The moral task of American statecraft in our time.

“I, Wisdom, dwell with prudence (phronēsis), and I find knowledge and discretion. By me kings reign, and rulers decree what is just.” – Proverbs 8:12–14 (LXX)

“Practical wisdom (phronēsis) is a true and reasoned state of capacity to act with regard to the things that are good or bad for man.” – Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics VI.5–13

As Thucydides observed, the causes that drive nations to war—fear, honor, and interest—remain constant. A prudent foreign policy recognizes the powerful pull of these passions without surrendering to them.

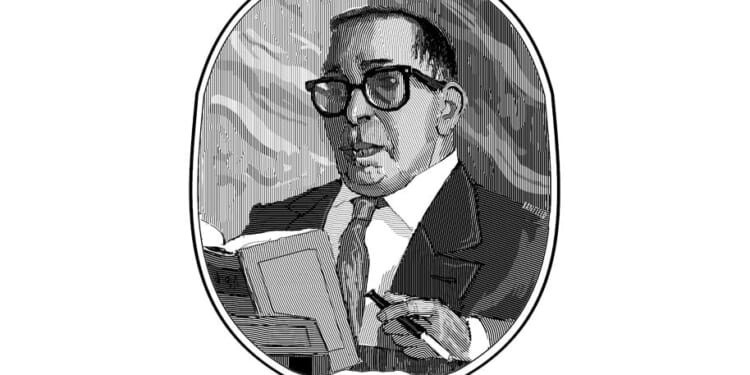

Leo Strauss is often accused of inspiring not only neoconservatism, a movement bereft of such wisdom, but specifically the vigorous interventionism championed by the most vociferous voices within its ranks. On the surface, the Platonic rationalism that searches for the discoverable “just city” seems to infer the duty to impose such a schema onto others, willing or not. In direct contrast, the “Realism and Restraint” school is often linked with ideologies of amorality or isolationism. “Just leave me alone and let me grill.”

Both of these caricatures are foolish simplifications. In reality, both approaches share a moral foundation rooted in prudence (phronēsis), the classical virtue of doing the right thing in the right way for the right reasons.

As Thomas G. West notes in his superb 2004 essay “Leo Strauss and American Foreign Policy” for the Claremont Review of Books, Straussian foreign policy emphasizes self-preservation and domestic excellence over missionary expansion. My contribution adds this insight: Straussian foreign policy aligns naturally with a realism-and-restraint platform. Both are concerned not just with survival, but with the flourishing of the American citizen. They do not simply see the world as it is, but limit action to what prudence and justice permit.

A truly Straussian foreign policy is realist in understanding and restrained in action, because it recognizes that both domestic and international politics are governed by the tragic limits of human wisdom and the necessity of prioritizing one’s own polis. These limits and priorities demand that the United States conduct foreign policy that is prudent and aimed at preserving the good life of its citizens, not the universalization of its ideals through endless military campaigns.

Bleeding Out

As a governing principle, restraint is the idea that the United States should pursue goals only that directly protect or benefit the American citizenry. This is not a notion of vague American “interests,” which could include those of multinational corporations, stakeholders, trading partners, or even allies. True restraint only seeks to serve the American people, a self-limiting inclination that has many benefits. It focuses the punch while limiting our exposure to blowback.

In classical terms, restraint is the statesman’s version of temperance. It recognizes that action divorced from limitation can devolve into tyranny. Without limitation, the lines between needs and favors, between wisdom and greed, blur. The American Founders understood this, as they did not believe in a state of permanent entanglements or the global exportation of democracy. Washington’s Farewell Address regarding these points is well-worn ground, as is John Quincy Adams’s famous warning that America “goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy.”

Restraint is moral not because it hides from evil, but because it chooses to act on the existential danger at hand. It does not confuse the power to act with the duty to act everywhere, which has bled the American citizen dry and has brought danger to our shores, including the horrors of 9/11.

In his 1996 Declaration of War Against the Americans Occupying the Land of the Two Holy Places, Osama bin Laden condemned U.S. military bases in Saudi Arabia—home to Mecca and Medina—as an intolerable violation of Islam. He portrayed the presence of non-Muslim soldiers there as an act of sacrilege and argued that Muslims had a duty to expel them by force. This became the central grievance in al-Qaeda’s ideology. You don’t have to agree with that linkage—I certainly do not—to recognize that it supplied a justification to carry out carnage.

The cost of all the U.S.’s wars abroad since then is approximately $8 trillion, or about $30,000 for every U.S.-born citizen. Was that in response to an existential threat? Certainly, retaliating against al-Qaeda and pursuing bin Laden were—but that was just a tiny fraction of the trillions spent, which led to a trail of destruction and ignited hatred for the U.S. in its wake. Iraq is now Shia. Libya is a civilizational disaster. Iran is in the arms of the Chinese. And Afghanistan is in the hands of the U.S.-equipped Taliban.

