Earlier this week, a group of Syrian Arab men took hammers to a statue of a female fighter in the northern city of Tabqah. The statue had been erected relatively recently by the Syrian Democratic Forces (the SDF), the Kurdish-led coalition who expelled Isis from its former heartlands between 2015 and 2019 and governed had vast area of north-east Syria as an autonomous region ever since.

The warrior stood as a symbol of the fight against Isis’s murderous extremism — and the Kurdish political movement’s long-cherished dream of a devolved, federal Syria. Back in 2012, two million long-marginalised Syrian Kurds thought their fortunes had been transformed. The Syrian revolution enabled them to declare de facto autonomy in isolated “cantons” along the northern border with Turkey. Their bitter conflicts with Isis won them international military support from the US-led, UK-backed International Coalition to Defeat ISIS. Kurdish forces duly expanded out of the Syrian Kurdish heartlands known as “Rojava” and came to govern a region the size of Lebanon on a secular, feminist, and nominally direct-democratic basis.

The Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (to give it its official title) stretched from the Iraqi and Turkish borders to the River Euphrates. It retained its autonomy for well over a decade, keeping hold of Syria’s oil fields, plus tens of thousands of captured Isis members and affiliates. It even withstood the blitzkrieg offensive led by the militant Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) which led to the end of the regime of Bashar al-Assad in 2024.

The fallen female warrior now represents the defeat of that dream. Syria’s 14-year-old civil war has now entered its final, deadly phase — and the tentative Kurdish vision of a secular, federal Syria is finally being extinguished.

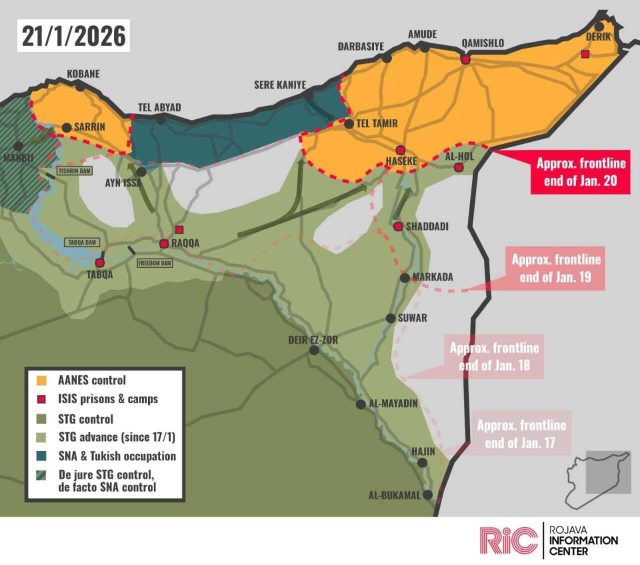

Across two January weeks, government troops, Islamist militias, and tribal forces under Syria’s new President Ahmed al-Sharaa, have begun to reclaim the territory, benefitting from mass defections of Arabs in the region who are deeply dissatisfied with Kurdish rule. The deadly conflict has now reached the gates of the Kurdish towns and cities strung along the border where the embattled Kurds are now primed to fight.

In Qamishli — now the de facto Syrian Kurdish capital — I speak to Gharib Hasso, the co-chair of the Kurds’ leading political party. “We see dialogue for national unity as essential,” he says. “If there is such an approach, and our rights are guaranteed, we’re ready.” However, the AK-47 in his hands demonstrates his willingness to continue politics by other means. “But if not, we will struggle. We’ll defend our land.”

Across the past fortnight, President al-Sharaa has reached a number of ceasefire agreements with the commander-in-chief of the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), only to use each one as cover to continue the advance into the Arab interior. During this time, the Kurdish forces have relinquished control of the Isis detention centres and camps they long administered on behalf of their UK and US allies.

The diplomatic and security chaos is now matched by the turmoil on the ground. In Qamishli, neighbourhood self-defence committees are handing out AK-47s and digging trenches at the entrance to Kurdish neighbourhoods. Kurdish fighters ride through the streets on top of BearCat vehicles provided by the US. They swerve around cars packed with ordinary citizens — old and young, male and female — waving weapons, SDF flags, and the peace sign associated with the Kurdish struggle.

At the Kurdish Red Crescent hospital in Qamishli, I see a man bang on the desk, demanding to be allowed to donate blood even though the blood-bank is at capacity. Bread is in short supply too amid mass power and water outages following the Syrian government forces’ capture of the region’s key energy structures.

Meanwhile, internally displaced Kurds from the regions occupied by al-Sharaa’s forces are arriving in these embattled enclaves en masse to seek shelter. Many have been driven from their homes for the fourth or fifth time since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war — and many express bitterness at al-Sharaa’s persistent breaking of ceasefires. “When they sat down and made [the first] agreement we were delighted, because we thought we would return home,” says Nisreen Mihammed, an elderly woman sheltering in a windowless school room with old Kurdish lessons still scrawled on the blackboard. “We were surrendering land to them, but then they attacked us… The bullets were flying and we had to run.”

“President Al-Sharaa may be an Islamist authoritarian — but he’s the kind of authoritarian who is open to Western investment.”

She and her fellow internally displaced Kurds are the victims of Trumpian realpolitik — and what Kurdish politicians and civilians perceive as yet another Western betrayal of their cause. The highly successful partnership to counter Isis, forged between Syrian Kurdish forces, the UK, USA and other members of the International Coalition to Defeat ISIS, appears to have run its course. With Assad defeated, the US has now thrown its weight behind his replacement. Al-Sharaa may be an Islamist authoritarian — but he’s the kind of authoritarian who is open to Western investment and a détente with Israel on his southern border.

