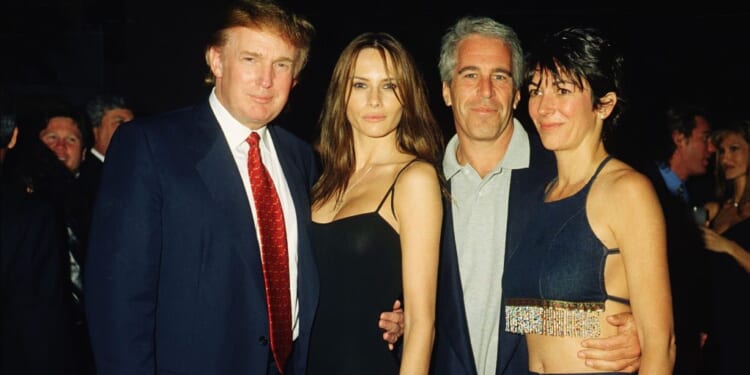

The latest tranche of material from the Epstein files has led to claims that resemble something out of the wildest espionage thriller: that the world’s most notorious sexual predator was also entangled in “sexpionage”. He would allegedly supply his rich and powerful guests with Russian women, many of whom could have been working for the Kremlin.

Journalists parsing the files have found thousands of references to Vladimir Putin and to Russia. There is still no proof that these files relate to a real espionage operation, in which victims were blackmailed after sordid encounters with Russian women. But connecting the dots leads to what sounds like an absurd conspiracy theory, where some of the world’s most powerful men, men with security teams and agencies meant to guard and protect them, were left exposed to an age-old, tried-and-tested Russian trick: the “honeytrap”.

The honeytrap is as straightforward as espionage manoeuvres come: the sexual seduction of a target is photographed or filmed then used for blackmail. In return for keeping the indiscretion secret, the blackmailer demands information or political favours. If the Epstein case was a honeytrap, who can know what Epstein, his guests, or his Russian contacts knew, agreed to, or wanted? But what is certain is that the scandal summons up the memory of honeytraps long past. It’s precisely because it sounds like pulp that the scandal now lands with such force in a political culture already primed to believe the worst about elite networks and hidden influence.

If the Epstein story has provoked hand-wringing and disbelief in the West, the reaction in Russia has been something closer to glee. On Russian Telegram channels, nationalists and Kremlin-supporting patriots are delighted. The dominant tone is a rolling mix of mockery and derision. But it’s also permeated with a sneering commentary on the West’s “perverse ecosystem” which permits such behaviour, combined with a knowing scorn for a tabloid culture that yearns for Russiagate tapes and kompromat porn. One widely shared post treats the entire affair as confirmation that Western elites are decadent, hypocritical, and permanently compromised. But it also says that claims about Russian involvement are false, cooked up by “British spies”. Indeed, another user dismisses the entire story as “the invention of deranged Brits”.

Alongside this ire runs something even less subtle: unalloyed delight at the West’s rich and powerful looking ridiculous. One popular channel revels in the image of Western financiers, politicians, and intellectuals undone not by some grand geopolitical strategy but by their own uncontrollable sexual appetites. Should they exist, these Russian women should not be ashamed of degrading themselves or being trafficked, say the Putin supporters. Instead they should be proud: they have fulfilled their patriotic duty by undermining the West.

In this framing, Epstein is not an aberration or a one-off monster, but merely the latest episode in a long and satisfying history of honeytrap stings on Westerners that reveal their sexual avarice. Proof, once again, that the West cannot be trusted to govern itself morally and that Russia is the world’s real bastion of “traditional values”. Sex trafficking, simply put, is less a tool for corrupting the West than for revealing its inherent corruption. Thus some Russians cheer the Epstein scandal as the latest example of their spy agency’s most beloved technique.

“Sex trafficking, simply put, is less a tool for corrupting the West than for revealing its inherent corruption.”

