The Bureau of Labor Statistics released new December employment numbers last week, showing another month of disappointing job growth and a labor market moving sideways. According to the report, the unemployment level fell slightly from 4.5 to 4.4 percent, month over month, but the number of unemployed people rose by 225,000, the second-highest increase in more than a year.

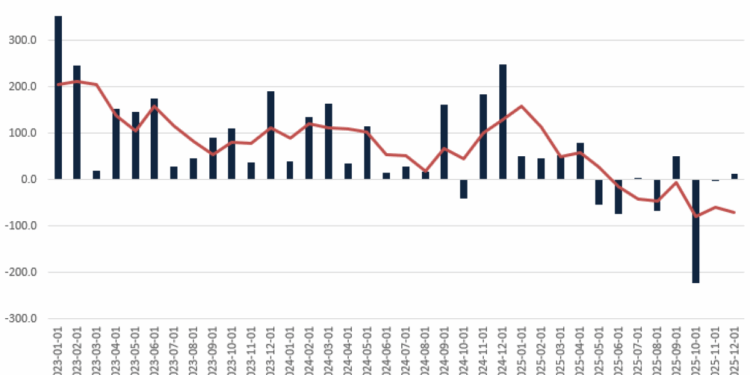

Payroll employment showed another lackluster month of growth, with the job market adding 50,000 payroll jobs. Payroll employment was also revised down significantly for October and November:

The change in total nonfarm payroll employment for October was revised down by 68,000, from -105,000 to -173,000, and the change for November was revised down by 8,000, from +64,000 to +56,000. With these revisions, employment in October and November combined is 76,000 lower than previously reported.

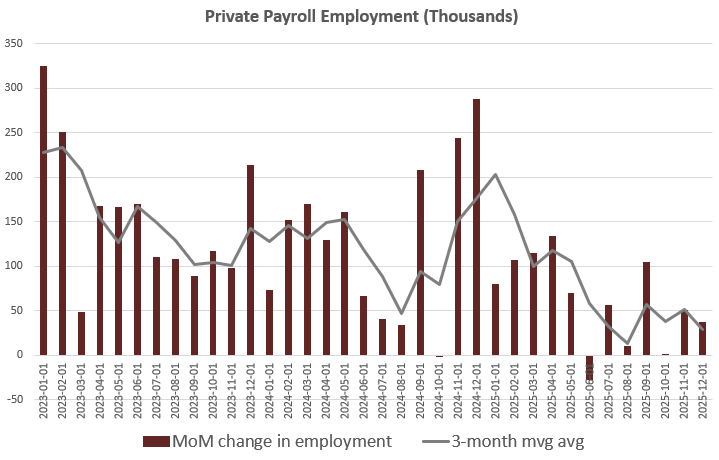

As a result, the average number of jobs added per month over the past year was only 48,000. That’s less than a third of average monthly job growth reported during the previous year. Some of that decline can be explained by a drop in government employment, but private-sector jobs are falling off as well. For example, in December, private payroll employment was up by 37,000, making the average private job gain over the past year 61,000 per month. That’s less than half of the average from the previous year. Moreover, if we look at the three-month moving average in private job gains, we see that the total has collapsed since April of 2025:

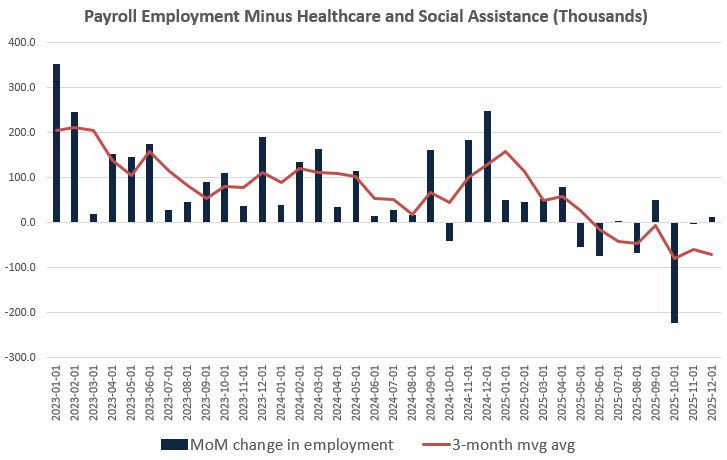

When we dig further into the numbers we find that overall jobs numbers have been significantly buoyed by employment in the “healthcare and social assistance” categories. In fact, if we look at total payrolls minus healthcare and social assistance, we find that job growth has actually been negative during three of the past six months. Moreover, by this measure, the three-month moving average has been negative since June of 2025.

