When we think of modernist art, a stern biblical phrase like “Lord God of Heaven” is not what comes to mind. Yet an argument could be made that literary modernism kicks off with just those words, at the head of this archaic stanza:

Lord God of heaven that with mercy dight

Th’ alternate prayer wheel of the night and the light

Eternal hath to thee, and in whose sight

Our days as rain drops in the sea surge fall…

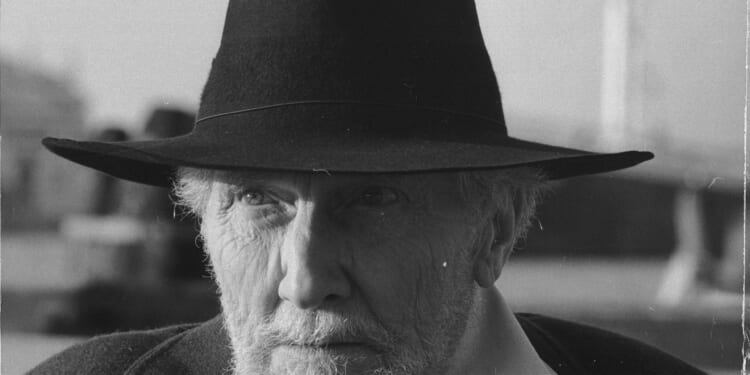

This is the first stanza in Ezra Pound’s first book of poems, A Lume Spento (“With Tapers Quenched”), which came out with a Venetian publishing house in July 1908. There will be more on what these lines mean in just a moment. It is worth noting beforehand that Pound’s second book, A Quinzaine for this Yule — a willfully obscure title — was published in London in December of the same year. It is a yuletide collection, a sort of avant-garde Christmas album. And it is striking to see Pound, enfant terrible of modernist poetry, open this second book with a prayer in the language of medieval romantic poetry. “O God”, he writes, “purify our hearts!” (O Dieu, purifiez nos coeurs!). Clearly, being a modernist does not rule out talking to God.

With this in mind, we come back to the first stanza of Pound’s debut. He is praying, here, to a deity clothed in love and compassion (“with mercy dight”). The image Pound creates in this short poem is a beautiful one, though he makes us work for it. His language is rebelliously outdated. In these early books, Pound is making himself a modernist by studiously refusing to write in a disillusioned 20th-century idiom. And he wants us to know that the “Lord God of Heaven” is the one in whose eyes all “our days” quickly fall, bright and translucent, “as rain drops in the sea”. All human urges and passions and acts are, to God, just “drops that dream and gleam and falling catch the sun”. They die, or we die, when we reach the vast undying sea. And our only life is to catch God’s light as we fall. Pound wants his own poems to be like that, he tells us. He wants his stanzas to dazzle like sunlit rain. Like “mirrors”, he says, “every opal one”. Mirrors that flash with sky.

And this brings us, unexpectedly, back to Christmas. Pound returns to this image of life, literature, and God in a fragmentary poem that appears in his second book, A Quinzaine for this Yule. (With “quinzaine”, he is referring both to the fact that the book contains 15 poems, and that they offer a set of 15 quasi-liturgical readings at Christmastide.) Here, Pound finds something of the “magic of past time” in the image of a “sun-smit sea”. He now compares human life to sea spray. The “sea deep of the whole man-soul”, he claims, is somehow held within a single droplet. The whole “space” of any “individual being” is just a touch of “opal spray” that shoots up from the boundless deep. Each droplet only exists and catches the light of the world — and of God — because, for an instant, it is “going heavenward”.

Is there any real connection to Christmas, though? Or is this just a random image that Pound chose to include in his December 1908 book, after introducing it in July of the same year? Let’s see.

God reappears in Pound’s December poem — but at the end of the poem, now. In A Quinzaine for this Yule, Pound tells us where the “opal spray” of all human history ends: it falls into “the great whole liquid jewel of God’s truth”. What a line. Pound’s poetry is full of such gorgeousness. He seems to be at his best when writing about “the waters”, and it is fitting that he decides to call God, in his December book, the “God of waters”.

But again, we could ask: what does “the great whole liquid jewel of God’s truth” have to do with Christmas? And what does Christmas have to do with what Pound calls the “magic” of time? To begin with, Pound tells us in his Christmas book that he had a sort of vision of the Virgin Mary on the canals of Venice. Her presence there is one reason why God is, for him, the “God of waters”. And this is what Pound says, blending the medieval prayer we’ve already seen (“Purify our hearts!”) and a couple of biblical passages:

O God…

Purifiez nos coeurs

For we have seen

The glory of the shadow of the

likeness of thine handmaid…

As none of Pound’s original readers would have missed (but many will today), he is echoing here the words of Mary’s song, the Magnificat, which Christians traditionally read in December. In her song, Mary blesses the Lord for being mindful of “the lowliness of his handmaiden”. The scandalously pregnant girl then makes a prophecy, one that has, incredibly, come true: “All generations shall call me blessed.” Pound himself blesses her, calling her in one early poem the “Virgin Mother”. His youthful reverence for Mary is something that connects him to the 19th-century Romantics: Jesus’ mother has a special place in Romantic art and culture that we do not yet fully understand.

