Building N52 sits across the road from a beat-up Sunoco gas station at a dusty, busy intersection in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Inside there is a long, dark corridor and at the end, a door marked by a sign with just four letters: T-M-R-C.

The room beyond is large, cluttered, with a low ceiling, and, in most ways, looks like a university engineering workshop. But there’s one extraordinary feature: an enormous chest-high table that runs the entire length of the room. On this table are sweeping hills, a lumber farm, a town with shops and offices, and a papier-mâché mountain. And winding through all of this, chicaning past a church and finally ending at a depot, are tracks. Lots and lots of train tracks. This is the Tech Model Railroad Club of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The student society started as just the Model Railroad Club. But then in the late Fifties, down the hall came wheeling two huge, fragile, ridiculously expensive and towering machines: the TX-0 and the PDP-1. And it was from this club — with what you can only imagine was startled wonder — that the first undergraduates in the world got direct, face-to-face access with computers.

Up until this point, computers had only ever been housed in the starched, controlled world of military laboratories. Access to computers was tightly limited and normally possible only via specialist technicians. You could never actually touch the computer yourself: you would hand a stack of punch cards to the technicians who, some hundreds of hours later, would give you the result of your programme. But the members of the TMRC didn’t have to worry about such bureaucratic control. ‘‘There was no such thing as a computer club,” John McNamara, who joined the TMRC in the early Sixties, told me when I paid a physical visit to the club some years ago. “Step out of here and step to your right. That’s one of the birthplaces of American computing.” As humans and computers began to interact, something incredibly important began.

Some TMRC members approached computing with a kind of monastic devotion. Scruffy, dishevelled, and almost exclusively male, they would stay awake through the night for the chance to get in front of the computer and get down to programming. They were also, at times, smelly: body odour was measured in “miliblatts”, named after one of the TMRC’s most legendary hackers, Richard Greenblatt. This was a new culture, with its own language, and in-jokes. To “munge” something was to “Mash Until No Good”. To “gronk” an item was to destroy it. “Losing” code was ugly and inefficient. “Winning” code was the opposite. But one word has lived on more spectacularly than any other: to hack.

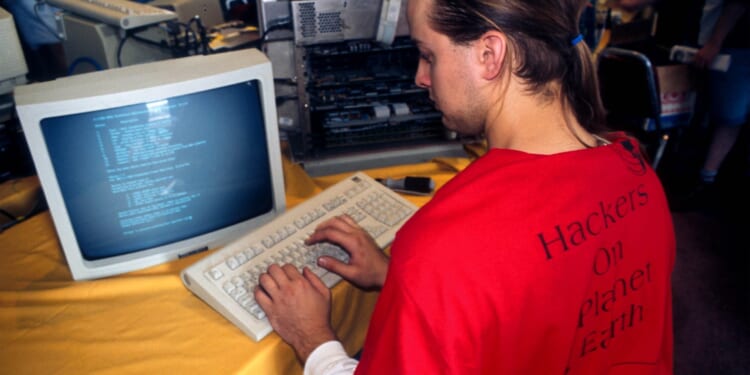

Today, hacking is often considered to be synonymous with illegality. Think of the cliché of the hacker: a man, wearing a black hoodie, coding ones and zeros, for some reason green, into a computer. His face is probably covered by the shadows of a darkened room. But that image is far from what the word “to hack” actually means. In the TMRC, “hacks” were computing achievements that combined technical mastery with a sense of creativity, fun, even whimsy. The first computer game, Spacewar!, would have been considered a hack by the people who wrote it. The early hackers created a programme that would instantly convert Arabic numbers to Roman numerals. Why? Simply because it was difficult to do. They also computerised the timetable of the the Tech Model Railroad itself; surely the first railroad in the world to join the digital age. This was the birth of the hacker mindset that thrilled in making computers do things no one had done before. Hacking was not necessarily illegal, but it wasn’t necessarily rule-following either. “Lock hacking” was developed so TMRC members could break into the computer at night. The old world of inefficient bureaucracies, clunking hierarchies, and — yes — formal rules didn’t understand computers, and so was to be largely discarded.

“Scruffy, dishevelled, and almost exclusively male, they would stay awake through the night for the chance to get in front of the computer and programme.”

As charted in Stephen Levy’s definitive account Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution, the hacker mindset that began in that dusty model railway club has stretched and evolved over time. By the 1980s, hacking’s centre of gravity had shifted coast to San Francisco and the Bay Area, with groups like the Homebrew Computer Club hosting hackers not just writing code but tinkering with personal computers and electronics. Things became bigger, more commercial and some hackers shed some of the counter-culture of previous years, and thence, hacking created the richest men and largest companies in the world. Before it was renamed, Facebook’s address was 1 Hacker Way.