But why should be care about this particular category of employment? If we’re trying to get a sense of where the economy is in the current business cycle, we want to avoid employment sectors that are largely immune from cyclical changes, especially if that immunity comes from tax-funded subsidies. Subsidized industries tend to not reflect economic changes nearly as much as other industries. After all, they’re functioning largely outside the real marketplace.

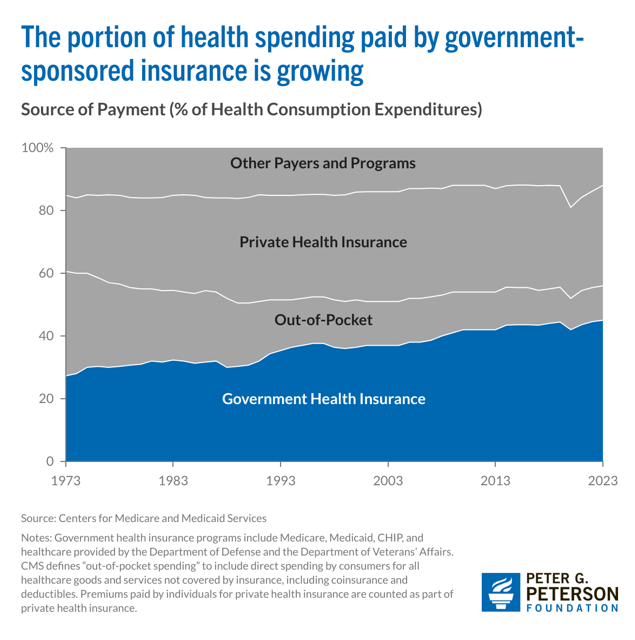

This is the case with healthcare and social assistance since both areas rely heavily on government grants and programs. Healthcare has been one of the fastest growing areas of federal spending over the past decade, and now nearly half of the entire sector is now government funded.

Government spending was 45 percent of the sector in 2023 and it has only grown since then. Moreover, social assistance jobs—which the BLS notes overlap considerably with health care—are heavily subsidized by Medicare and are largely a subsidized industry.

So, if we remove those jobs to get a better sense of where the real, private job market is, we find mostly negative job growth.

