How well do the amendments to the US Constitution reflect the Founding Fathers’ original vision for America? First, the Framers intended the foundational document for the fledgling nation be a flexible framework.

Virginia’s delegate to the Constitutional Convention, Edmund Randolph, wrote on July 26, 1787:

“In the draught (draft) of a fundamental constitution, two things deserve attention: 1. To insert essential principles only; lest the operations of government should be clogged by rendering those provisions permanent and unalterable, which ought to be accommodated to times and events: and 2. To use simple and precise language, and general propositions, according to the example of the (several) constitutions of the several states. (For the construction of a constitution necessarily differs from that of law).”

The First Ten Amendments

The first ten amendments to the Constitution, ratified on Dec. 15, 1791, formed what is known as the Bill of Rights to protect individual liberties. The right to exercise religion; freedom of speech, of the press; the right to peaceably assemble and to petition the government for a redress of grievances. The right to keep and bear arms, to be free of unlawful search and seizure, and due process were enumerated first before the amendments that followed.

Laws of Nature and the Rights of Man

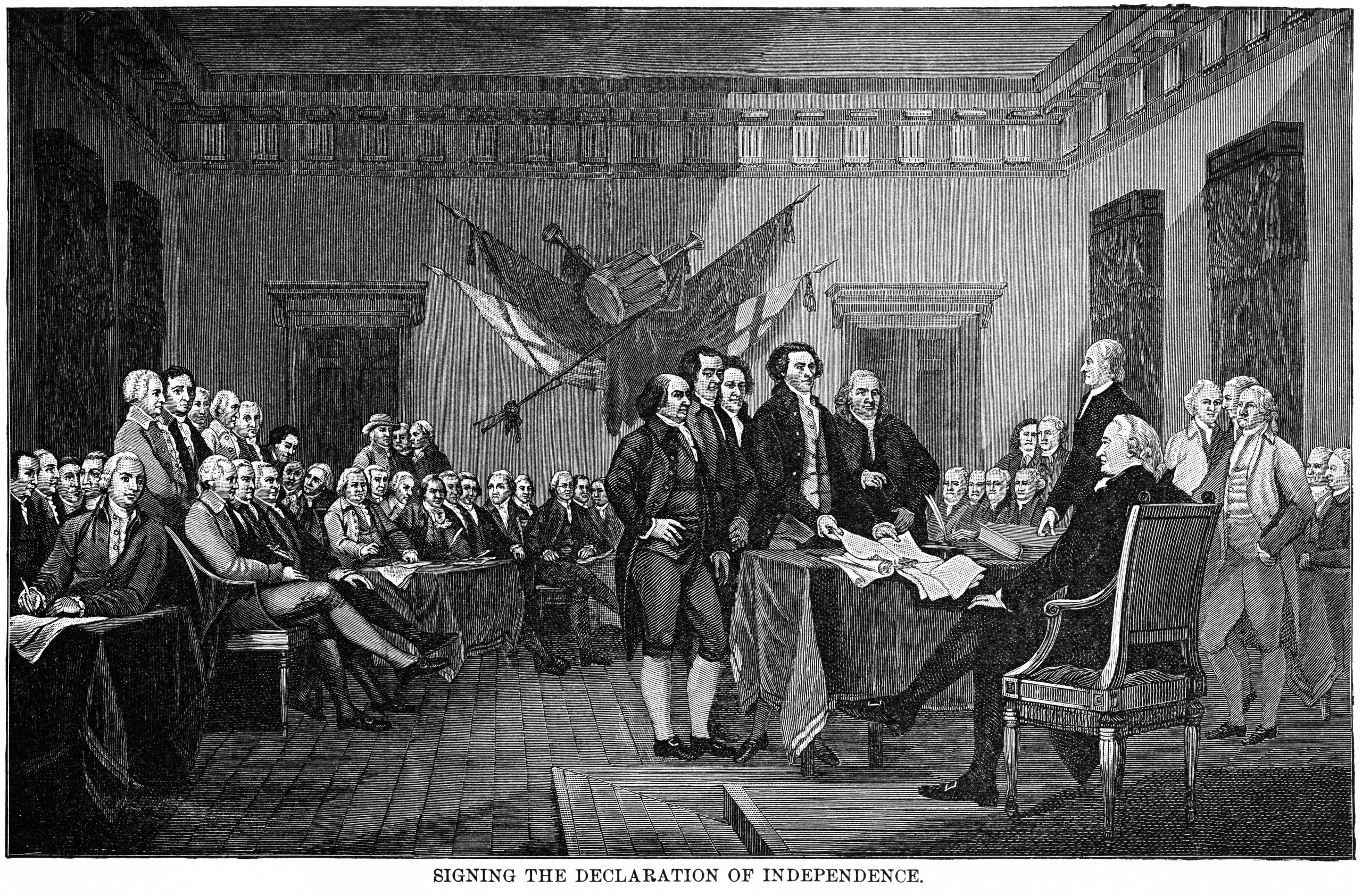

The Continental Congress formally declared the independence of the 13 colonies from the British Crown and approved the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, which says in part: “to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.” The Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God were the moral compass found in the Bible but accepted by even non-believers among the Founders.

Thomas West is a professor of politics at Hillsdale College and the author of the book The Political Theory of the American Founding. In Hillsdale’s online course, The Real American Founding: A Conversation, West gave an example of the Laws of Nature and Nature’s God:

“The idea that one should not harm another person’s life, liberty or property, or take away their right to pursue happiness. The Natural law is the foundation, as they understood it, of the rights of the individual. And so all those human rights mentioned in the second paragraph to the Declaration are comprised under, or derived from, the laws of Nature mentioned in the first … A duty not to enslave; there’s a right to liberty.”

