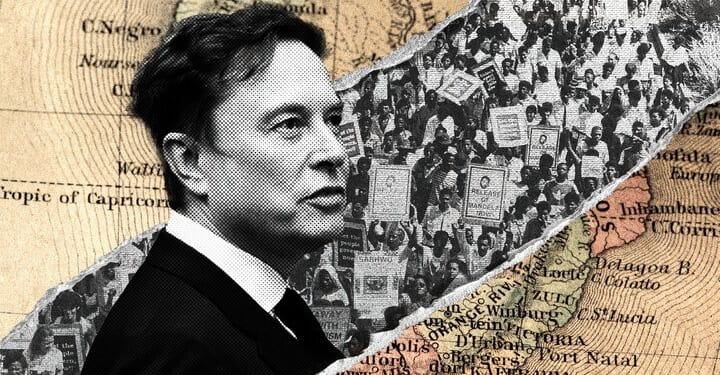

Elon Musk’s X feed has taken on a dark tone in recent months. Between posts promoting his companies and showcasing new AI tools, he seems to be anticipating — and sometimes promoting — a race war. Over the past several weeks, the world’s richest man has repeatedly suggested that the United States is on a trajectory toward violent racial upheaval.

He has “reposted” or approvingly quoted posts claiming that South Africa is our future; that the United States is at risk of turning into a “Global Favela”; that the Left is “import[ing] a new voting block from the Third World”; that “all other [racial] groups show extreme in-group preference and particular hatred for white people”; and that New York Mayor Zohran Mamdani seeks to “eradicate white people”.

The agents of collapse are unassimilated immigrants, aggrieved black Americans, and progressive elites who have inflamed resentment through years of identity-based moralising. The implied endpoint is civil conflict, for which he wants whites to prepare themselves.

These claims would be alarming coming from anyone. From a man of Musk’s unparalleled resources and influence, they warrant loud and unambiguous rejection. The hundreds of thousands of likes and millions of impressions garnered by Musk’s posts suggest that his views are shared by more than a few others. Despite flashpoints over immigration and high crime in a handful of American cities, the conditions in the country are generally peaceful. The streets are generally safe. The crime spike we endured in 2020 has fallen off. So why has “the race war is coming” proven to be such an attractive rallying cry?

I thought I had an answer. In my inaugural essay for UnHerd, I offered a short genealogy of our present political moment. I argued that President Trump’s rise had been abetted by a backlash against progressive overreach, especially on matters of race, and I expressed concern that the reactionary energy unleashed in 2016 — and again more intensely in 2024 — would culminate in a repudiation not only of racial politics, but of blackness itself.

But the “backlash” frame, while not inaccurate, isn’t what is most important about the present moment. It captures the direction of political motion but misstates its mechanism.

Backlash suggests something like a political analogue to Newton’s third law of motion: progressive excess produces an equal and opposite reaction; grievance is answered by grievance; and if the reaction takes on a racial coloration, that is only because the initial action was racially tinged. In this view, Trump’s return appears as a kind of inevitability — an elastic band released after being stretched too far. But this way of thinking drains politics of agency. Human beings are not rubber bands. They choose, within limits, how to respond to strain. Those limits are shaped by politicians, institutions, and the culture at large. These organise raw dissatisfaction into strains of discourse, thought, and belief, with varying degrees of coherence.

The Right’s response to progressive identity politics has not chiefly taken the form of repudiation. It has taken the form of adoption. A focus on racial identity remains the coin of the political realm. What we are witnessing is not merely a backlash. It’s a convergence.

For years, identity politics was treated — rightly — as a pathology of the Left. It displaced the individual as the bearer of moral and political claims, and instead proposed group membership, defined by race, gender, and sexuality, o as the proper grounds for justice. Classical liberals warned that once politics was organised around groups rather than persons, the state would become an arena of zero-sum contestation among identities, with predictable consequences for social cohesion. During the “racial reckoning” of the late 2010s and early 2020s, we saw enough of that dynamic to last a lifetime.

Yet in the months since Trump’s return to office, it has become clear that identity politics has not been defeated. It has just been rebranded. An insurgent movement on the Right has concluded, quietly but unmistakably, that identity politics is not a moral error so much as it is a powerful political technology. As a democratic ideal, it is corrosive. As a tool of mobilisation, it is extraordinarily effective. What I had previously described as backlash (against overly aggressive anti-racism) now looks more like a realisation: the right has decided it can no longer afford to leave the weapon of race-identitarian politics unused.

Enter Elon Musk.

Before dismissing the Tesla and SpaceX boss’s vision of open racial conflict outright, it is worth steel-manning it — internet parlance for presenting the strongest version of an argument before proceeding to contest it. Musk’s framing resonates because it speaks to genuine disorder that many associate with race. Crime has risen in some cities. Immigration has strained administrative capacity. Progressive elites have often appeared more interested in moral signalling than in competent governance. Many citizens reasonably feel that institutions no longer enforce rules impartially or tell the truth about trade-offs. Against such a backdrop, warnings about social fragmentation do not sound like hysteria. They sound like realism.

“Musk did not invent white identity politics. But he legitimises them.”

But realism requires discrimination and discernment. Musk’s diagnosis leaps from institutional failure to demographic destiny, from policy breakdown to fighting in the streets. That leap is not evidence-based; it is interpretive. And it is here that thoughtful analysis must reassert itself.

