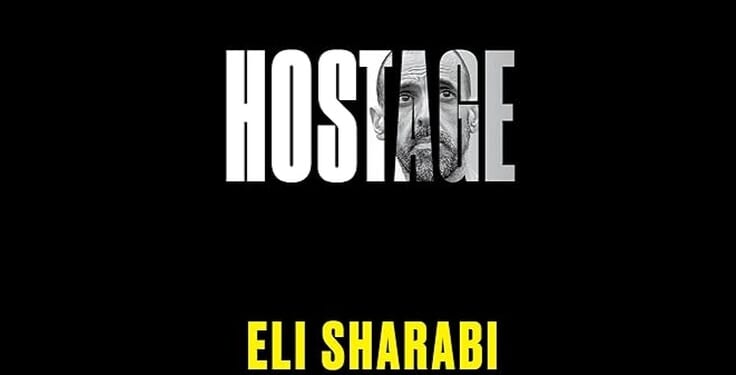

The first memoir by an Israeli hostage dragged into Gaza by Hamas on Oct. 7, 2023, is Eli Sharabi’s book Hostage. It was the fastest-selling book in Israeli history when it was published in Hebrew, and is now available in an English translation.

Hostage is a classic work about captivity—joining Natan Sharansky’s Fear No Evil about his years in the Gulag, and Viktor Frankl’s account in Man’s Search for Meaning of his years in Nazi concentration camps—examining the human spirit under the worst possible circumstances. It begins on the morning of Oct. 7 and ends with his release from Gaza after 491 days in captivity—and his visit to the graves of his wife Lianne and his daughters.

Sharabi’s account is short, under 200 pages, which makes it a work to be read at one sitting. In it we see him experience all the best and worst human traits: love, hatred, self-sacrifice, brutality and violence, terror, deliberate starvation, and determination to live. We know the outcome: He will live, and be freed, and will find that on the very first day his family was murdered. But he did not know that, and living for them was a key part of his own survival.

Sharabi was a resident of Kibbutz Be’eri on the Gaza border, like the other kibbutzim an almost ideal community turned in a few hours into places of slaughter, rape, kidnapping, and unspeakable cruelty. He explains his slow realization that morning of Oct. 7 that this was different: not another barrage of rockets from Gaza but an actual invasion—and the IDF was nowhere to be found to fight off the invaders. He was grabbed from the “safe room” in his home and understood what was happening: He was “totally aware that I am being abducted into Gaza, but knowing at least that Lianne and the girls were left behind, I focus and concentrate on one mission: surviving to return home. There is no more regular Eli. From now on, I am Eli the survivor.”

It is this mindset that saves Sharabi. He thinks of his family but says, “I refuse to let myself sink into longing. I refuse to let myself drown in pain. I am surviving. I am a hostage. In the heart of Gaza. A stranger in a strange land. In the home of a Hamas-supporting family. And I’m getting out of here. I have to. I’m getting out of here. I’m coming home.”

He quotes a young hostage who was, for a while, kept with him, Hersh Goldberg-Polin, who was later murdered by Hamas. Goldberg-Polin told him of the words he attributes to Frankl: “He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how.” Hearing those words from Goldberg-Polin, Sharabi thinks “the saying feels like a gift. It matches the spirit I am already in. Even before hearing the words, I’m already living them. I have a why. Many whys. And I’m focused on surviving, on living, on being. On returning, alive and well, to my family and my life. I have a why. … I can do this. I can survive anything.”

Frankl himself attributed those words to Nietzsche, and in Man’s Search for Meaning wrote this: “There is also purpose in that life which is almost barren of both creation and enjoyment, and which admits of but one possibility of high moral behavior: namely, in man’s attitude to his existence, an existence restricted by external forces.”

Sharabi had never read or heard of Frankl, though by now he has probably read the book. Sharabi’s own life in captivity is an almost perfect proof of Frankl’s understanding: Even in the worst of circumstances, a man can make choices about his life and how he sees his own existence. Sharabi repeatedly says to himself that he and the other captives are on a mission: “We’re on a mission to survive.”

Frankl wrote that:

The experiences of camp life show that man does have a choice of action. … Man can preserve a vestige of spiritual freedom, of independence of mind, even in such terrible conditions of psychic and physical stress. … Everything can be taken from a man, but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

For Sharabi, it is primarily returning to his wife and children that gives him purpose. He understands that women and children were also taken hostage, but says:

I’ve also got to believe that Lianne and my girls are alive. I’ve got to believe that Yossi, my brother, who also lives near me in Be’eri with his family, is alive. That he, his wife, and their children also survived the massacre and are waiting for me. I’ve just got to. Among all the possibilities constantly racing through my mind, I keep the worst possibility of all somewhere at the back, but I refuse to give it much space. I’m not going to dwell there. I’ve got to believe they’re all right so I can hold on for them, so I can survive for them. The belief that they were alive, my concern for them, gives me strength. They are my mission.

Yet it isn’t only for his wife and children that Sharabi fights; it is for himself as well.

I don’t want to survive just for them. I don’t want to live just for them. I want to live for myself too. For me, Eli Sharabi. I want to live. I love life. I crave it. … I use the cold, hard logic I’ve developed over the years. I tell myself: Eli, focus. It is what it is. This is the situation. You have no idea what’s happened to your family. You have no way of knowing their fate. You have no control over how much food you were given, no control over how clean your environment is, no control over your freedom. So focus on what you can control. Channel your strength towards the things you can manage—and stay yourself.

This is how Sharabi stays alive and sane through months of near starvation, cruelty from guards, psychological torture, beatings, and month after month in dank, airless tunnels deep under the earth.

The end of the story is tragic, because when he is released Sharabi is met by his mother and his sister—and immediately realizes what this means: that his wife and daughters cannot greet him because they are gone. They have been murdered. Sharabi demands to visit their graves, and breaks down and sobs there for 40 minutes. And then he tells his sister “let’s go.” It is, he writes, “a signal to everyone: it’s over, finis. I pick myself up and start walking slowly toward the exit of the cemetery. This here is rock bottom. I’ve seen it. I’ve touched it. Now, life.”

It’s impossible to read Hostage without asking how we would have dealt with these conditions: Would we have fought on and lived? How many of us could have managed one day or 10 with the commitment, courage, and sanity Sharabi maintained for 491 days, holding fast to his “mission” to survive? The story of this very extraordinary ordinary Israeli kibbutznik, this very typical husband and father and son, is a bracing memoir of how men can find the strength within themselves to resist evil and decide to survive. “Therefore choose life,” God commanded in Deuteronomy 30:19. That is what Sharabi did, and his story is captivating and inspiring.

Hostage

by Eli Sharabi

Harper Influence, 208 pp., $30

Elliott Abrams is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.