The history of Moscow’s honeytrap operations runs back to the early Cold War days. The KGB professionalised seduction with an almost bureaucratic seriousness. Female agents known as lastochki — “swallows” — were trained to target foreign diplomats, journalists, soldiers, and businessmen. There was remarkably little shame in the Russian secret services about using underhanded or dirty methods. Former KGB “swallows” later described their work as patriotic duty.

Honeytraps were a common feature of everyday espionage. Diplomats were told to assume that everybody they met was an agent and, accordingly, to behave with discretion. Bars and clubs, especially in the homosexual underground, were constantly monitored. Foreigners visiting Moscow were funnelled through official Intourist hotels staffed and monitored by NKVD and KGB personnel. Soviet women were deployed by the security services, sometimes to target a specific individual and sometimes to seduce any Westerner they could. Anyone, wherever they sat in the social or political hierarchy, could be targeted — after all, even low-level functionaries might still have some useful information. Rooms fitted with hidden cameras and microphones ensured that sexual encounters were recorded. The kompromat factory was a nationwide affair.

A compromised Westerner might never be contacted at all. Some ignored the KGB’s threats: the American columnist and CIA operative Joseph Alsop was compromised in a gay honeytrap in Moscow in 1957 but rejected the ensuing blackmail attempt. Counter-intelligence prevented other scandals getting out of hand: Sir Geoffrey Harrison, Britain’s ambassador to Moscow, was recalled after being confronted with compromising material in 1968. Others proved more pliable: Clayton Lonetree, a US Marine guard, was seduced in the Eighties by a woman posing as a translator and went on to pass sensitive information to Soviet handlers.

The honeytrap was so effective because it was a ruse that gathered intelligence which also produced explosive political material that could damage Western democracies. The classic British example is the case of John Vassall, a junior Admiralty clerk who was photographed in a homosexual encounter in Moscow in 1954 and for several years passed classified information to his handlers. When the case finally became public, the scandal caused huge embarrassment to then prime minister Harold Macmillan’s government by exposing failures of vetting, security, and judgement at the heart of the British state.

But the Russian state’s security organs don’t only use the honeytrap strategy on Westerners; they sometimes use it on their own citizens. It has been deployed against Putin’s challengers, such as the opposition leader Ilya Yashin who was subjected to a crude attempt to undermine his political credibility by letting him drown in a moral quagmire of his own making. In Russia, humiliating and denigrating an opponent is politics as normal; the same offensive tools used against Western targets are just as easily deployed against Russians by a Kremlin that’s terrified of both internal and external threats.

The honeypot approach is still used because it’s blunt but effective. It uses kompromat sometimes in exotic, outrageous forms, but just as often in banal, almost bureaucratic ways that resemble those of the Soviet era. One entirely ordinary Estonian soldier, for example, was seduced on a trip to visit family in Russia and subsequently convicted for espionage.

It would be a surprise if sexual blackmail is not being deployed against high-level Western businessmen, diplomats, and politicians today. Russia does not primarily seek to attack the West by surgically extracting targeted information, as traditional espionage would. Instead, it seeks to embarrass, humiliate, and degrade Western societies into destroying themselves by widening existing political fissures and disagreements and watching as a story-hungry media and viral social media storms do the hard work.

From Moscow’s perspective, it doesn’t matter so much whether the latest poisonous claims in the Epstein files are true. Even if the most sensational claims about who is (or who isn’t) a Russian agent collapse under scrutiny, the story itself will please Putin immensely. It will fuel suspicion that, regardless of their political orientation, the rich and powerful in the West can commit moral aberrations with impunity, and that institutions will shield them from consequence, instead of investigating them.

Backed by a group of supporters with no moral limits when it comes to undermining the West, the Kremlin will surely keep drudging up kompromat. But next time around, it may not need to wait for some hapless Westerner to fall into its trap. In the age of hacking and AI fakery, anybody, anywhere can be made the target of such blackmail. The future honeytrap does not need hotels and hidden cameras. It will be enough to make Western publics ask only whether something could have happened — and that, played out to the roaring crowd on social media, will achieve the Kremlin’s aims.