But Mary is not the only sacred figure who appears “upon the shadow of the waters” in the pages of Pound’s Christmas book. He recalls, too, how Mary’s son once walked “upon the wave” in Galilee. The scene Pound has in mind is narrated in several of the Gospels. This is how it is told in the Gospel of Mark:

“About the fourth watch of the night Jesus came to the twelve disciples, walking on the sea. He meant to pass by them, but when they saw him walking on the sea they thought it was a ghost, and cried out; for they all saw him, and were terrified. But immediately Jesus spoke to them and said, ‘Take heart, it is I; have no fear.’ And he got into the boat with them and the wind ceased. And they were utterly astounded.”

Pound reworks this scene in A Quinzaine for this Yule. Though Jesus had seemed to be “some uncertain ghost” hovering on the Sea of Galilee, he tells his friends (in Pound’s words): “I am no spirit. Fear not me!” In a bold move, the poet then identifies himself and us, his modern readers, with “the twelve storm-tossed” that night in Galilee. And how does Pound make this identification between us and Jesus’ original disciples? “We bewildered”, he writes, “yet have trust in thee”. We, too, have somehow seen the son of Mary stride “upon the wave” in the lines of Pound’s poetry.

Now, I realise that a young bohemian glimpsing the figure of Mary one night as he is wandering through the “Venice of dreams”, and then vaguely evoking the “holier mystery” of Jesus himself walking — not as a ghost, but a “God-man” — on some ancient inland sea, might not seem to have much to do with a modern Christmas. But modernists want us to work for it, and the Gospel-writers, too, want us to work for it. And there is something here for us to work towards.

We have already seen that Pound is attached to the image of history as a rain or “opal spray” on the surface of what we might call the “world-sea”. We are nothing, for him, but “drops that dream and gleam” in God’s light. We only exist as we fly skywards and then fall seawards. But with the one that Pound dubs the “God of waters”, there seems to be a further possibility. For both Jesus and his mother are figures that emerge from the world-sea. They are not just, like us, drops of rain or sea. And in the case of Mary’s son, Jesus, he is a figure who can walk — as a real man, not a phantom — on the world-sea.

And isn’t this what Christmas ultimately is? A celebration of the mystery — consciously or not, believingly or not — that “the great whole liquid jewel of God’s truth” once joined the “opal spray” of humanity in the person of Jesus? That the deep and unconditioned truth of the sea joined the evanescent condition of the spray, through the virgin-motherhood of Mary? That the magic of all time passed, somehow, through the magic of their time? And that the magic of their time still passes, somehow, through the grim magic of ours?

If all this seems too mystical or too occult for prewar avant-garde art — I assure you it is not. We are just far less mystical than the modernists. Pound makes no secret of his own eerie identification with Christ, or Christus as he calls him. He writes this in A Quinzaine for this Yule:

…in midmost us there glows a sphere

Translucent, molten gold, that is the “I”

And into this some form projects itself:

Christus…

A once-devout son of the Presbyterian Church, Pound has ceased to be a believer. Yet the “translucent” form of the ego that he envisions here is not one that merely flicks and falls like spray on the world-sea. Even the shallow modern self is a “sphere” that the form of Christ can somehow inhabit. In a heterodox sense (and Pound notes, here, that he is not orthodox), he still believes that Christ can live in us.

As Pound hints, Christmas is a time to remember that within us all “there glows a sphere” where Christ can live. This is a possibility, mystic or artistic, that avant-gardists were still able to celebrate in print in London and Venice circa 1910. If it seems bizarre to us now, it is only because so much cultural and spiritual ground has been lost.

For us, today, modernism is nothing more than a subversive mood in the early days of the 20th century, a youthful drive to create post-Victorian forms of expression — free verse and so on. Pound’s one-line manifesto, “Make it new”, seems to us to say it all. But we don’t even get the motto right, much less, the deeper modernist imperative.

“Pound’s one-line manifesto, ‘Make it new’, seems to us to say it all. But we don’t even get the motto right, much less, the deeper modernist imperative.”

Significantly, “Make it new” is extremely old. Pound lifted the line, in a somewhat convoluted way, from ancient texts that touch on the origins of China’s Shang dynasty. In a couple of these texts, one virtuous monarch of the 18th century BC is said to have engraved the words “Renovate, renovate!” on his washbasin. Pound then put his own translation of the Shang-dynasty dictum — “Make it new” — into circulation in the 20th century AD.

But what does this dictum mean? Pound tells us, in one remarkable poem in A Quinzaine for this Yule, that Making it new means, among other things, “giving to prayer new language”. Notice the phrasing here: giving to prayer new language, not ceasing to pray altogether.

We could surely say of Christmas, too, or yule as Pound calls it, in a Gothic vein, that we must make it new. Its truth and freshness, its imagistic light, is not simply there in the world. It is something that we must bring to the world, again and again. (Curiously, in one Gospel, Jesus says: “I am the light of the world”; in another he says, “You are the light of the world”.) Read correctly, then, modernism’s “Make it new” is in conflict with late modernism’s tendency to blur and suppress the mystical, even dogmatic, elements of our ancestral feasts. Read correctly, “Make it new” means: Celebrate the yule.

This becomes perfectly clear once we remember that modernism doesn’t just have one call to arms: “Make it new”. There are, in fact, two versions of that saying in Pound’s writings, and the earlier one is entirely his own. It is not a translation. Precisely in the years when Pound was compiling his first books of poetry, his motto read this way: “Make-strong old dreams lest this our world lose heart.” The italics are his.

And that is the task, and the beauty, every Christmas. If we want there to be “peace on earth, good will toward men”, we must make-strong old dreams. If we want there to be “glory to God in the highest”, we must make-strong old dreams. And in cities like London and Venice, in Pound’s day and ours, Christmas is the oldest and brightest recurring dream of all.