Forming Americans who are worthy to carry on the country’s legacy.

The great civilizations of antiquity have never needed a majority to survive. They have always required just a quorum of men who knew what they believed and acted on the courage of their convictions. A few hundred trierarchs at Salamis, a few thousand hoplites at Thermopylae, a Roman handful who backed Scipio when everyone else wanted to sue for peace—a hearty few have helped preserve their respective ways of life in times of turmoil.

The American Founders understood this. Fifty-six merchants, farmers, and lawyers in Philadelphia signed their own death warrant, and 12,000 half-frozen men at Valley Forge kept that signature from being erased. Formation of character is about learning how to stand when everyone else sits down. We don’t study great men to cosplay greatness—we study them to see how a group of determined souls can change the world.

Today’s America, however, no longer forms leaders. It manufactures influencers and administrators. Its schools churn out credentialed mediocrities fluent in therapy and management but strangers to duty, tragedy, or honor. The republic’s elite, once shaped by Scripture and Cicero, is now shaped by LinkedIn. The result is a leadership class without leadership, a caste of clever children managing the ruins of their inheritance.

The crisis isn’t institutional—it’s human. The old republic assumed that man could govern himself. But that kind is nearly extinct. The rot began not in Washington but in the schools that teach resentment, the homes that fear discipline, and the pulpits that mistake affirmation for faith.

The remedy isn’t nostalgia for Christendom or some museum exhibit of “Western Civ.” It’s the formation of character: the slow, deliberate business of making a person who is capable of governing himself, and therefore a polity.

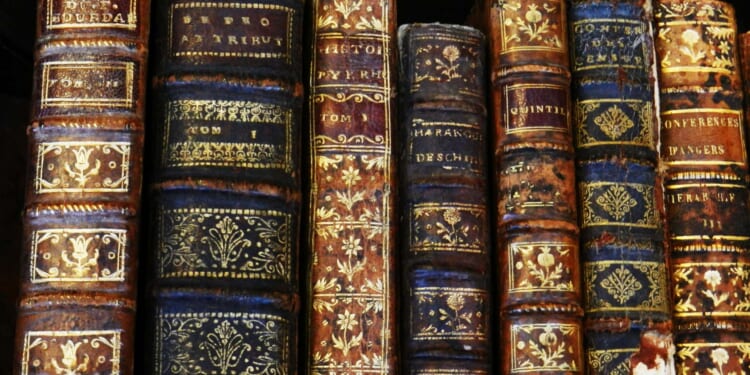

To drink from the classics is to recover the very virtues that our republican way of life demands. The Greek starter kit was simple enough: logos—reason ordered toward truth; aretē—excellence for its own sake; sōphrosynē—self-command; and the polis—responsibility in common. The classical man read Plato for justice, Aristotle for virtue, Thucydides for tragedy, Polybius for institutions, and Marcus Aurelius for the schooling of the will. These weren’t coffee-table ornaments; they were the blueprints for building the inner architecture of a citizen.

Themistocles read the wind and bullied Athens into the straits at Salamis, turning a city of farmers into a sea power. Xenophon woke before dawn, decided to become the man the Ten Thousand needed, and marched them home. Alexander, coached by Aristotle, aimed not just to conquer but to fuse worlds. Scipio carried a war to Africa and, having won, showed sōphrosynē, mastering himself when he could have humiliated Rome’s enemy.

The point isn’t hagiography; it’s permission—to attempt, to organize, to dare. In the classical world, greatness and restraint were inseparable; you ruled others only after ruling yourself. These are the minimum requirements for civilization.

The classical inheritance wasn’t Europe’s alone. Across the Atlantic, the American experiment drank from the same spring. Washington was hailed as Cincinnatus for restraint. Adams read Cicero to learn the duties of a citizen. Madison, Hamilton, and Jay argued like Romans about factions, offices, and law in The Federalist. Tocqueville saw that institutions float on habits formed long before statutes are passed. These classical measures met the republic’s better religious energies. Courage was yoked to limits, ambition was answerable to judgment, and liberty was disciplined by reverence. It was a living grammar, producing men who knew that freedom without a proper moral foundation soon degenerates into a mass of individuals with unbalanced appetites.

