Bob Weir’s death was surprising but not a shock. Grateful Dead fans have had plenty of practice saying fare thee well to other band members, most prominently Phil Lesh, Jerry Garcia, and Ron McKernan (aka Pigpen). Weir, who died Jan. 10 at 78, kept the Dead spirit alive after Garcia’s death in 1995 (just after turning 53), and with his passing the band’s music moves into a new realm. Never again will it be performed by the people who created it (holograms need not apply). A veil of sorts has fallen over the Skull and Roses.

On the bright side, Weir left behind vibrant memories that spanned and connected generations. He also dreamed big.

I saw my first Dead concert on September 11, 1973, at William & Mary Hall in Virginia. Those were the days. Ticket prices were $4, $5, and $6. A carload of us drove 120 or so miles to the show, where the band played through a prototype of its legendary “wall of sound” PA system, which rose majestically into a thick cloud of partially illegal smoke. The crowd responded like evangelicals beholding a retooled Rapture.

I was able to amble down to the elevated stage and parked directly below Weir. He was eight years older than me and could have passed for two years younger. Just as I arrived the band broke into an old cowboy song, Marty Robbins’s “El Paso,” spiced to perfection by Jerry Garcia’s joyful guitar. The effect was further enhanced by Weir’s dramatically widened eyes, which appeared to be no more than three micrograms short of flying from their sockets and landing in my shirt pocket.

Just after the announcement of Weir’s death, my oldest son and I listened to recordings of that Williamsburg show (it is the rare Grateful Dead performance that went unrecorded). The playing was superb, including on Weir’s “Weather Report Suite,” to my mind his most interesting piece of music. Also present at that show was Bruce Hornsby, a 19-year-old Williamsburg pianist who would later play around 100 shows with the band. For Hornsby the concert was transformative—”that was totally it for me,” he recalled in a 2023 podcast. “I love the music, and I love the attitude, the mindset, the aesthetic.” To top off the bliss, the band ended the show by announcing it would return the next night. Ticket price: $3.

I stopped seeing the Dead in the early ’80s—too much noodling can set aging heads to nodding—but my son (born in 1982) eventually caught the fever, which my wife and I considered a far better fate than being taken captive by Marilyn Manson. We scored tickets to a late June 1995 show at Robert F. Kennedy Stadium, where things got off to an electrifying start when a few fans were struck by lightning (they survived). While Bob Dylan played a solid opening set, the Dead seemed to have nine toes in the grave and a stiff wind at their back. Garcia died a few weeks later, on Aug. 9, reportedly with a smile on his face.

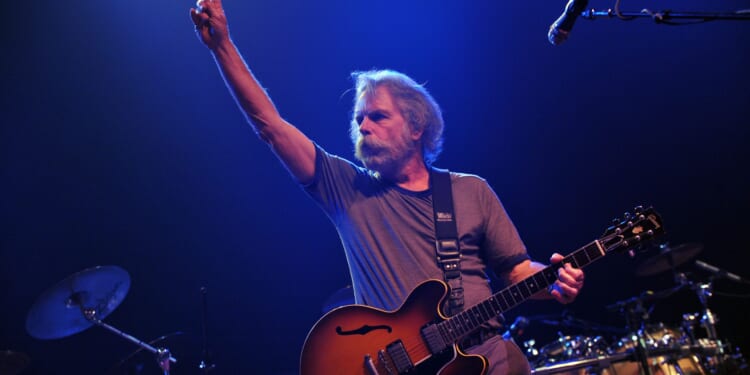

The ever-youthful Weir kept on truckin’. We caught him at Bill Clinton’s 1997 inauguration bash, where he and his band RatDog (joined by Rickie Lee Jones) warmed up a frigid Mall crowd with “Wang Dang Doodle” and other selections from the contemporary canon. We took in a few “Further” festivals featuring former Dead members, and my son ended our Weir-watch a decade ago with a Dead & Company concert at Shoreline Amphitheatre south of San Francisco. Weir had by then grown an impressive set of white whiskers (he said he reminded himself of a Civil War cavalry officer) and played, as my son put it, like a man looking back and reinterpreting his life’s work, not like an old rocker “trying to act like he was 25.”

Weir was a countercultural deity, but also a regular guy. Born a few years after World War II ended, at 16 he co-created the band he would stick with (in its various forms) until he was close to 80. A careerist, in his own way, he worked hard, made payroll for his crew, and raised a family. His fortunes also rose: Tickets to Dead & Company shows at Las Vegas Sphere went for $395 for mid-range seats; VIP packages, it’s reported, sometimes reached $3,000.

He was remembered at San Francisco’s recent “Homecoming” celebration as a lifelong Democrat who practiced tolerance toward the “Repubs”—a spirit currently in steep decline. He also dreamed that Grateful Dead music would be around in 300 years—a significant hope, though perhaps no more ambitious than the attempt by another ’60s-era band, the Fugs, to levitate the Pentagon during a 1967 antiwar march.

Those truly were the days. And to borrow an old Dead lyric—they most likely won’t be coming back. RIP.

Dave Shiflett posts his original music and writing at Daveshiflett.com.