West said the Founders had consensus about America declaring independence, but there was conflict on natural rights. Slavery bore witness to that. The majority of our Founders, even if they were slave owners, believed all men were created equal, West said. In 1776, every American colony had slavery. West said Thomas Jefferson would leave that up to future generations to figure out. And they did.

Accommodated to Times and Events

As the Founders designed, the Constitution was accommodated to times and events with several amendments that expanded individual rights.

The Founding era from 1791 to 1804 brought the first 12 amendments, including the Bill of Rights. Scholars often refer to the Reconstruction era, between 1865 and 1870, as America’s “Second Founding,” which brought three transformative amendments. Slavery was abolished with the 13th Amendment, American citizenship was granted to slaves under the 14th Amendment, and voter discrimination based on race was prohibited with the 15th Amendment. These all align with the Founders’ political theory of the Natural Laws and the Rights of Man.

The 16th through 19th amendments were added to the Constitution during what is known as the Progressive era, between 1913 and 1920. The 16th Amendment gave the federal government the power to impose the income tax, reversing a prohibition in Article 1 against a “direct tax.” The 17th Amendment gave the American people the right to elect senators. Women were granted the right to vote in the 19th Amendment, and the 26th Amendment lowered the voting age to 18 years old.

The final eight amendments were gradually added during the modern era, over the span of 60 years between 1933 and 1992. The 20th Amendment established the presidential term and succession and how Congress would assemble, and the 22nd Amendment set the two-term presidential limit. The latter was a check and balance on the power of the Executive Branch that had grown. The 23rd Amendment granted residents of the District of Columbia the right to vote in presidential elections.

As a whole, have the constitutional amendments strayed from the Founders’ vision for America? The vast majority did not. The final one, ratified in 1992, was first proposed by James Madison in 1789. Madison himself oversaw the formation of a list of 12 potential amendments, including this one. Meant to be added to Article I, Section 6 of the Constitution to prevent corruption in the legislative branch, the 27th Amendment is an interesting bookend to the flexible framework of the founding document: “No law, varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives, shall take effect, until an election of Representatives shall have intervened.”