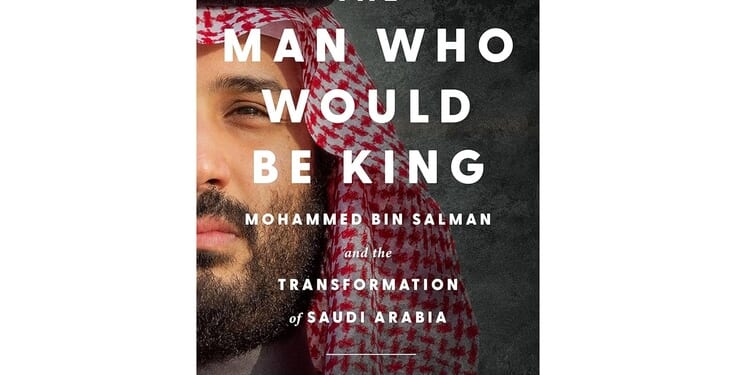

Napoleon Bonaparte was once asked what makes a good general. His alleged reply—”audacity, audacity, always audacity”—made it onto the long list of sayings attributed to the French commander. It is less clear, however, whether these attributes make for a good ruler. But as Karen Elliott House shows in her new book, The Man Who Would Be King: Mohammed Bin Salman and the Transformation of Saudi Arabia, we might just find out.

A longtime observer of the Middle East in general, and Saudi Arabia in particular, House is well positioned to examine the Saudi crown prince. She draws from both her extensive contacts and experience in the country, as well as interviews with the crown prince himself, his friends and family, and his critics. What emerges is a portrait of a supreme risk taker who sees the necessity of change in the kingdom and views himself as destined to be its change agent.

Mohammed bin Salman is young, a mere 40-years-old. Should he succeed his father, the 89-year-old Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, he will in all likelihood be the youngest king in living memory. MBS, as he is known, is cut from a different cloth than many of the Saudi monarchs of the last half century. And, as he is well aware, the kingdom faces many challenges.

“In order to understand a man,” Napoleon purportedly observed, “you must understand the world when he was 20.” MBS came of age amid a turbulent time. In 1979, jihadists seized the Grand Mosque of Mecca. More than 600 militants held the holy site, and the kingdom was ultimately forced to rely on French special forces to end the siege. Hundreds were killed and hundreds more wounded in what would prove to be one of the seminal moments in modern Saudi history. MBS wasn’t born yet, but he would grow up living with its aftermath.

The Grand Siege, as it has come to be known, led to the kingdom making a fateful pact with more religiously fanatical elements, including influential clergy members. As House notes, the first Saudi state (1744-1818) owed its rise to a pact made between Muhammad bin Saud and the religious leader Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. The former provided the troops and the military wherewithal and the latter provided the ideology and fervor. Pacts between the Saud family and Wahhabist ideologues helped lay the basis for the second (1824-1891) and third (1932-present) Saudi states, as well.

But after the siege, the Saud family, fearful of overthrow and unrest, granted the clergy more influence as part of an attempt to stave off the growing menace of Islamism, embodied by both the bloodshed at the Mecca mosque and Iran’s Islamic Revolution. Accordingly, MBS grew up with “rigid religious rules on society to ensure that its religious establishment didn’t turn on the royal family as the Iranian clerics had on the Shah of Iran,” House observes.

Like countless other young Saudis, MBS spent his formative years “chafing under the domination of religious rules and restrictions.” Music and movies were forbidden, with entertainment options limited to “grim-faced religious scholars with long beards reading the Quran” on TV.

The embrace of more strident brands of Islam had other fateful consequences. “While it preserved Al Saud rule, it helped spawn more radical Islamists in Saudi Arabia” and beyond. Fifteen Saudi hijackers helped perpetrate the Sept. 11, 2001, al Qaeda terrorist attacks, leaving thousands dead and initiating the Global War on Terrorism that lasts to this day. It was a disastrous policy, for both the world and Saudi Arabia.

Consequently, by the time that MBS was 20, U.S. intervention in the Middle East was at an all-time high, and Islamists threatened the stability of Saudi rule and the region itself. It also contributed to what many young Saudis call “the lost decades”—the period in which the kingdom was ruled by aging kings afraid of upsetting the apple cart and resistant to reform. The kingdom continued to rely on its petrodollars, with a workforce that was both economically and socially ill-prepared for the future.

By the time the elder Salman assumed the throne in 2015, the kingdom was on the verge of crisis. Oil prices had crashed to $44 a barrel from $108 six months earlier—the country’s reliance on oil was threatening its future. Indeed, half of the government’s budget went to pay salaries to a population that was almost completely dependent on government largesse. The budget, House observes, “was unsustainable.” And an exploding population of young Saudis, many unhappy with the lack of opportunity, loomed. Economically, the country needed to diversify. Socially, young Saudis needed to let off steam. In many respects, the social contract between the government and the governed needed to be rewritten. This is precisely what MBS has sought to do.

As the sixth son born to Prince Salman’s first wife, MBS’s ascension was unlikely. Yet his mother pushed him, instilling a deep competitiveness and drive. As House documents, he was willful from the start. In many respects, he is an archetype of his generation, with a love for, and appreciation of, both technology and forward-thinking that was largely absent in many of his more constrained predecessors.

Women’s rights have grown by leaps and bounds under MBS. The changes have been seismic and, House convincingly argues, largely underappreciated by the West. His plan for a brighter and more sustainable future, labeled Vision 2030, pledged, among other things, to enhance women’s “productive capabilities and enable them to strengthen their future.” In a mere six years, female participation in the labor force hit 37 percent in 2022—more than a 70-percent increase. Women are now ambassadors, heads of banks and major corporations, and have prominent positions in law firms. They can now drive, and segregation by sex, previously widespread, has eroded.

MBS has also prioritized diversifying the economy, with seemingly grandiose visions of the future. Some projects look promising, others less so. But the crown prince clearly recognizes that change is essential. And that change will have to be imposed from the top. Those who seek to stand in the way of his vision of progress will be cast aside—imprisoned, face house arrest, and, in some cases, disappeared. It is his way or the highway, and this is not a Western-style democracy—another fact that some in the West have failed to acknowledge.

As House observes, MBS recognizes the necessity of warming relations with Israel and continuing a security partnership with the United States. But this is not a man who feels constrained. He will—and has—reached out to Russia and China, too.

MBS is a man on a mission who has consistently chosen “bold, brutal, high-risk actions, always opting to act quickly because mistakes can be rectified.” He believes he is going to reshape the world and Saudi Arabia’s role in it. And that world, it is clear, will be reckoning with his rise for years to come. The United States and its allies would be wise to take note. For better or worse, such men make history.

The Man Who Would Be King: Mohammed Bin Salman and the Transformation of Saudi Arabia

by Karen Elliott House

Harper, 304 pp., $29.99

Sean Durns is a senior research analyst at the Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting and Analysis.