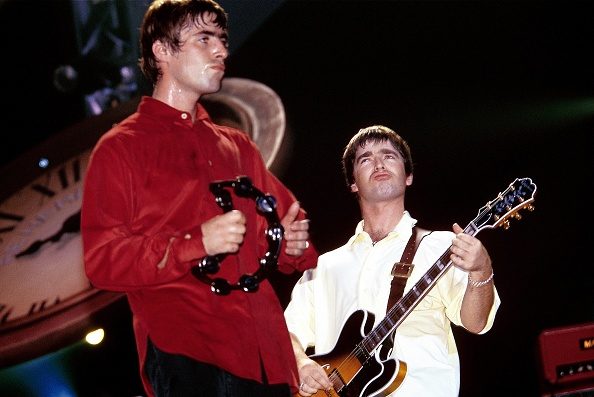

Thirty years ago, as Britain laboured under an unpopular government in terminal decline, and sweltered under the longest heatwave in many years, the August silly season was dominated by the press-confected battle between Oasis and Blur for the Number One single. The two bands were presented as rival national archetypes: the raw and cocky post-industrial North going head-to-head with the arch and arty representatives of the middle-class South for the nation’s affections.

Now that the era has passed into the kitsch bricolage of nostalgia, with Zoomers dressed like Kevin the Teenager flocking to see Oasis’ stadium tours alongside nebbish politicians in bucket hats declaring that they’re “mad for it”, it is hard to see the mid-Nineties as anything other than a golden age. Paunchy ageing dads — my own demographic, sad to say — fondly remember gelling down the fringes of their Caesar haircuts, donning their knock-off Ben Sherman shirts and drenching themselves in CK One before hitting the town with a tenner in their pocket. Yet it is a measure of Britain’s extended national decline that the mid-Nineties, today remembered as a halcyon era, was at the time experienced rather differently.

In a 1996 speech, the aspiring prime minister Tony Blair warned that “I see two futures open to this country. In one, Britain’s communities follow the process that has occurred in some places in the US, where the affluent have retreated into fortresses with private security guards, leaving the rest to live in ghettos of low opportunity, crime and insecurity. But the cycle of decay and economic underperformance continues. This is the Blade Runner scenario.” The other scenario, naturally, was for the country to vote New Labour into office. The influential 1997 Demos paper, “Britain™”, observed that abroad, “the general perception [is] that the UK, and London in particular, is not a safe place, with people living under the shadow of IRA bombs, homeless on the streets and racial tensions”, while “even the Union Jack has become an ambivalent symbol — at times a racist icon for skinheads and fascists”. Its solution, which we live with today, was to rebrand, and remould, Britain into a young and multicultural country, “the least pure of European countries, more mongrel and better prepared for a world that is continually generating new hybrid forms”.

Yet if the flags currently flying on lampposts across England, transforming suburban York and Birmingham into a simulacrum of the Lower Shankill, represent the reaction to this experiment, it is instructive to remember that the era, punctuated by racist murders and the rise of the BNP, witnessed its own contested politics of the flag, and conflicted attitudes to Britishness and Englishness. When, in 1992, the mournful Manchester-Irish troubadour Morrissey draped himself in the Union Jack, in front of a vast image of two skinheads, to perform “The National Front Disco” and caution his fictional “Bengali in Platforms” to “Shelve your Western plans/‘Cause life is hard enough when you belong here”, the response from the music press was not acclamatory. “Flying the flag or flirting with disaster?”, asked a rhetorical NME headline. Yet five years later, when the girl band bawd Geri Halliwell could strut on stage in a sequinned Union Jack minidress, the national flag was not only not controversial, it had become ubiquitous in popular culture. What had happened in between was, simply, Britpop.

