There are gamers, and then there are Sims players. The Electronic Arts life simulator, launched 25 years ago, is notorious for its eccentric fanbase. Players, most of whom are adults — married, employed, busy — spend evenings and weekends simulating the tedium of their real lives in a digital dollhouse. On Reddit, one reveals how she slowed down the in-game time so as to “give my Sims proper routines”; the mother in her Sim family “wakes up at 5am, does her skincare, makes breakfast for everyone… feeds the pets, gets dressed, does her makeup, sprays perfume, and wakes up and feeds her toddler child all before 8am”. For whatever reason, the drudgery of domestic labour becomes addictively fun when you’re compelling an automaton to do it.

Sims fans are not what laymen would expect gamers to be. The shouty young men who crack rape jokes in Call of Duty lobbies are nowhere to be found in Pleasantview. The fandom, unusually for gaming, skews about 80% female; the gameplay is less about gunning down insurgents than building homes and families, nurturing relationships and customising interior decor. The game gives players godlike control over their creations, allowing legions of highly skilled “modders” to tinker with bespoke elements. Its limitless customisation has attracted a sizeable and vocal LGBT constituency; some exclusively programme lesbians; others make almost all their Sims parents polygamous. Physicality and clothing is entirely unisex, fitting neatly into transgender philosophy; same-sex marriage was introduced to the game in 2009, six years before it was legalised in the US where the game was created.

The Sims is a Californian export, a strange flower from the hothouse of Silicon Valley in the Nineties. The game’s conceptual power was that it reflected the radical entrepreneurialism of that time, allowing players to pull up the roots of known institutions — the family, the town, life and death itself — and redesign everything to the whims of the individual. The Sims is one big lab experiment for different social and sexual dynamics, and even in marketing EA was careful to court progressive favour with Pride campaigns and tactical brand partnerships. Although the spectrum of gameplay is as varied as that of players themselves — some choose, as above, to simply rehearse traditional family roles by putting a mother through three hours of tedious housework before sunrise — both the format of the game and its ideological foundations are inherently liberal.

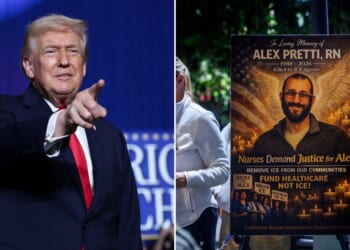

It’s hard to imagine a scenario more heartrending than grubby realpolitik clashing with this sunlit cyberworld. Unfortunately for Sims players, that’s exactly what happened: EA, the game’s Californian publisher, founded in 1982 by a former Apple employee called Trip Hawkins, has been acquired for a cool $55 billion by a consortium including none other than the Public Investment Fund of Saudi Arabia (run by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who the US not too long ago determined had personally ordered the assassination of journalist Jamal Khashoggi) and Affinity Partners — the Floridian investment firm founded by Jared Kushner, Ivanka Trump’s husband and an architect of the Gaza peace plan. A Gulf petrostate where homosexuality is punishable with decapitation, and a son of the Trump dynasty; you could not possibly cook up a less desirable cast of buyers for perhaps the most liberal gaming franchise in history.

“It’s hard to imagine a scenario more heartrending than grubby realpolitik clashing with this sunlit cyberworld.”

Predictably, the players are rattled; a boycott is underway. “It’s always disheartening as a queer woman and a disabled person seeing the places [where] I once found comfort and safety online shrink to a significantly smaller degree,” writes one. Many fret that LGBT content will be phased out of the game, distasteful to the Saudi stakeholders or plain old American conservatives in the Trump orbit. “Even if the Sims stays the same, I don’t want my money to go to those people,” writes another. “The series is very much dead to me after this.”

For some players, this is less about the selling-out of a favourite game than the loss of a better world. One put-out Prometheus, watching the gods snatch back fire, writes: “It’s not just a video game to so many of us; I’ve rebuilt Paris, New York, Barcelona… I can’t just abandon ship and start over, [after] 10 years of world building. I can’t support Saudis or Kushner. I guess I bought my last pack.”

It is difficult to think of a cultural product, game or otherwise, which so precisely captures the spirit of Western hyperprogressivism. The naive political philosophy of Millennials is perfectly mirrored in the dynamics of the simulated world: it is an exclusively digital, infinitely customisable reality which comes into being simply because I say it does. The basic facts of life — one’s intelligence, talents, physicality, even biological sex — are all mercifully tweakable within the game’s cyber utopia. Grinding moral forces like shame and disgust are reduced to minuscule “moodlets” which waft away in a few in-game hours. As in the ethos of Millennial liberalism there is no solid credo, just a shifting and conditional system of values geared towards gratification and experiment. Beyond the arbitrary goals of accruing wealth and building impressive houses each player ruthlessly pursues their own idea of satisfaction, sometimes through outrageous acts of sadism: the classic Sims experience is to put a character who displeases you into a swimming pool before deleting the ladder (I may be speaking from experience). Gamers often alternate between creating “good” and “evil” Sims, where the latter are simply agents of chaos sent to torment and exploit the other residents. The moral bent of gameplay tends to be black and white; it’s a world that suits players who see reality as such too. The system even shields players from mortality itself if they so choose. “When my first cat died, I brought her back to life”, writes one, who has since chosen to turn off the ageing feature altogether.

The Sims is a tabula rasa for building second, third, fourth lives or recreating reality as you believe it should be. Many players recreate family members; some recreate exes and torture them or simply keep them around for company, fabricating a resolved timeline of their own lives devoid of loss or rejection. The Sims is such a compelling and successful game because it fully actualises the desire to retreat into a dreamworld — but rather than the magical medieval land of Zelda or the pastoral cuteness of Stardew Valley, this dreamworld is of your own, almost limitless, making.

How strange, then, for this symbol of untethered idealism to come into contact with disturbing political realities. It is not just the idealism of fans thrown into disarray; The Sims is being thrown into confusion along with the American progressive optimism which created it as tech philosophy, and the country more broadly, lurches to the Right.

Like other experiments in tech utopianism, The Sims is still reliant on real-world capital and anchored to decidedly un-rad bad actors. I can sympathise with fans’ misery upon being rudely reminded that their paradise was a shadowplay all along; it must be quite a jolt suddenly to see the puppetmaster’s haggard face, his dirty fingernails. In a game centred around ultimate control, wresting power from the gamer god because of something as earthly as a business buyout exposes the illusion. EA has turned the big lights on.