Constrained by Wisdom

In his CRB essay, West argues that Leo Strauss viewed the health of a political community as its first moral obligation. Strauss saw that “foreign policy must begin with concern for the integrity of one’s own regime,” not with the ambition to reform others. West notes that Strauss’s teaching on natural right directs attention to the inner structure of the political community. That is, its virtue, order, and capacity for self-rule are the telos rather than pointing to universal moral projects abroad. This emphasis reinforces the realist-and-restraint position: the defense of the American way of life, not the export of it, is the proper aim of statecraft.

West writes,

The Athenian experiment with indefinite expansionism was doomed (among other reasons) by a simple fact, which the Athenian leaders after Pericles failed to recognize: “it is in the long run impossible to encourage the city’s desire for ‘having more’ at the expense of other cities without encouraging the desire of the individual for ‘having more’ at the expense of his fellow citizens.”

The Athenians did not see, as Socrates did in his recommendation of the “noble lie” in the Republic, that an expansionist foreign policy is bound to undermine the political order at home.

If U.S. foreign policy had been cabined by the rubric of “restraint,” both then and now, American citizens would undoubtedly be better off. Phronēsis calls us to the wisdom to restrain our collective action to that which directly protects or benefits the American citizen. Without this focus, citizens are eventually incentivized to turn against each other, which is hardly an example of a “just polis.”

Realism begins with the tragic anthropology that Strauss illuminated and shared with Thucydides and Machiavelli—that is, human beings are not angels. In a Judaic and Christian framing, they are subject to the fall. Since states are composed of fallen men, they act from self-interest. Realism understands that foreign entities pursue their own good. How they perceive this good is shaped by their history, geography, and regime type.

Let me interject here that Strauss rejected a raw historicism. His view was one of maturity, one composed after escaping the cave. We cannot expect this of all state actors. While capital T Truth is universal, its global achievement is eschatological. It is not immanent, and cannot therefore be expected to be grasped by all, or even be capable of being comprehended by all, in a fallen world.

Consequently, the realist recognizes that the United States cannot itself transform these interests, but can only respond to them. It can function as a beacon of what is good, but not always as a hammer to strike what is bad. Again, as West states, “In sum, the classics’ ‘realist’ conception of foreign policy is ultimately justified only insofar as it serves their ‘idealist’ conception of domestic policy.”

The realist must also act in recognition of his own country’s capabilities and capacities. A 50-year-old man wisely does not challenge an Olympian sprinter to a 100-meter race, though perhaps the older man could compete in a different venue. The United States was once the lone hegemonic superpower, but the days of no-peer or near-peer adversaries are over.

America First

Was Strauss’s defense of the West a global project of Enlightenment democratization? His statement from Natural Right and History that “The political things are those that men can decide, and different men can decide differently” indicates the answer is a resounding “no,” despite what some of his students later espoused.

As Strauss wrote in the essay “The Crisis of Political Philosophy,” “The experience of Communism has provided the Western movement with a two-fold lesson…a lesson regarding the principles of politics. The practical lesson was that ‘for the foreseeable future there cannot be a universal state, unitary or federative.’” Even his teaching on esotericism presupposes a uniqueness of reader impression, based upon time and place, which is an implicit rejection of neoconservative extremes.

The first duty of American foreign policy is not to spread enlightenment, nor to redeem the world through our ideals, but to secure the flourishing of American citizens. A republic exists for the sake of its people; its moral horizon is defined by their safety, prosperity, and the conditions of a good civic life. To act beyond that horizon, except in cases where the nation’s security or integrity is directly at stake, is to mistake zeal for virtue.

Realism, rightly understood, disciplines the statesman to see the world as it is. It strips away the flattering illusions of moralism and sentiment, revealing the persistence of power, interest, and character in human affairs. It is not cynicism, but clarity—the recognition that each nation, like each soul, seeks its own good, and that wisdom consists in discerning the limits of one’s ability to alter those ends.

Restraint complements this vision by governing the manner in which power is used. If realism teaches that we must see clearly, restraint ensures that we act justly. It channels strength through prudence so that action serves necessity rather than appetite. Together they form what might be called a patriotic ethic of responsibility: the conviction that a republic’s first moral task is to protect its people, not to evangelize ideology abroad.

In this sense, restraint is not a retreat from moral duty but its fulfillment. It recognizes that virtue in politics depends upon proportion. May the U.S. via its leadership do the right deed, in the right measure, at the right time. The Straussian idea of civic virtue points precisely in this direction. The best regime is not the one that conquers the most territory or converts the most minds, but the one that orders itself toward the good of its citizens. Empire dissipates virtue; self-government cultivates it.

The moral paradox of restraint is that it alone preserves both liberty and virtue. For by accepting the limits of power, the restrained nation guards the very moral order that power exists to defend. Not all good things can be done by force, and the wise statesman knows that the preservation of freedom often depends on the refusal to wield it boundlessly.

The true statesman, like the philosopher of the ancient world, knows that order begins at home and that power without discipline corrodes what it means to be free. Lincoln understood this when he tempered his realism with charity, seeking not conquest but restoration. Washington understood it when he urged the young republic to let reason rule over passion and to avoid the intoxicating vanity of empire. Both saw that the health of a people depends not on the reach of its dominion but on the integrity of its soul. To recover that wisdom of uniting strength with restraint and clarity with humility is the moral task of American statecraft in our time.