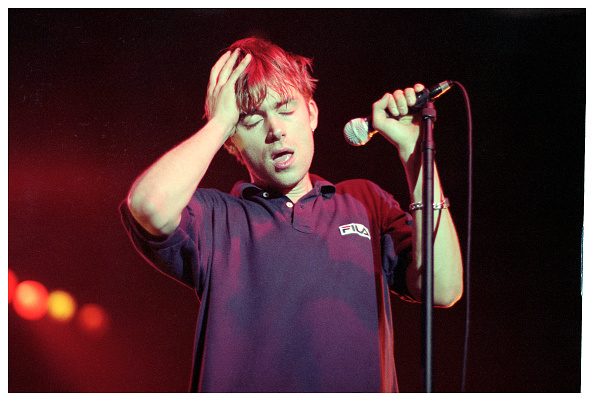

Was Britpop’s cultural nationalism ironic or sincere? As the brains behind Vanity Fair’s famous “Cool Britannia” cover, Toby Young — now firmly ensconced within the British Right — observed, a new generation had emerged that “had grown up loathing and despising American mass culture” and “felt a kind of nationalistic resentment”. Blur returned from a dismal 1992 tour of small-town America filled with loathing for the imperial hegemon and a conflicted love for England and home. “What is it about home we’re missing?” the group’s drummer Dave Rowntree pondered, “What is it we like and that we don’t like?” They set about working on their second album, Modern Life is Rubbish — its working title was Britain Versus America — which, with its inward-looking cultural references, both mocked and celebrated small-town English life, and defined the Britpop aesthetic. Choosing, as Blur’s guitarist Graham Coxon notes, “a Ladybird Books-style painting of the classic Mallard locomotive” for its cover because “nothing could be further from what most people expected of an alternative rock LP”, the album had strangely conservative vibes which belied the group’s profession of Left-wing values. Drawn from the provincial lower-middle-class of Southeast England, the children of teachers, Army bandsmen and a South Coast BnB-owner-turned-rubbish-compactor, the group was shaped by the values of their upbringing. “My family, like most army families, was pretty conservative and patriotic,” Coxon remembers. “It was generally assumed that you supported England in everything it did.” Coxon’s autobiography is infused with the memories of a postwar English childhood, of grubbing for “smutty magazines” inside abandoned pillboxes at a time when “‘Tommies versus Jerries’ were popular pastimes in the school playground”.

Like his cultural distaste for America, Blur’s singer Damon Albarn’s self-professed political radicalism is likewise shot through with a very English conservatism, condemning his Essex peers for their crass Thatcherite materialism and lamenting that “The colour and vibrancy of the countryside was destroyed… literally fields I was playing in one year were housing estates the next”. As John Harris observes in his excellent book on the Britpop era, Albarn’s Essex childhood home was in a rural hamlet where “the local accent has an archetypally East Anglian burr; when Albarn enrolled at the local comprehensive school, he rubbed shoulders with the children of agricultural workers”. Coxon remarks of the “Grantchester Meadows” quality of their childhood, “hanging out by the river at the back of [Albarn’s] house in the wilds of Essex”, that “our outlook was a little more bucolic and melancholic… A lot of that English local colour flavoured the music, right from the start.”

“Blur’s singer Damon Albarn’s self-professed political radicalism is likewise shot through with a very English conservatism.”

Oasis grew up in quite another England, if the Manchester-Irish milieu can be termed England at all: far from lazy summer afternoons, the group’s first incarnation was simply called “The Rain”. There is a particular recurring strand of Irish literature that focuses on unhappy households, dominated by a superficially charming but overbearing father, in which the devoted mother bears her lot unhappily and the sons plot their escape as revenge. The semi-official biography of Oasis by Paolo Hewitt slots right into the genre. The drunk, abusive Tommy Gallagher, from rural Meath, ruled his Manchester household through fear: divorcing him, against the priest’s advice, the family moved to a council house in suburban Burnage, “where each house has a garden”, and which “lies within walking distance of two golf courses”, as Harris notes with a Daily Mail-style eye for class minutiae wasted on The Guardian.

The Gallagher brothers were raised in the Irish diaspora milieu of Gaelic football, church social clubs and Irish dancing — and long summer holidays at their mother Peggy Sweeney’s family farm in rural Mayo where Noel Gallagher reminisces about picking blackberries, bringing in the cows for milking and drawing water from the well. Appearing on Gay Byrne’s Late, Late Show — then a staple of both home and diaspora Irish life — the young Noel Gallagher presented himself as a good sensible boy to the avuncular presenter (not least in the knowledge that his mother would be watching) claiming sentimentally that tears would well in his eyes at the scent of burning turf. “If you look at Gaelic bands,” Noel would tell Hewitt, “they always had these rousing, fist-in-the-air choruses. And I suppose it’s also because we have this rootsy, folk feel on some of the other songs which you get subconsciously from your childhood.” Or as Gallagher would correct a reporter at the height of 1995’s Battle of Britpop, “We’re not Britpop, because we’re Irish, for a start.”

