Though we rightly celebrate the young volunteers who went South in the civil rights movement of the 1960s, most stayed only several months or perhaps a few years. Nowadays few remember the names of the small number who remained for the balance of their lives, like Charles Sherrod in southwest Georgia and Robert Mants in Lowndes County, Ala. Similarly, two decades later, someone could decide to become a community organizer on the Far South Side of Chicago before leaving after three years for Harvard Law School, a life in electoral politics, and a lazy retirement in multiple mansions.

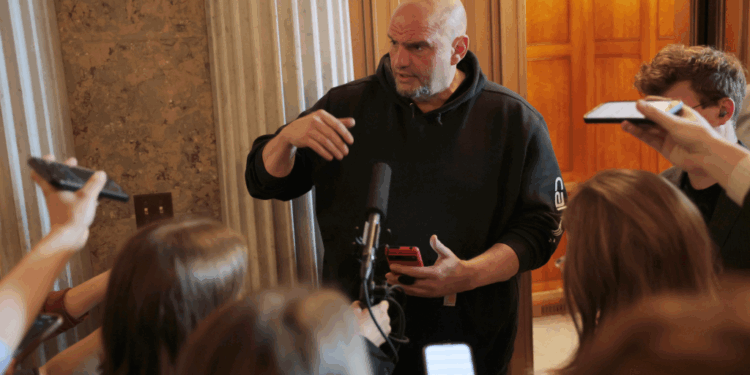

John Fetterman moved to Braddock, Pa., in the winter of 2000-01 at age 31 as a community youth worker, and now, 25 years later, still lives there. Like Sherrod and Mants, and unlike Barack Obama, Fetterman stayed.

Born to a very young couple, Fetterman suffered through “a lonely and awkward childhood” during which he was “routinely made fun of and bullied” on account of his unusual height—he’s now 6’8″—and prominent ears. He recalls being “friendless” and declares that “I have always had contempt for myself. I hated the way I looked,” he writes in his new memoir, Unfettered. Only tardy success in high school football mitigated his misery.

After college, Fetterman earned an MBA and won a dream job at a top insurance-industry firm. But feeling unfulfilled, he simply quit and after a bit of roaming ended up in Pittsburgh’s once-vibrant Hill District, working with black youth. He left to earn a master’s in public policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School before moving to Braddock, just southeast of Pittsburgh, again working with young people in “a ghost town” that had lost 90 percent of its population and now featured “shuttered storefront after shuttered storefront.” Echoing our 44th president, Fetterman writes, “I was intrigued by the idea of actually making change and trying to reverse years of abandonment.”

Family members viewed his move to Braddock as bizarre, but “I thought it was important to live in the community, among the students I was serving,” not in a Pittsburgh equivalent of Obama’s Hyde Park. Five years passed, during which “two of the young adults I worked with at the youth center” were killed. That motivated Fetterman to run for mayor, and after a 149 to 148 victory he took office in early 2006. A year later a young Brazilian-born woman sent him a letter after reading a magazine story about Braddock, and after an invitation to visit they married in 2008. They now have three children.

In 2016 Fetterman lost a Democratic primary run for the U.S. Senate, but becoming well known statewide allowed him to triumph in a 2018 race for lieutenant governor. That office’s most influential role is chairing the state Board of Pardons, which brought Fetterman into conflict with his more hesitant friend, state attorney general—and now governor—Josh Shapiro, whom Fetterman called a “fucking asshole” during one hot mic meeting. Now he magnanimously writes that Shapiro “is a credit to the state and may one day be a credit to the country,” “even if we no longer speak.”

Early in 2021 Fetterman launched a second run for the Senate, only to be immediately targeted by a New York Times hit piece focusing on a 2013 incident in which Fetterman had confronted a black Braddock jogger after hearing gun fire. The insinuation that Fetterman was a racist vigilante was far from subtle, although two other witnesses had also heard shots, and the jogger, although unarmed, would later be criminally convicted in a separate incident.