Nowhere is it clearer what hacking now is, what it has become and how it has grown since the days of the TMRC, than on one summer weekend in the Nevada desert. Once a year, hackers descend on Las Vegas in their tens of thousands to attend Defcon, the largest gathering of hackers in the world. There you’ll spot a cluster of bright blue mohawks, plenty of blockchain tattoos, and code jokes printed across black T-shirts. While less nerdy and introverted than the TMRC, today’s hackers are effectively doing the same thing: lock-hacking, sharing code, and delighting in the art and mastery of the best hacks.

The hacks on display at Defcon are astonishing. I have seen laptops hacked with light. I have seen hackers peer into secret instructions that have been written inside processing chips. Someone once explained how they could cause wind turbines to explode. Another showed a crowd how to make lifts go up to unadvertised floors. And then, I’m embarrassed to say, I’ve been hacked myself. In what I can only describe as 10 seconds of crushing naiveté, I pulled my credit cards out of a protective pouch to buy a bottle of water in the oppressive heat — only to come home to see a dozen Uber Eats orders had been placed.

The convention floor is always a curious place. Intermittent cheers can be heard against a constant techno soundtrack. This year, one burly, tattooed hacker bellowed “hack the world” from the stage. He later told me he worked in the Supreme Allied Shenanigans Division. The room, lit up by neon signs, is littered with dozens upon dozens of competitions. In the Beverage Cooling Contraption Contest, teams compete to chill a drink in a red cup as quickly as possible. Then there’s a fiendishly difficult contest which involves cryptographic puzzles scattered online and physically across the room. An anonymous team of furries collected their prize wearing animal masks — they’ve won that competition every year. Running around the convention floor are those who organise Defcon. They wear only red and go by the name “goons” — the origin of the word, like many things at Defcon, is the product of some long-ago in-joke.

The only rule is to absolutely not film the crowd. Otherwise, almost anything goes. Most attendees turn up with $500 and nothing else: no name or registration needed. Some wear masks the whole weekend. But there are also police lurking on the convention floor. One person tells me to look out for people wearing Pikachu hats because they’re from an intelligence agency. Another flashes me his military police badge.

What binds hackers across social divides, political chasms, and even both sides of the law itself is a particular mindset. Hackers fundamentally believe in computers — in access to them, the power of them, and their capacity to improve our lives. They mistrust authority and hierarchies, but also do not trust locked doors, black boxes, hidden code or anything else that might be used to control them — they will go to extraordinary lengths to break them open. Above all, they revel in the art of the hack: they have come to see technical mastery as a very human act of self-expression and creativity.

Hacking, though, isn’t just fun and games. Scientists sometimes perform “biohacking”, where they apply the same hacker ethos to questions of human implants, sensory augmentation and smart drugs. It has also become intertwined with geopolitics. “Making Putin mad since 2014,” said Ukrainian hacker Alex Holden at this year’s Defcon. Holden has been locked in a digital duel against a Russian cyber-criminal group called Killnet that sometimes works on behalf of the Russian state. For years, Holden and Killnet have tried to track, infiltrate and expose each other. Holden finally managed to identify its leader as the former drug dealer Nikolay Serafimov, hack a Russian drug market central to Killnet’s operations, and finally cause the group to disband.

But even among hackers — people whose very identity is wrapped up in technology — the shadow of AI automation is looming. Some of the competitions this year anxiously explored the increasing capabilities of AI agents. In fact, the first thing I saw at Defcon this year was a team of college-age hackers picking up a giant $4 million cheque for a competition to train AI to identify vulnerabilities in code. The organisers of the contest — the US federal agency Darpa, inventors of the precursor to the Internet in the late Sixties — deliberately introduced the defects for the AI to find with no human intervention. The results were staggering: not only were the models brilliant at finding the introduced vulnerabilities, but they also found real ones in code that millions of people use every day, and that no one had ever noticed. “The world changes today,” said a man standing on a huge stage, facing thousands of people staring back at him.

Matters such as cyber-security and online privacy will ultimately be determined by duelling mathematical models. AI, used by both attackers and defenders, will race across millions of lines of code, in desperate search for vulnerabilities to either plug or exploit. This isn’t necessarily bad news, by the way; it may well be that AIs dramatically benefit defenders over attackers. But it will make these sorts of conflicts more inscrutable and shadowy to all of us who don’t spend our lives thinking about them.

So will hacking itself be swallowed by AI? Well, it is no accident that the TMRC hackers, as really the first computer club in the United States, became the core of the first group devoted to studying and building artificial intelligence. Naturally, they saw, before anyone else, that computers were more than expensive number crunchers. Lurking in the machine was, the hackers probably felt as much as knew, the potential for machine intelligence. And there is something fitting how, 60 years later, the descendants of these early computers aren’t just getting hacked; they’ve become hackers too.