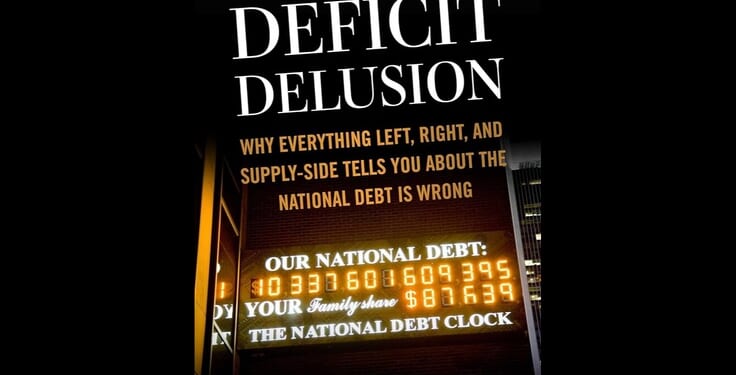

John Tamny, the free-market economics commentator who edits RealClearMarkets, comes out swinging in The Deficit Delusion: Why Everything Left, Right, and Supply-Side Tells You About the National Debt Is Wrong. Perhaps this isn’t surprising, given the book’s title. It can feel like Tamny is a kid walking through the elementary-school playground, randomly shoving other kids—some of whom are bigger than he—as he attacks one op-ed writer after another for, allegedly, misunderstanding the national debt.

In his view, it’s a bunch of panic over basically nothing. The reason the United States has so much debt is simply that we have a good economy and a lot of tax revenue, which makes investors trust they’ll be paid back and thus willing to lend at low interest rates. If we couldn’t handle the debt, they wouldn’t lend to us. To the extent there’s a real problem, in Tamny’s view, it’s that we’re spending too much—with government spending being a problem not for its effect on the debt, but because it’s a “horrid freedom- and economy-sapping tax.”

Nonetheless, in a fun twist, Tamny argues against reforming our entitlement programs, too. It’s a fool’s errand, because politicians will probably find something even worse to do with the money!

The Deficit Delusion is a delightfully combative and consistently surprising read, but it’s unlikely to change minds. Unfortunately, this deficit hawk came away still thinking we should get the debt under control and fix the entitlement system.

Tamny begins the book by explaining some basics about debt. It can be a sign of safety and trust.

Start-up companies, for example, are extremely likely to fail, and thus they have a lot of trouble borrowing money—there isn’t an interest rate high enough to cover the immense risk. Instead, they have to sell equity, or pieces of themselves, to raise cash, which makes their investors very, very rich in the event the company succeeds.

In 2011, venture capitalists bought 20 percent of Uber for $12 million. Today, 20 percent of the company is worth around $40 billion. Note that one of those starts with an “m” and the other with a “b.” Nowadays, by contrast, Uber has no problem issuing debt, and indeed has taken on around $10 billion worth of it. Its debt is a sign of its success. People are confident Uber will be around to pay them back.

By the same token, surely it says something good about the U.S. government that it even has the option of being tens of trillions of dollars in debt while continuing to borrow at low interest rates. It means that a lot of people trust the government to pay them back, either through future tax revenue or by “rolling over” the loans to a new set of trusting borrowers.

That’s a perfectly fair point. But Tamny takes it too far, rejecting even “the popular notion that the deficits and debt are a consequence of too little government revenue, too much government spending, or both.”

Isn’t debt, quite straightforwardly, the accumulated difference between our spending and our tax receipts, plus interest over time? Doesn’t it have to result from spending in excess of taxes?

This might be mathematically true, but Tamny sees a deeper reality. “[T]he deficits and debt are plainly a consequence of the U.S. Treasury collecting way too much in taxes now, and much worse, the expectation that Treasury will collect quite a bit more in tax revenues in the future,” he writes. “We have $36 trillion in debt (and counting) because Americans are prodigious creators of wealth that Treasury owns a piece of.”

This line isn’t the only time he presents the situation as straightforward cause and effect: We have a good economy and the government taxes it, which assures investors they’ll be paid back; therefore, as surely as night follows day, we have tons of debt.

It’s true that a big economy and strong tax revenue make the government able to borrow this much, and that politicians anywhere would find this tempting. But policymakers still had to choose to borrow rather than bring spending and revenue into closer alignment. Debt critics don’t wish the United States were too poor to borrow or lacked the infrastructure to collect taxes; they wish its leaders had chosen different spending and tax levels.

Meanwhile, though Tamny may not think the debt is a problem in itself, he does hate government spending. This, one might think, should give him common cause with at least some debt skeptics. But fascinatingly, the final chapter (before the conclusion) is called “Whatever You Do, Don’t Let the Deficit ‘Hawks’ Reform Social Security and Medicare!”

Unlike most Americans, Tamny isn’t a fan of these programs. They’re government spending, after all, interfering with the magic of the private sector. Yet he isn’t troubled by their effect on the debt, he knows they’re too popular to get rid of, and he actually thinks it’s a good thing that they’re soaking up government spending that might be directed elsewhere—perhaps to new programs that might one day grow just as quickly as the entitlements have. “[T]hink of how many aspects of American life will not be touched by the enervating hand of government,” he writes. “Let the ‘crowding out’ begin.”

Even if the savings from entitlement reform are used to pay off the debt, Tamny doesn’t see things ending well: “Paying off the debt doesn’t alter the cause of all debt, which is too much tax revenue now and way too much in the future, which means paying off the debt is like paying off the credit card of a profligate borrower: it will just enable even more borrowing.” Better to keep shoveling money at retirees than to spend it elsewhere or to pay back our debts.

It’s a spirited and counterintuitive take on an old issue, but it’s also a striking concession of one of the main points made by entitlement-reform advocates—namely, that high levels of spending on the elderly are indeed crowding out other priorities, including spending on children. And the idea that shifting spending to other priorities would be worse for the country, and perhaps even the higher-spending option in the end, feels thinly argued.

Americans should be grateful they live in a country that can take on loads of debt when it really needs to. It helped us weather the pandemic, for instance. But the case against our fiscal status quo—running ever-rising deficits as a matter of habit as our debt grows bigger than our annual GDP—has always been pretty straightforward.

When we put our spending on the national credit card instead of paying for it ourselves, we force future generations either to pay it back or to keep paying interest on it in perpetuity. High debt can also crowd out private investment (because the folks lending the government money could otherwise invest it in the private sector) and could lead to a painful reckoning years down the road if interest rates rise, though it’s impossible to predict exactly what this might look like or when it might happen. And when we let entitlement programs for the elderly spin out of control, we worsen these problems and, yes, make other priorities harder to fund.

Nothing in The Deficit Delusion convinced me otherwise. But it’s still a fun read, challenging debt-conscious readers’ preconceptions and encouraging us to take a deep breath before we go on panicking.

The Deficit Delusion: Why Everything Left, Right, and Supply-Side Tells You About the National Debt Is Wrong

by John Tamny

Regnery, 159 pp., $32.99

Robert VerBruggen is a fellow at the Manhattan Institute.