Held in late February or early March, the Geneva Motor Show used to coincide not only with the automotive industry’s start-of-year giddiness, but also with Switzerland’s best snow. Pre- and post-event ski trips were part of the occasion. Corporate hospitality teams from automotive companies of all sizes would bookend the press preview day, when manufacturers would reveal to the world’s media their upcoming models for the year, with boozy, drawn-out jollies for favoured consumer journalists.

It was a vast and lavish operation. While roadies were building manufacturers’ elaborate show stands in the 26-acre Palexpo centre on the run-up to the event, their PR counterparts were turning the region’s resorts into a multi-week, multi-Alp industry bacchanal. Immediately after the grand opening night, the sector would decamp in its entirety to money-no-object afterparties at chalets, hotels, and rented pleasure craft in the Petit Lac.

Like the rest of Europe’s car industry, it was fun while it lasted. And also like the rest of Europe’s car industry, it “lasted” about a century before the wheels came off. As Covid-19 tore through Europe, the show’s organisers cancelled the 2020 edition at the last possible minute. It was a panicked decision that infuriated exhibitors, many of which had spent seven-figure non-refundable sums preparing enormous displays for which the show had become known.

The show disappeared for a few years, returning meekly and to a tepid reception in 2024, but by then European carmaking had begun to change the way it imagined itself. China, Covid-19, Dieselgate, EVs and Net Zero all cast a shadow over the Geneva Motor Show and the fossil-fuelled success it represented. Footfall had plummeted from over 600,000 punters pre-pandemic to about a quarter of that at the show’s half-hearted final Swiss instalment, which was largely snubbed by even large car brands that couldn’t justify the cost of appearing, and which had been rattled by several years of supply chain issues. An attempt to rebuild the event’s prestige in Doha fell predictably flat and, as the wider industry reckoned with its new, challenging headwinds, the organisational committee moved to dissolve itself, marking the end of one of Europe’s most influential industry showcases. It was simultaneously a regrettable circumstantial fumble and a helpless industrial self-own.

If Geneva’s death reflected a symbolic fracture in Europe’s century-long automotive home run, the rise to prominence of the Brussels Motor Show — a more straightforward, pragmatic and frankly dowdier occasion — reveals its current crisis of self-esteem. Held a little earlier in the year, the Brussels event has pretty much inherited Geneva’s position as Europe’s de facto auto show of note, now hosting the European Car of the Year awards and a smattering of product unveilings, but without any of the glamour. Journalists and dignitaries visiting this year’s rainy press preview day were greeted by buckets, some filling with alarming speed, placed beneath the numerous leaks in the elderly Brussels Expo roof.

The rot can, by my reckoning, be traced back to Q3 2011. When I first started writing about vehicles in 2009, the Chinese automotive industry was justifiably disregarded in Europe. Nobody drove an electric car. Only 55 EVs had been sold in Britain that year, compared with around 600 across the rest of the EU. Europe’s entire EV fleet could, at the time, have parked several times over in the car parks of Belgium’s leading exhibition centre. But within about 20 months, Nissan had launched the Leaf (arguably the first mainstream EV) and the Chinese state-owned giant SAIC had begun selling the sub-par MG6 saloon, laundered for the British market with the historic MG badge. Both cars were bad in their own ways, but their arrival was the beginning of the end of Europe’s car manufacturing primacy. Fifteen years on, a British family is about as likely to choose a Chinese car as it is a Japanese one, and the country now buys those 55 electric vehicles by about 10am on a given Saturday morning. Some 9.7% of cars sold in Britain, for example, are from Chinese companies, and many more — especially electric models — were built in China on behalf of foreign ones.

My crumpled fold-out floor plan of the Brussels Motor Show charts this phenomenal pace of change. Mitsubishi’s stand is flanked by Chinese newcomers Jaecoo, Omoda and Zeekr, the latter a Geely sub-brand now headquartered in Volvo’s hometown Gothenburg. Opposite them is Xpeng, then Nio, then BYD — a company that only began exporting EVs five years ago, and which is now the world’s largest builder of them. Chinese car manufacturers are unambiguously okay now, having overcome some or most of the consumer scepticism they were met with when they first arrived, and are exploiting their considerable head start in EV manufacturing (which equates to around half a decade, or roughly one model cycle, particularly in battery and powertrain tech) and low production costs, which are estimated to be around a third cheaper than those of the European manufacturers.