Amplified by two primary opponents, the Times’s accusation “marked the beginning of the critical depression and suicidal thoughts” that would peak after Fetterman in 2022 won both the Democratic nomination and then his fall race against Republican Mehmet Oz. Four days before the primary Fetterman had a stroke and underwent emergency surgery to remove a blood clot in his brain; on primary day itself he was again on an operating table, having “a pacemaker with a defibrillator” implanted in his heart. The stroke left him “effectively deaf,” but “I was not cognitively impaired.”

Fetterman’s hearing loss made for an excruciatingly difficult contest against Dr. Oz. “I made a private pact with myself that if my physical condition did not get any better” he would drop out, Fetterman writes, and “by the end of the summer I wished I had quit.” Opposition attack ads “were chipping away at my self-image,” since severe depression leaves you “always searching for a way to hate yourself.”

An October 25 debate against Oz was a disaster. “My nerves beat me down. I had wilted. I’d choked,” and in its wake “I had mentally collapsed.” Now “I never thought I would win” the race to become a senator, which felt all well and good since “I didn’t deserve to be one.” But win Fetterman did, by a margin of more than 250,000 votes, yet that evening he felt “no joy. No sense of accomplishment,” and the next morning “I stayed in bed as long as I could,” since his bed “had become my only safe harbor.” Wife Gisele knew that John had had “a nervous breakdown,” but since “I was a stubborn asshole,” Fetterman refused to seek treatment.

“I returned to bed and largely stayed there for the rest of November and through December, until I was sworn into the Senate in early January,” Fetterman confesses. “I dreaded the light coming up in the morning. I stayed in bed as long as I could, then moved to the couch, where I spent hours staring out the window.” His younger brother Gregg realized John was “just despondent, just truly broken,” and remained unwilling to seek help.

Finally, in late February, Fetterman was admitted to D.C.’s Walter Reed Hospital, where he remained in the Traumatic Brain Injury Unit for more than 40 days. “I will always be in recovery, both from depression and the stroke,” with moderate permanent hearing loss and dependent upon his pacemaker to ensure his continuing heartbeat.

To call Unfettered robustly and indeed relentlessly self-critical risks understatement. “I am not collegial, and as a senator, you need to be to get anything real done,” Fetterman admits, although he has bonded with young Alabama Republican Katie Britt and Vermont Democrat Peter Welch, who is older than Fetterman’s dad.

Fetterman’s fervent support for democratic, multiethnic Israel has earned him intense hostility from faux progressives whose anti-Zionism often barely cloaks their latent anti-Semitism, but Unfettered offers no apologies. “I don’t take positions for my own self-interest. I take positions based on what I believe is right. I know this has cost me support from a significant part of my base, and I’m well aware that it may cost me my seat” if he chooses to run for reelection in 2028. “I’m completely at peace with that.”

His admission of poor collegiality notwithstanding, Unfettered makes clear the senator’s political astuteness. “I’m not sure anyone knows what the Democratic Party is anymore,” Fetterman writes. “We need to get away from the progressive and liberal notion that everything the Democrats do is right and above reproach and everything the Republicans do is wrong and evil.” He adds that the Democratic Party has “lost the support of the regular Joes who were once its backbone” but who now often vote Republican, because “to the regular Joes, Trump exemplified strength.” And in a final insight that its subject should take to heart, Fetterman observes that “Trump could be less polarizing and more collaborative if his public persona were more like his private one.”

Unfettered recounts a hugely compelling life story, one that is at times deeply traumatic but also utterly humble. “I still live in a forgotten America,” Fetterman concludes, but all of America has no more absolutely authentic an elected official than John Fetterman.

Unfettered

by John Fetterman

Crown, 213 pp., $32

David J. Garrow’s books include the Pulitzer Prize-winning Martin Luther King Jr. biography Bearing the Cross and Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama.