Ozzy was dead: to begin with. In Birmingham this December, we’re mourning not just the late great Brummie — but also the lost potential following the bankruptcy of the council and its abject failure of moral and social responsibility. Over £300 million in budget cuts have hit the poorest hardest, increasing inequality and leaving many Brummies to wonder why their leaders seem entirely without conscience.

Apt, then, that it’s also Birmingham which launched the most famous social conscience parable of all — Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol — as a performance piece. While Dickens lived a significant amount of his life in London, he chose the second city as the spiritual home for his 1843 Yuletide omen, which sees the moneylender, mortgagee and generally hated miser Ebenezer Scrooge experience an epiphany after visitations from a trio of ghosts.

This West Midlands focus makes sense. While Dickens uses London to symbolise the nation overall, Birmingham had long been the powerhouse of British industry — “the workshop of the world” — and the author had a lifelong relationship with the city. In The Pickwick Papers (1836), he describes Birmingham as being “thronged with working people. The hum of labour resounded from every house”; and “The din of hammers, the rushing of steam and the dead, heavy clanking of engines, was the harsh music which arose from every quarter.”

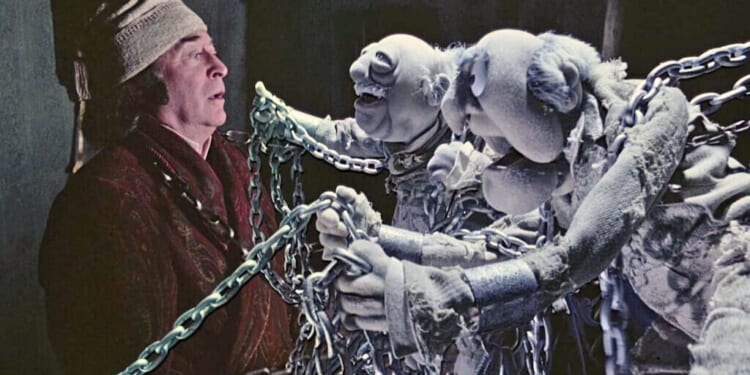

Despite the cartoons and fabulous Muppet adaptation, A Christmas Carol is not actually a cosy ghost story for children. Dickens was an ardent anti-poverty campaigner, and wrote the tale as a rallying cry across chattering cobbles for institutions and individuals to redeem themselves: by taking greater responsibility for the poor in their midst.

Today, of course, Birmingham is no longer the clangorous workshop of the nation. Its furnaces have cooled and the chimney smoke has been replaced with ELF Bar vapour. The city has seen a steep decline in production in the 20th and 21st centuries. In the Sixties, half of the city’s employment was in manufacturing; in Thatcher’s first term, one-in-four manufacturing jobs in the UK disappeared, with Birmingham and the North bearing the brunt of deliberate de-industrialisation. By 2006, Birmingham’s manufacturing jobs had declined by 80%.

But the city’s employment is still dominated by working-class roles — and salaries, with the median gross annual pay just £33,952 compared to the England average of £37,617. The majority of jobs are in social care, wholesale and retail trade, motor vehicle repair, and manufacturing. Overall, employment stands at just 66%, compared to the English average of 76%. And of the country’s eight largest cities, Birmingham has the highest percentage of households on Universal Credit.

There are grim parallels here with Victorian Britain. In 1839, there was a serious slump in international trade, which — alongside multiple crop failures — led to the “Hungry Forties”. Britain experienced an economic depression and a steep increase in unemployment, so people flocked to industrialised cities that were already bursting at the seams. In 1849, engineer and sanitarian Robert Rawlinson visited Birmingham and published a report: he found widespread problems with drainage, housing-quality, sewage and availability of fresh water. By 1852, Birmingham’s population was 250,000 strong, and many were suffering.

Dickens was invited to an event at the Society of Artists, where he recognised the potential of the city’s people. Talk turned to the founding of an organisation concerned with the promotion of education and learning in Birmingham, a town where only half of the children received education of any kind. He offered to do a series of talks the following Christmas to help fund it. He was true to his word, writing in a letter that he desired to read his 1843 bestseller A Christmas Carol to “the town folk either on one or two nights” to benefit the new institution, and that he wanted to have a “large number of working people in the audience” admitted for free. This would be the first time the now-iconic story had been performed in public by its author.

Adorning full evening dress, Dickens took to the stage of Birmingham Town Hall and performed the first ever public readings of A Christmas Carol on the 27, 28 and 30 December, 1853. It was a huge success. The performances not only raised the funds required to establish the new Birmingham and Midland Institute, but provided a lucrative second act to Dickens’ career — launching him as a touring performer of the novella. He would go on to do 127 such performances, which would ultimately become more profitable than his published works.

