President Donald Trump created new tariffs on April 2, a day he would come to call the Liberation Day. In July, he decided to increase tariff rates. On November 20, the same decided to pull 10 percent of the tariff he had imposed on Brazilian goods entering the US economy, leaving the rate at 40 percent. Brazil is the greatest coffee producer and exporter in the world, and its coffee used to represent one-third of what the United States of America consumed. With the tariffs imposed in April, prices rose rapidly and consumers in the US felt unsatisfied with the quality of product they had been getting, and—in case they wanted the same type of coffee they had been getting before Liberation Day—they would have to pay more for the same. Only because Trump used his “personal power,” the definition given by Ryan Zinke when talking about tariffs in the eyes of presidents, “Congress does not get a say as to which tariff is approved or not, and yet presidents make use of this because it shows their willingness to save the economy.” What is crucial for the understanding of the concept of tariffs is that, by applying them, a president is not saving anybody. In reality, the ones paying for the tariffs are the consumers inside the nation.

President Trump announced the tariffs aiming at two goals: protecting American producers and the relocation of foreign companies to the US. Some might argue that he did protect American producers, but at what cost? The imposition of tariffs does not mean that consumers will magically change their taste as far as what they like to eat or drink, it only means that consumers have to adapt to the new prices, which in reality will keep them from spending money that they otherwise would, slowing economic growth.

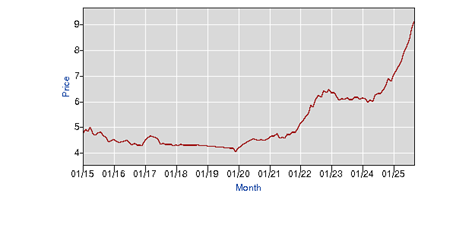

To some extent, President Trump understood that these measures were not beneficial to his economy and that is why he pulled part of them. I imagine he had a realization moment when someone explained to him that his people were the ones paying for his tariffs, again keeping them from spending their money in other ways. Brazilian coffee producers expected a greater decrease in the tariffs rate. In reality, a renowned Brazilian newspaper, points out that: “Some sections of Brazilian agro expected tariffs to be completely pulled and set to zero.” In another article published on the same matter, coffee prices have increased about 40 percent for American consumers since the tariffs were first imposed, which can be viewed in the following graph:

(US Bureau of Labor Statics – Coffee Prices over period of time)

During the last summer, I spent back home in Brazil. I had several relatives ask me how the tariffs had affected the prices of goods on shelves in grocery stores, and I didn’t know what to answer them other than: “It’s bad.” It was noticeable that prices were rising more than expected in such a short period of time, and I didn’t really understand why. After learning more about economic concepts and the insights of the Austrian School, I had a better grasp of what happened and why tariffs were imposed. If I could go back and answer my relatives’ question again I would explain: “I believe that we can all have an idea that tariffs don’t benefit a nation’s economy now that we’ve seen what it did to prices in the US. It is clear that the prices rose, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that the product gained value, which is proven by the Brazilian coffee producers reactions to the tariffs not being completely cut. Consumers are paying for the price of the tariffs along with producers that have had their sales go down and can’t do business with Americans as much as they wish.” Tariffs keep mutually-beneficial trades from happening because part of the capital being used to negotiate is not going to either of the parties, it goes to the government. And, as Frédéric Bastiat describes government in The Law: “law and force keep a person within the bounds of justice, they impose nothing but a mere negation. They oblige him only to abstain from harming others.” The government should only keep people from harming others, and not disallow mutually-beneficial exchanges that harm no one.