freudian therapists must undergo.

Beyond respect for differing scientific views, McHugh worried that if he ousted his intellectual opponents, the medical students he trained would come to suspect “that I had something to hide” — wisdom that would be lost on many others across academe in coming years, as censorship and cancel culture ramped up.

It was one of the Freudians, an analyst named Jon Meyer, who did the follow-up study on the gender clinic, finding that transgender surgery didn’t noticeably improve the lives of the men who underwent it (the cases then were almost entirely male-to-female). Three decades later, a Swedish study discovered that, as McHugh summed up in a much-discussed Wall Street Journal op-ed, “beginning about 10 years after having the surgery, the transgendered began to experience increasing mental difficulties. Most shockingly, their suicide mortality rose almost 20-fold above the comparable nontransgender population.”

Meanwhile, he conducted research in many other areas, including schizophrenia, pedophilia, and what used to be called multiple personality disorder, among other conditions. As the years wore on, experimental psychiatrists like McHugh would find themselves in a curious alliance of sorts with the Freudians, as both faced the fury of the anti-psychiatry movements promoted by the likes of Thomas Szasz in America and Michel Foucault and his disciples in Europe.

The idea was that mental illness is an invention of the institutions that treat the mentally ill, and that the institutions valorize themselves in the process. “Get rid of the psychiatrist, and you get rid of mental illness,” as McHugh sums up the anti-psychiatric creed, which he likens to the view that crime is a social construct used by the police and justice systems to maintain and expand their institutional power.

As he recounts in an essay published in the ’90s, McHugh encountered a medical student besotted with such notions. McHugh’s solution: he had the student spend half an hour with a patient diagnosed with schizophrenia. Afterward, the student sheepishly conceded that schizophrenia, and mental illness more generally, are very much real.

Yet too many others in the profession, McHugh worries, have gone along with such trends, culminating in psychiatry’s near-total surrender to gender ideology in the last decade. Instead of challenging patients’ misperceptions regarding themselves — something that, to their credit, orthodox Freudians also insist upon — “affirming” psychiatry actively colludes in the delusion and even justifies radical bodily modification to give it a semblance of “reality.”

“It’s the idea,” McHugh tells me, “that if your sense of yourself and the facts about yourself diverge, it’s the sense of yourself that [the clinician] has got to go with.” He adds: “That’s a kind of old idea, too. It goes way back to the Gnostics” — the Late Antique heresy — “where it was in a sense the spirit, not the flesh, that mattered.”

But what specifically explains transgenderism — the radical disjuncture between bodily sex and the patient’s subjective sense of his gender identity? As might be expected from an anti-Freudian, McHugh resists accounts based on hidden or distorted sexual desires. As a clinician, McHugh prefers to deal with conscious-but-deluded ideas that grip patients’ minds — especially dangerous in a cultural context that actively encourages the drive toward unreality.

In the event, McHugh believes that medicine’s knowledge of human sexuality is still in its infancy. “That’s really the problem,” he says. “We don’t understand the connections that tie us one to the other…. We should be studying and debating these things. But, you know, there are a lot of answers people don’t want to hear, so they don’t ask the questions that need to be asked.”

Nothing could’ve been more harmful to this project than the anti-scientific moralism that took hold of elite institutions in the 2010s. “In the old days,” McHugh recalls, “I used to have conversations with people who thought I was wrong now and then. But at the beginning of the 21st century, it was no longer that I was wrong. It was that I was evil.” You didn’t debate evil during peak woke — you extirpated it.

Yet as the fog of gender fanaticism lifts, McHugh looks like the one who remained clear-eyed. His triumph is a testament to the enduring capacity of rigorous, pluralistic scientific inquiry to self-correct, adjusting course in the light of the evidence, and withstanding even the most intense ideological agitation. “I think that really is the only way to go,” he says. “Realism and the recognition that all this disdain for traditional facts, biological facts in themselves, is not going to get anybody anywhere.”