As I see it, the imagery Musk deploys draws on two sources: conspiratorial narratives about demographic “replacement”, and his own reading of civilisational failures in post-apartheid South Africa. In one widely circulated episode, Musk endorsed a post claiming that if white men were to become a demographic minority, they would face slaughter, and that only white solidarity could ensure survival. The meaning was unmistakable. This was not a critique of identity politics; it was a remarkably disquieting embrace of it.

Not long ago, open calls for white solidarity from a figure of Musk’s stature would have been politically radioactive. Today, they are met with a mix of alarm, rationalisation, and — in some quarters — approval. That shift itself is the real story. Musk did not invent white identity politics. But he legitimises them. His importance lies less in the sincerity of his beliefs than in his role as a permission-granting figure. When ideas migrate from fringe spaces into elite discourse, they change character. Errors that might remain contained at the margins become dangerous when voiced by powerful actors. Such is the case here.

Musk’s central error is conceptual. He is importing a post-colonial model of race politics into Western multicultural societies where it does not apply. Post-apartheid South Africa was not renegotiating the status of racial groups within a stable constitutional order; it was adjudicating the inheritance of the state itself. Questions of sovereignty, land ownership, elite replacement, and historical authority were all in play at once, in a context of racial domination and dispossession and a setting in which institutions were weak and legitimacy was racially compromised. Under those conditions, identity became destiny — because in the end, there was no other dimension along which to mediate political conflict.

Today’s pluralistic Western societies are not in that position. However bitter, their race-related conflicts take place within settled, universalist constitutional frameworks with entrenched property regimes and comparatively high-capacity institutions. Their arguments are about distribution, recognition, and status, not the wholesale transfer of political power. To read these conflicts as incipient post-colonial struggles is simply a grave category mistake.

What makes this mistake so consequential is that it is structurally enabled by a political culture already organised around identity. Once politics is understood — on Left and Right alike — as a contest among morally freighted groups, the temptation to treat race as a civilisational variable becomes overwhelming. In that context, Musk’s rhetoric is weirdly logical. It mirrors the structure of progressive racialism while reversing its moral valence. History still marks groups, in this view. Power still reproduces itself through institutions. Racially disparate outcomes still function as moral evidence. Only the identities of the winners and the losers, the offenders and the victims, have changed.

Whether Musk genuinely believes in white cultural superiority is beside the point. What matters is the effect on the discourse. Once race is treated as destiny, society reorganises itself accordingly. Institutions, insofar as they operate according to the disavowed pluralist precepts, fade into irrelevance. Demography becomes fate. Politics become a struggle for survival among groups. Race war seems to be imminent.

Institutional realism provides the best alternative to this logic. A serious response to rising crime asks whether policing, prosecution, and punishment are functioning coherently. A serious response to immigration asks whether borders are enforced, asylum systems administered, and newcomers integrated through work and civic obligation. A serious response to inequality asks how education, housing, and labor markets actually operate, rather than how they are symbolically narrated. These are institutional questions. They admit of failure, reform, and learning. They do not require racial metaphysics or “civilisation-or-barbarism” histrionics.

This is also, in part, a story about the evolution of the American Right. Identitarian, white racial paranoia on the Right has filled the vacuum created by an earlier ideological unraveling. After World War II, the so-called fusionism associated with William F. Buckley and his National Review magazine attempted to unite three distinct, occasionally contradictory strands of American conservatism into a single governing philosophy: economic libertarianism, a hawkish foreign-policy , and moral traditionalism. The viability of that alliance depended on general conditions of peace and prosperity in the United States, and a kind of gentleman’s agreement that adherents of each strand would mostly overlook their disputes with the others. They were stronger together than apart. And it helped that they were together in the trenches against a common foe: Soviet Communism and those who sought to expand its influence in the West.

“Identity politics offers a mirage of moral clarity without institutional analysis, and solidarity without responsibility.”

But then Communism collapsed; the shared enemy went away. The forever wars and financial crises of the millennium’s early decades broke the accord, with neoconservatism discredited abroad, libertarianism discredited at home, and religious traditionalists left to pursue their own ends. The rise of Trumpian populism marked the definitive end of the fusionist project. But Trump’s distaste for consistency created an ideological vacuum, and a need for a coherent program to organise the resentments he brought to the surface.

It would now appear that identity politics rushed in to occupy the space, because it is emotionally energising and cognitively cheap. It offers a mirage of moral clarity without institutional analysis, and solidarity without responsibility. Racial fatalism on the Right thus functions as a substitute for a serious account of institutional decay.

The deeper tragedy is not that identity politics has migrated from Left to Right, but that it has become the shared grammar of political conflict itself. We now argue loudly about which identities deserve protection or priority, but we no longer argue about whether identity is the proper battlefield. That tacit agreement is more troubling than any particular tweet. For once that terrain is fixed, escalation becomes inevitable.

Liberalism’s achievement was never the denial of any group’s level of historical suffering, but discipline in managing the present. It sought to thin out identity enough that a sense of shared citizenship could survive our grievances and differences. That achievement is fragile, and it is now under open assault — from a Left that moralises identity and a Right that weaponises it.

If the most influential figures in our public life continue to teach citizens to read pluralistic democracies through the lens of post-colonial struggle, the consequences will not be confined to rhetoric. Today’s permission structures become tomorrow’s political programs. Ideas that begin as tweets harden into expectations. Right-wing advocates of identity politics promise a restoration of order. What they will more likely produce is the acceleration of distrust and a descent into chaos.