This asymmetry is evident even on ostensibly “European” stands. The Spring, a cheap electric runabout sold by Romanian Renault subsidiary Dacia and occupying quite a prominent place on the brand’s display, is built in Hubei province. Smart (originally developed in the Nineties by Mercedes-Benz to sell microcars, which it built in its then-futuristic Smartville factory in Hambach) is now a German-Chinese joint venture that manufactures electric SUVs in Xi’an. Even the electric Mini Cooper, a direct descendent of, arguably, British carmaking’s greatest cultural export, is now built in Zhangjiagang.

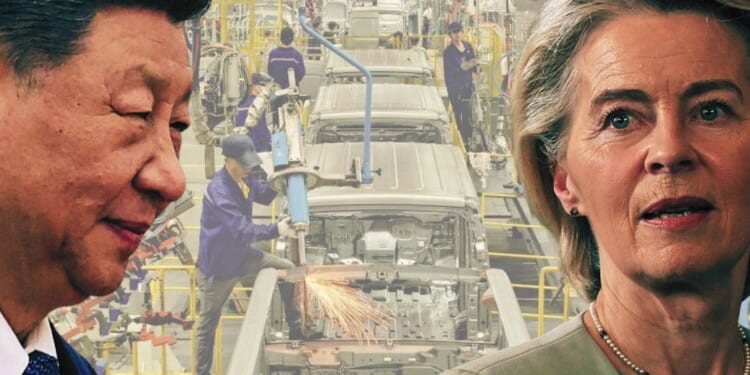

Regulators, half an hour away on the Brussels metro, and politicians, 20 minutes away by diplomatic S-Class, have consistently encouraged and rewarded these incursions. They have cajoled consumers towards EVs that only Chinese companies can sustainably sell at anything approaching affordable prices. And the Chinese government, which has created near-chaotic levels of oversupply in its neo-dirigiste car and battery industries, and which has identified global leadership in this critical sector as a strategic ambition, owns companies that are increasingly able to participate directly at the consumer level rather than merely embedding themselves into global supply chains.

To put it politely, this challenges conventional narratives of European automotive supremacy. Longstanding manufacturers from industrial powerhouses like Germany and France — frequently downplayed as “legacy brands” with varyingly scornful undertones — were the best in the world at building petrol and diesel cars. Audi’s Vorsprung durch Technik slogan reflected a national ideology during the internal combustion era, while Renault’s pre-war l’Automobile de France became a macroeconomic truth as its automotive engineering grew integral to its industrial output. Carmakers were relevant to cultural identity as well as GDP, and as tangible representations of homegrown technological prowess, passenger vehicles are perhaps more obvious to a major nation’s population than, say, its arms or chemical products. And to smaller European countries, which entered the car sector late, the mass production of quality consumer vehicles grew to represent an economic ascendancy beyond agriculture, raw materials and whichever less aspirational heavy industry they had been involved with previously. When Škoda Auto was privatised and integrated into Volkswagen in 1991, the confidence signal (and flow of Deutsche Marks) changed the way post-communist Czech manufacturing was perceived both internationally and at home, and the country’s automotive sector is now its industrial flagship and major source of national pride.

Tucked away behind the beefy six-figure EVs at the Brussels show are a smattering of perfectly good, conventional, small-displacement petrol cars, with manual gearboxes and realistic prices. Still in production for the next few years at least, these are living artefacts of an era in which Europeans built their own stuff. China was among the worst at manufacturing this kind of car, never coming close to emulating Europe’s internal combustion engineering, which was of such undisputedly high quality that it deterred new entrants. In the Net Zero era, that polarity has begun to reverse. It’s little surprise that Europe’s routed giants are retreating into nostalgia.

Above the Alpine stand, a vast screen displays, on an endless loop, the brand’s short film entitled 70 Years of Lightness, which imaginatively intersperses live action clips of the French company’s historic models racing on a mountain with stylised Ligne Claire animated sections, redolent of Hergé’s (locally) legendary Tintin cartoons. Mercedes-Benz’s sprawling display includes a replica of the Patent Motor-Wagen, probably the world’s first car, which it claims as its spiritual origin. Lotus has seemingly painted its Evija hypercar in John Player Special livery in a wistful nod to its own self-nominated motorsport heyday. But the retrospection has seeped even into the physical designs of Europe’s current and next-generation models, which increasingly lean on yesteryear’s fondest memories.