Over 10 years later, amid his deteriorating health, Dickens became president of the institute he had helped found. In a speech on 27 September 1869, just nine months before his death, he confessed to bearing “an old love towards Birmingham and Birmingham men”, before (thankfully) correcting himself, adding “and Birmingham women”. He brought attention to a ring gifted to him by Birmingham tradespeople over a decade earlier, and called it “an old Birmingham gift… if by rubbing it I can raise that spirit that was obedient to Aladdin’s ring, I heartily assure you that my first instruction to the genie on the spot should be to place himself at Birmingham’s disposal in the best of causes.”

A century and a half later, in December 2025, Birmingham-born actor Anton Lesser took to the very same Town Hall stage for a candlelight reading of A Christmas Carol, accompanied by an orchestra. The week before, Birmingham Symphony Hall screened A Muppet Christmas Carol, complete with an orchestra.

But the entertainment venues of Birmingham are now characters in a far less festive tale. Savage cuts to funding by the council have seen cultural sector investment slashed by 60% in 2024 — and 100% in 2025. As for the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Britain’s first publicly funded symphony orchestra, it is now left to find funding from the private sector, ending 105 years of council support. The Birmingham Royal Ballet and the IKON Gallery are also to lose council money entirely, alongside countless smaller venues and organisations.

Birmingham is, and always has been, a working-class city, but the council has seemingly forgotten this (or perhaps never knew it: one source told us that initially the council staff hired to liaise with community groups were not based in Birmingham and simply dialled in remotely for meetings about places they’d never visited). You sense a similar disdain for other bits of Birmingham heritage. After initially rejecting plans to demolish the building that currently houses Birmingham’s iconic Bullring market — in favour of either flats, student bedrooms, or a combination of the two — the council finally agreed to let the redevelopment go ahead. At a stroke, 900 years of trading history will be destroyed, a cultural disaster for a town built on commerce. ““Brummies feel very strongly that the markets are where people from all backgrounds come together,” says Professor Carl Chinn, a legendary local historian. “We’re losing who we are, our heart and soul. This is part of the ongoing gentrification of the city centre.”

“Birmingham is, and always has been, a working-class city, but the council has seemingly forgotten this.”

Birmingham’s centre is crucial to the wider area’s economy, accounting for at least a third of its economic output. In 2003, it was reinvented as a shopping destination, the centrepiece of which was the Selfridges building: either a monstrous carbuncle or iconic piece of skyline depending on your taste. According to the press release at the time, the building’s architecture was intended to be “soft lines of a body, rises from the ground and gently billows outwards before being drawn in at a kind of waistline…” In other words, it’s tits in a frock. But the sex appeal worked, and, combined with an ambitious 2011 investment plan by the then-Conservative-run council, Birmingham is now the most visited retail destination outside London.

New city-centre flats are likely to be snapped up by investors for the rental market. Certainly, the 40% of Birmingham’s population under 25 is unlikely to see much benefit, especially with a projected 19% rise in property prices. While there is an unprecedented demand by young graduates seeing Birmingham as an alternative to London, the housing problem is also driven by a major gap between demand and supply of social housing, growing families, and house prices disproportionate to income. All the while, 53% of local children live in the 10% most deprived areas of England, with 46% struggling in poverty.

These are not crises that will be solved by city-centre apartments or profiteering investors, and makes a mockery of Birmingham’s glossy marketing as a progressive and investable city: especially when private investment (and thereby profit) seemed to take priority over the basic welfare of Birmingham’s citizens. Labour took over running Birmingham in 2012, and everything got a lot worse. In 2023, the council issued a section 114 notice, effectively declaring bankruptcy. Birmingham is also the council with the biggest budget deficit in the UK, even as, according to data from Shelter, it has the highest spend on temporary accommodation outside of London.

In A Christmas Carol, before the clock strikes 12, the ghost of Christmas Present reveals two ragged and scowling urchins, Ignorance and Want, children representing problems that — if left unaddressed — will cause “doom” down the line. Dickens was aware, in other words, that the key to lifting children out of poverty is opportunity and education: which requires deep investment in education and resources. Unfortunately, this is yet another area in which Birmingham’s leaders are failing. In 2024, the council announced plans to entirely close or significantly reduce the opening hours of 25 of its 35 libraries. And this in a city of which Dickens once boasted: “I believe there are in Birmingham at this moment many working men infinitely better versed in Shakespeare and in Milton than the average of fine gentlemen in the days of bought-and-sold dedications and dear books.”

A final twist in the tale for Birmingham residents is that, alongside savage cuts to essential services and the selling off of assets to raise £750 million, council tax has risen by 7.5%. That is to say, the poorest and most vulnerable are bearing the cost of their politicians’ failings, the social fabric of the city made threadbare while landlords and investors count their profits. This Christmas, the ghosts of Ozzy Osbourne and Charles Dickens will be rattling their chains in the council offices, aghast at a city that has learnt nothing from historic warnings. Despite council leaders badly needing a festive moral epiphany, they seem determined to play Scrooge.