Ordinary locals are outraged at the spectacle of US generals and Donald Trump breaking bread with their new president. Before al-Sharaa seized control of Damascus in 2024, he was the head of the al-Qaeda splinter group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham with a $10 million US bounty on his head. Now he is reportedly agreeing to align with the US against Iran and the prospect of a Western-aligned strongman opening Damascus up to business seems to have proved irresistible to the White House.

Still, what will become of the 9,000 or so Isis militants held in detention centres across north-east Syria remains to be seen. Scores have already escaped from one key detention centre held by al-Sharaa’s Islamist forces. Escapes have also been reported at the Al-Hol Camp, which holds around 20,000 Isis-linked women and children — here, the arriving government forces were greeted by scenes of wild jubilation. At another prison in the former Isis capital of Raqqa, Kurdish guards have been encircled and fired upon by Syrian government forces.

Al-Sharaa has apparently persuaded Trump that he is ready and willing to secure these facilities — and he can point to a track record of violently liquidating other militant factions en route to securing national power. Still, security analysts warn that for all that al-Sharaa’s Hayat Tahrir al-Sham party has attempted to rebrand itself as a stabilising force, its origins as an al-Qaeda splinter group together with its accommodation of Islamist extremists mean we shouldn’t take their promises at face value.

The ceasefire deal announced yesterday will see the Kurdish administration reduced to small enclaves within the region’s Kurdish-majority cities and villages, amid full-scale military and political integration within the central Syrian state. However, Kurdish trust in the regime currently stands at precisely zero — thanks to violations against Kurdish civilians and captured female fighters during the last offensive, and a longer-term track record of abuses of the Kurds and other minorities by government-allied militias.

With an overnight drone strike and motorbike bomb in Qamishli, and the Syrian government-allied militias reportedly advancing further upon the encircled city of Kobane, Kurdish politicians are meanwhile urging locals to join the mass mobilisation. “We’re with our people, for as long as there’s a drop of blood in our bodies,” says a young Kurdish fighter in front of a burning oil-drum. “We’re going to protect our people and protect our neighbourhoods.”

I watch protesters on both sides of the Turkey-Syria border attempt to storm the crossing, drawing live fire from guards. Even the mosques are blaring Kurdish revolutionary music, in a sign of the increasingly radical split between the country’s Kurdish and Arab populations — both Sunni Muslim.

In 2025, Islamist forces allied with al-Sharaa killed over 1,400 members of the Alawite community, who were perceived to be linked with the ousted president Bashar al-Assad — as well as hundreds of members of the Druze religious minority. A further conflict with the well-armed, highly-disciplined Kurdish forces would likely be far more deadly.

The Kurdish politician Hasso asks: “If those criminal militias… want brotherhood, why did they attack the Druze? Why did they attack the Alawites? Why do they attack the Kurds?” Even if the ceasefire deal is implemented, it’s unclear how the government’s forces will be prevented from further bloody violations aimed at totally liquidating Kurdish autonomy in the coming months.

This conflict is also about competing political visions. The Kurdish polity’s vision of a decentralised Syria granting devolved rights to local communities, municipalities and minorities was always met with suspicion by the Arab population of Rojava. The ongoing Isis insurgency drove the Kurdish administration to impose harsh security measures and significant political restrictions — which went against the grain of their stated vision of a free, democratic Syria.

Indeed, it was the defection of the Arab majority away from the formerly multi-ethnic SDF that led to the collapse of Kurdish rule. Kurdish fighters and civilians often refer to these uprisings as “Isis sleeper cells”. However, there are often legitimate Arab grievances mixed in: resistance to heavy-handed Kurdish rule; tribal opportunism; simple war fatigue; and a desire to live in a unitary, internationally-recognised state. Most Arabs never saw the federal project as anything other than a smokescreen for Kurdish nationalism. Those who toppled the statue of the female fighter were likely unaware it depicted an Arab, not a Kurd, slain by the terror group.

Still, the long, sad story of the conflict in Syrian Kurdistan is more complex than one of Arabs versus Kurds. In the Red Crescent hospital, I meet Aqid, 20, one of several Arab fighters who was injured fighting with his Kurdish allies against government forces along the Euphrates. “I don’t see any difference between Kurds and Arabs, we’re all one in the SDF,” he insists. “We all fight to defend our land and the honour of our people.”

Had it been implemented under less strenuous conditions, the Kurdish vision of decentralised, local autonomy could have been appealing to poor Arab regions themselves long economically excluded and politically marginalised by the centralised Syrian state. Hasso insists that the current war is an attack on this bold political vision of equitable governance for all. “This brotherhood that we’re building up, through which we’re developing our society — they want to destroy it.”

The Kurdish-led administration at least offered an alternative vision for a nation that has been dominated for decades by criminal militias. With the rapid collapse of the Kurdish-led governance project, a chapter has closed. Local friends now laugh bitterly at the mention of a “brotherhood of peoples”. The collapse of the Damascus-Kurdish ceasefire was met with scenes of wild celebration, as caravans of locals took to the streets, waving Kurdish flags, briefly jubilant at the opportunity to stand and fight.

The question now is whether the slender rights won in the course of this struggle can be preserved in these isolated Kurdish regions — as Kurdish forces fight government to a bloody standstill in their remaining cities. Syria’s recent history is rapidly running away from the dream of pan-Syrian multi-ethnic federalism. The Kurds are retreating back to the embattled enclaves from which they first launched their wars against Isis. Time seems likely to keep running backward.