America’s generals were heirs to the same tradition. Robert E. Lee, schooled at West Point when Latin and moral philosophy still shaped a man, read Plutarch’s Lives and Marcus Aurelius until duty became instinct. His letters breathe that Stoic air—self-command, reverence, and the conviction that honor isn’t pride but proportion. “Duty, then, is the sublimest word in our language,” he wrote, echoing Marcus Aurelius’s injunction: “Do every act of your life as though it were the very last act of your life.” Though defeated on the battlefield, Lee carried himself with a Roman dignity that turned surrender into an act of moral victory.

Ulysses S. Grant, Lee’s opposite in temperament, was no philosopher, but the same formation ran in his marrow. He wrote like Caesar: plain, spare, factual, and untouched by ornament or self-pity. His Memoirs possess that austere honesty the ancients called gravitas. Where Lee personified Stoic resignation, Grant embodied virtue—the quiet courage to endure, to press on after failure, and to be magnanimous in victory.

Their causes divided them; their formation united them. Each, in defeat or triumph, acted as the Romans would have understood: disciplined, modest, untheatrical. They were the last products of an education that taught duty before ideology and character before charisma—a republic that still produced adults.

Abraham Lincoln was the fullest heir of that classical-Christian synthesis. Self-taught yet steeped in Scripture and Shakespeare, he read Plutarch for moral example and Euclid for clarity of thought. His prose carried the cadence of the King James Bible and the balance of Cicero—conviction yoked to proportion. He governed as a moral realist, knowing that power without conscience curdles into cruelty.

A generation later, Theodore Roosevelt carried the afterglow—the civic vigor of the ancients translated into the idiom of a modern republic. He read Marcus Aurelius before breakfast and packed Thucydides for the campaign trail. He preached “the strenuous life” not as swagger but as moral hygiene: the cultivation of character through action. Both men understood what every serious republic eventually forgets: comfort is corrosive, and courage must be disciplined by duty if freedom is to survive.

Now, a century and a half later, we find ourselves governed by adolescents with résumés, heirs to a civilization they can’t quite explain and managing institutions they no longer believe in.

For a century, public life still drew on that inheritance. It gave the republic its moral accent: restraint without weakness, confidence without arrogance, reverence without cant. But when the dialogue between Athens and Jerusalem fell silent—when we stopped forming the conscience before training the will—the result wasn’t liberation but drift. We kept the machinery of democracy yet undermined the metaphysics that made it run. The gears still turn, but nothing moves.

Great men read great men; that is the West’s quiet relay. Yet emulation is not idolatry. It is an apprenticeship across centuries. A civilization that withholds exemplars withers into management. A culture that hands its boys Plutarch, Polybius, and the Psalms and expects them to imitate the lessons therein, raising men capable of building households, companies, regiments—and republics.

The West once married classical ideals to religious conscience. Joined together, they produced moral seriousness yoked to intellectual ambition; pulled apart, they rot into sentimentality or cruelty. Our present elites manage the worst of both: moral vanity without belief, cleverness without character. They mistake empathy for virtue and activism for sacrifice. They can quote statistics but not Scripture, deliver lectures on equity but never on excellence. They’ve inherited the architecture of civilization but lack the inner scaffolding to hold it up.

If recovery comes, it will come by standards. Civilizations are saved by the souls they form. Formation must again become a public project: education as the cultivation of virtue, art as the expression of order, institutions as schools of judgment.

To speak of “formation” is to maintain our source code. Standards look like a curriculum that restores logic, rhetoric, and history through biography; Great Books seminars where students argue instead of emote; arithmetic and geometry as the grammar of order; and memory work that teaches the mind to hold meaning. In the household, this looks like a common table with a common book, with children reciting what is worthy. In the polis, this happens when apprenticeship and skilled trades are honored, jury duty is treated as civic liturgy, and service and sport form bodies fit to carry souls. These are the operating instructions of a free people.

Leadership begins long before power, in the quiet disciplines of reading, imitation, and restraint that make a person worthy of command. When the next crisis comes, America won’t be saved by slogans or platforms, but by men and women formed to recognize the hour, and who can bear the weight of duty and act.

Our forebears called such people citizens. We might simply call them adults.