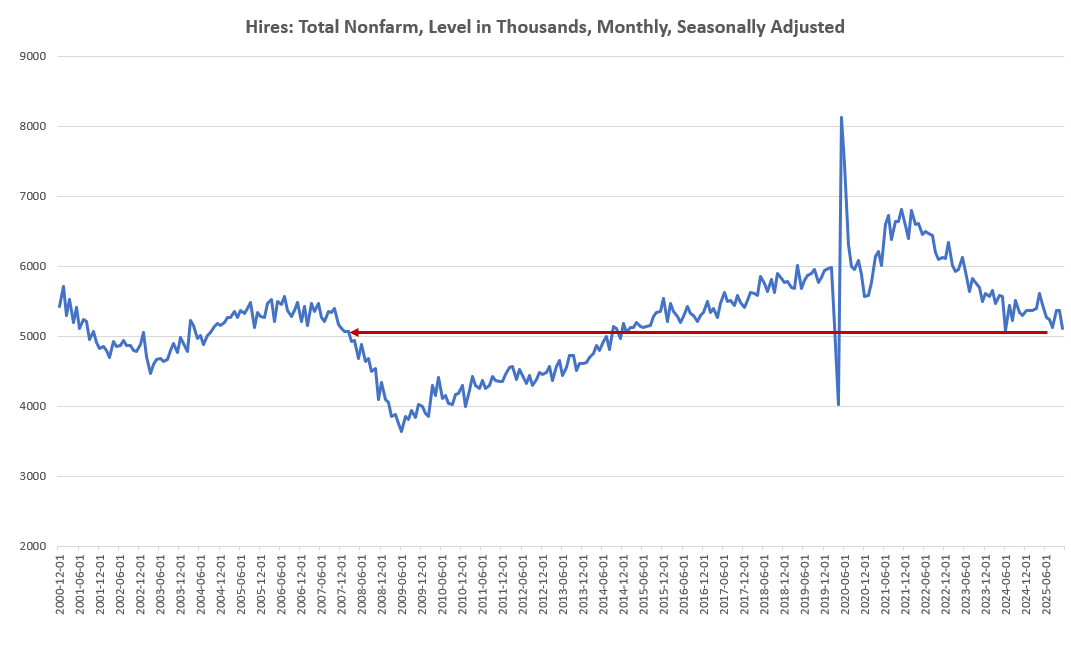

This is not surprising when we consider that total hires in the economy have fallen back to where they were in December 2007, at the beginning of the Great Recession. Even the Fed has admitted we are in a no-hire-no-fire economy in which there is not yet a wave of layoffs, but few employers are hiring. This means younger workers entering the work force are encountering few job openings.

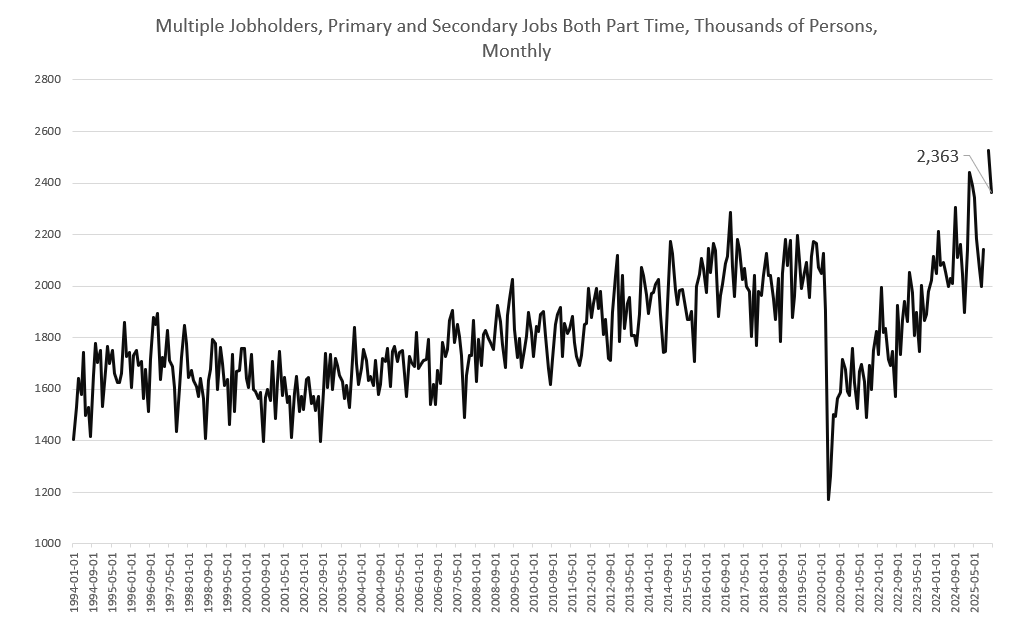

Similarly, obtaining full-time work continues to be a challenge for many. For example, totals in multiple job holders have reached new 30-year highs in recent months. In cases where multiple jobholders have two part time jobs, the total is now 2.3 million, near November 2025’s 30-year high of 2.5 million.

More workers are needing to resort to part time work to pay the bills, and the shortage of job offers appears to be impacting younger workers the most. For example, the New York Fed’s Dec 17 report in employment showed that the unemployment rate for “recent college graduates” (aged 22-27) is more than a point and a half higher than the overall employment rate. Workers aged 22-27 overall fared even worse, with an unemployment rate of 7.1 percent in September 2025, the most recent measure available.

This likely reflects the ongoing bifurcation in the economy that we continue to see. Older, wealthier workers and consumers drive ever larger portions of the economy and of spending, while younger and lower-income workers continue to earn less and spend less.

For example, a recent analysis from the Financial Times showed that the top 10 percent of consumers by income now account for nearly fifty percent of all consumer spending. This is up by more than ten percentage points over the past thirty years. Meanwhile, the bottom 80 percent of consumers now account for less than 40 percent of all consumer spending.