On the Renault stand, for example, rehashes of the R5 Turbo (a mid-Eighties “hot hatch” motorsport pinup) and Renault 4 (the first modern hatchback, mechanically speaking, with 8 million sold worldwide over three decades) sit beside the new Twingo, which revives both the nameplate and the cutesy bug-eyed design of the 1992 original. Behind the new but retro-styled Panda on the Fiat stand is the new Trio, which directly apes postwar trikes like the Piaggio Ape that were a cornerstone of Italian transport for half a century. There’s nothing fundamentally new about car manufacturers referring back to their greatest design hits — an ever-present reminder of this is the 2007 Fiat 500, which did for 21st-century Fiat what the original Cinquecento (on which its design is based) did in the nascent post-war economy of Fifties Italy. But short of a pan-European miracolo economico, these reheated people’s cars risk coming across as an expensive pastiche.

“Short of a pan-European miracolo economico, these reheated people’s cars risk coming across as an expensive pastiche”

Almost all of Europe’s largest mainstream car companies owe their existence in the market — and status as flag-carriers for their home country’s economy — to an affordable mass-market “people’s car” that they sold at some point in the 20th century. Famous examples include the Citroën 2CV, a simple peasant-spec machine originally slated for a 1939 launch, but ultimately released into the wreckage of rural France a decade later; Fiat’s aforementioned 500, designed to fit inside the twisting streets of Italy’s borghi, both symbolised and facilitated the mass mechanisation of postwar Italy; and Volkswagen’s Type 1 Beetle, a design so good that it remained in production until 2003, remains the bestselling single product in the industry’s history. Even later models like the Renault Twingo (totemic of Europe’s now-lost belief in compact, inexpensive cars) and Renault Espace (which spawned the “Eurovan” genus of aggressively practical people-carriers that dominated motorways for 20 years) responded neatly to the needs of Europe’s economy and citizens at the time.

It is likely that any modern-day equivalents will be Chinese-developed or Chinese-built using Chinese components or at least Chinese raw materials. Europe’s remaining car industry, underpinned anyway by Chinese supply chains, has been forced to relinquish its century-old relevance to ordinary Europeans — a hard-won privilege deftly undermined over just 15 years. Today, the capacity to deliver affordable cars that Europeans either want or are forced by regulations to need belongs exclusively to foreign manufacturers, predominantly Chinese.

Volvo belongs to Geely, as does the manufacturer of London’s black cab. German-owned Mini builds its British-flavoured EVs in Jiangsu province. Stellantis, headquartered in Hoofddorp, owns formerly patriotic brands like Alfa Romeo, Fiat, Peugeot and Maserati, as well as selling Chinese-made Leapmotor runabouts that substantially undercut most alternatives. The historic giants that once dominated the Geneva Motor Show through superior engineering and cultural cachet have, in the years since the event imploded, either been consumed by Chinese corporate might altogether, or forced to consolidate. The smaller, damper Brussels Motor Show is where the wounded survivors have rallied.

Europe will find it difficult to un-strip the assets of its former industrial keystone. With zero-emission mandates funnelling consumers and commercial buyers towards what is effectively an imported technology, it is near-impossible to imagine a solution that meaningfully rectifies the auto sector’s current course. Tariffs have proven ineffective at stymying the influx of Chinese cars, which now enjoy a 12.8% market share. Manufacturers are happy to swallow the additional costs, and Chinese suppliers are beginning to open plants in third countries anyway.

At the last-ever Geneva Motor Show, former Renault boss Luca de Meo called for what would amount to an Airbus-style consortium of pan-European cooperation on affordable electric cars, a further dilution of carmakers’ national identities and still a slightly unconvincing response to China’s heavily subsidised and comprehensively integrated supply chain. There are doubts as to whether Europe could come close to emulating this raw materials advantage, even in favourable regulatory conditions or if a coherent decision was made on reducing reliance on EV imports. In all but the most optimistic of scenarios (which involve the rapid exploitation of local mineral deposits and the development of advanced industry to process them) Europe’s car sector, and by extension the mobility of its population, will be in Chinese hands.