Yet when the founder of Creation Records, Alan McGee, first met the group in Manchester, it was with the Union Jack behind them, which the band had painted on the wall of their rehearsal room. “Noel had even written a song called ‘The Red, White and Blue’,” notes Hewitt. “Their fascination with the British flag caused a little consternation among some onlookers… and there were various mutterings about the band’s politics.” The Union Jack, in distorted form, soon made it onto the band’s demo cassette. As Harris notes, “when a passing Creation staff member enquired about the design on the cover of the Oasis demo — the colours of the Union Jack arranged in a vortex, as if being sucked down the plughole — Liam dispensed a snarling reply… ‘It’s the greatest flag in the world and it’s going down the shitter,’ he said. ‘We’re here to do something about it’.” And so they did: like the RAF roundel, the Union Flag, whether on Noel’s guitar or the PR ephemera of the era, would become ubiquitous, just as the laddish fusion of football culture and Sixties revivalist pop would revive the St George’s Cross in common usage for Euro ‘96. “17 years of hurt never stopped us dreaming,” Blair would declare, “Labour’s coming home.” The world of the Blairite “Britpopper” had been born. It is one which Fabian thinktankers have never left.

For all its Blairite connotations, the first recorded use of “Cool Britannia” in British Politics was, improbably, by Virginia Bottomley’s Department of Media and Culture. But if the fragile mood of optimism inspired by a buoyant economy, recovering from the recession of the early Nineties, was the product of the Major government, the Conservative Party was in no position to capitalise on it. The attempted Rightward shift of Britain’s political culture, encapsulated in Major’s lyrical evocation of old maids cycling to church through the mist, had been wrecked, in a now familiar pattern, by the corruption, incompetence and sexual deviance of the party’s MPs: rather than being too conservative for the country’s voters, as contemporary accounts assume, the Tories were too libertine. In their wake would come Blair’s revolution, which co-opted Britpop, to gain a sheen of youthful credibility and optimism, with the eager collaboration of the music industry, in which, as Sleeper’s Louise Weber noted, “you could not criticise New Labour, you could not criticise Blair, it was verboten, not allowed”.

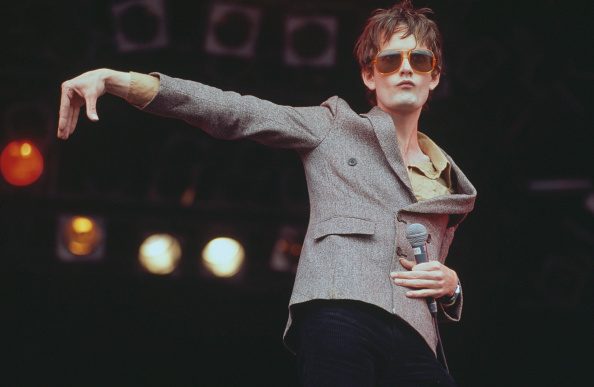

The many subsequent hagiographies of Britpop place great emphasis on the Sussex band Suede as the forerunners of the movement, also wrapped in the flag, against their will, by the music industry. It accompanied them on the 1993 Select magazine cover featuring Suede’s singer, Brett Anderson, beneath the title “Yanks Go Home”. Yet even Suede’s then-risqué androgyny and odes to amyl nitrate now seem curiously innocent, more Charles Hawtrey than Rimbaud. Indeed, all the frantic cosmopolitanism of the Nineties today seems quaintly parochial: Albarn’s increasingly cruel “social satires” of the small-town middle classes exude the status anxieties of the provincial FBPE activist, his various accents, careening all over the English class system, a Harry Enfield performance. Blur’s 1993 mockney stomper “Sunday, Sunday” plays with imagery of provincial ennui, Sunday roasts and war veterans, that while mocking, now reads almost as nostalgia for a world that then still existed. Even the Select piece that launched the movement, with its Dad’s Army graphics and declaration of a “Battle of Britain”, are products of that same insular postwar world, in which Noel Gallagher could reminisce about making Airfix models of Hurricanes and Lancasters, and the ageing Graham Coxon spends his free time at Tunbridge Wells’ War and Peace Show re-enactments, buying military surplus. The Britpop movement, ultimately, drew from the same cultural wellsprings Reform does today: from Blur’s PR jaunts to what is now Farage’s Clacton seat, to Oasis’s suburban childhood, flanked by golf clubs on the edges of Stockport, the provincial England then invoked half-ironically has now swung sharply to the Right.

For whatever else Britpop was, it was a celebration, if a patronising one, of England’s white working class, which would be far beyond the cultural pale today. As Pulp’s Jarvis Cocker would later note, “working-class culture was often sneered at as being crude and stuff like that but then people maybe cottoned on to the fact that it was a bit more alive than the supposedly highbrow culture”. Adopting an increasingly parodic cockney accent, in his war against the lower-middle classes that birthed him, Damon Albarn assumed that if there was hope, it lay with the proles. His then-girlfriend, the privately educated Justine Frischmann, likewise mars Elastica’s otherwise standout track Waking Up with the mockney suggestion to “make a cup of tea”, delivered in the tones of someone nervously appeasing a builder. Yet it was only under the Blairite consensus Britpop helped usher in that this very same culture became demonised: the cockney double-glazing salesman persona Albarn assumes in the Parklife video would very soon become Emily Thornberry’s St George’s Cross-hanging, white-van-driving nemesis.

“For whatever else Britpop was, it was a celebration, if a patronising one, of England’s white working class.”

Indeed, for all that nostalgic hagiographers of the era like Jon Savage can claim, ludicrously, that Oasis’s Some Might Say “captures the mood of the moment” of the Conservative defeat in England’s 1995 local elections, the band themselves were always ultimately an expression of Thatcherite social mobility, of conspicuous consumption and the polished Rolls-Royce in the driveway. The very cover of Oasis’s Definitely Maybe, with its stripped floorboards, glass of red wine and paper lampshades, expresses a working-class aspiration towards middle-class aesthetics — the renovated Victorian townhouses of BBC’s This Life — that the band would soon swiftly transcend. Where Blur, 30 years ago, mocked the urge of the newly wealthy to move to “a very big house in the country”, Noel Gallagher rapidly transitioned from playing at a Home Counties country house to buying one, from where he now delivers his recollections of the era on a throne-like wing chair. Blur’s Graham Coxon has retreated to true-blue rural Kent to explore “English indigenous folk traditions” from a barn conversion; Alex James to life as a country landowner and cheesemaker: the lures of Deep England, and of romantic conservatism, always win in the end.

What was Britpop then? Perhaps, in the end, just a confection of the spin doctor era. Like New Labour’s political mood music, it was always empty at its heart: Blur’s lyrics were always less clever than claimed, and Oasis’ less profound. Britpop died in 1997, shortly after Blair came to power: it was as if the movement had outlived its purpose. And just as the original bands of the era brought about a flurry of uninspired imitations, it has been our fate since then to be ruled by a dismal succession of Blair tribute acts.

Blair’s social revolution, his New Britain, buried the cosy postwar England that had birthed the movement, and gave Britain a new aristocracy of judges and NGO activists yet to be dethroned. In reward for its services, the new Blairite order installed a new cultural establishment, the commentators from the Britpop-era music industry who write Guardian thinkpieces, judge books and arts prizes, present BBC radio shows, and feed the stultifying incuriosity of the Radio 6 dad. Instead of evading his threatened Blade Runner future, Blair accelerated it: Oasis’s Don’t Look Back In Anger would soon become the anthem of the British state’s “organised spontaneity” to dissuade Manchester’s white working class from reacting to jihadist mass murder with anything other than the empty, swaying sentimentality of a stadium sing-along. Yet as Noel Gallagher himself observed, “These people have the right to be radicalised. They have rights… That guy who set that bomb off sees the streets of Britain as a battlefield — our leaders don’t see it as a battlefield.”

The insular, homely English culture Britpop both mocked and celebrated was ravaged by the political order it soundtracked. Only in retrospect does John Major’s Britain, then imbued with themes of decline, seem like a vanished golden age, the political horizon, before it all went wrong, of the radicalised Right-wing Zoomer. The era’s nostalgia for the Sixties has been replaced by today’s nostalgia for the country the Boomers destroyed. Once again, the nation is asking “What is it about home we’re missing? What is it we like and that we don’t like?” The Union Flag is omnipresent in England once again, for quite different reasons: the white working class Britpop championed, like the provincial lower-middle class it mocked, is in open revolt against the political and cultural establishment it helped enthrone, and it is the bourgeois Right-wing dancing to their raucous tune.