In the 2010s it was commonplace to hear that such-and-such a prominent woman had “imposter syndrome” — meaning she went through life irrationally feeling as if she was about to be unmasked as a fraud. It seems that the disease goes all the way up to national leaders. In Nicola Sturgeon’s autobiography, Frankly, published yesterday, she describes suffering from it too. “The better I did, the more of an imposter I felt, and the greater the fear of being ‘found out’,” she writes.

Ploughing through the early sections of the book, I started to understand the worry. There is certainly a startling mismatch between the former first minister’s famed communicative abilities and the descriptions on the page. For instance, if there’s one thing our author wants you to know, it’s that she loves books. The point comes up time and again: as a child, she was “bookish”; “rarely had her nose out of a book”; had a “fascination with words”. Early on, she became “immersed” in Jane Austen, Robert Louis Stevenson, Sir Walter Scott. Later in life, no doubt thanks to all that reading, she describes herself as having the power “to communicate in a way that engaged both heart and head” and to understand “the importance in politics of telling a compelling story”.

But why, then, are her anecdotes from her childhood so plodding and banal? That time when she went to the “retail metropolis of Ayrshire” (i.e. Ayr), and her parents wouldn’t buy her a coveted Cilla Black record, but then… her grandad bought it for her instead. That time when her teenage boyfriend Sparky broke up with her: “it’s not impossible that in different circumstances we would have ended up together. Whether we would have lasted is another matter.” Even seismic events become comically flatfooted in her retelling: “It was from Uncle Dave that I first learned about death. He was thrown from a horse and killed during the annual Laminar (sic) Day celebrations in his hometown of Lanark.” So peremptorily and colourlessly does she rattle through various friends and acquaintances, it is as if she is ticking them off from a list.

An optimistic reader might suspect she is getting the boring stuff out of the way so she can get to the moment when life properly began: the fateful day when, aged 16, she knocked on the door of her local SNP candidate’s house and offered to help with canvassing. But even during the sections recounting her formative years as a political operator in a then up-and-coming party, narrative excitement remains elusive. For instance, the highlight of the 1989 Glasgow Central by-election, as far as she can recall, was a nightly “protest” — quotation marks hers — waged with her pal Shona against sexist bartenders at the Laurieston pub. “Every night after campaigning, we would perch ourselves on bar stools and loudly demand to be served, usually to no avail, leaving us to drink pints bought for us by our male friends instead”. Compared to this, Theresa May’s “running through fields of wheat” admission starts to look like glamorous juvenile delinquency.

Still, by the time we get to the heart of the story — that is, an allegedly unguarded recounting of the period between becoming deputy first minister in 2007 and her eventual resignation as premier in 2023 — there is some evidence that reading Robert Louis Stevenson has left its mark, however unconsciously. For a bit like Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, there appear to be two different people battling within the breast of this book’s protagonist. Indeed, Sturgeon is sometimes herself aware of the tension: as when, in a climactic moment just after she has been made first minister, she describes listening to conference applause, and feeling “a sort of dissociation” between “the shy, dour, always self-doubting, frumpy girl… in the wings” and the “confident, articulate, almost stylish version of herself… [on] the stage”. Along with some readers perhaps, she wonders: “Who is that woman? Is she real?”

There are other, less self-flattering, dissociations evident in the book too. Its narrator keeps implying she is good at empathy and warmth; that she has been able to forge a “deep, almost emotional, connection… with a sizeable swathe of the Scottish population”. Certainly, that is her public reputation. But warmth is in the showing not the saying, and there is little on show here; only robotic expressions of sadness and shock at various significant deaths and tragic events, before getting onto the more important business of how they might affect ongoing political manoeuvrings. Similarly, the official version of Sturgeon is admirably high-minded and principled, and particularly on behalf of women and girls. Constantly monitoring for the potential presence of misogyny, she can’t describe accepting a bunch of flowers from Govan trade union officials without noting “a touch of unconscious sexism in the gesture”. Yet at another point, she ruthlessly criticises Labour leader Jack McConnell for having eschewed cheap sexist vibes and treated her with respect instead, describing his personal kindness to her as “naïve politics” and a “huge tactical error”.

“Another mystery is why Sturgeon is a nationalist at all.”

Another mystery is why Sturgeon is a nationalist at all. Her main reflections on the question are that in 1987, when she first joined the SNP, the party was more of a natural home for her youthful socialist politics than Neil Kinnock’s Labour. Given the strength of social conservatism in the party back then, this is implausible; but more importantly, it is also underwhelming as a justification of her life’s work. Where are the traditional tartan romances, the misty-eyed misty glens, even just some memorised lines from Braveheart?

Her avowed heartfelt desire for Scottish independence is certainly not due to any deep knowledge of her country’s history: the occasional forays into this territory sound heavily mined from Wikipedia. It doesn’t seem to be informed by political theory either: there are no detailed discussions of the ideals of democracy or sovereignty here. It is clear Sturgeon loves Scotland; who could doubt it, faced with a sentence like: “Standing on the shore, looking out at Ailsa Craig — the uninhabited island about sixteen kilometres west of the mainland, home to puffins and gannets, and from which microgranite is quarried to make curling stones — still gives me a sense of peace and tranquillity that I don’t find elsewhere”? But still, as she occasionally acknowledges rather grudgingly, many Unionists love their country too.

In Stevenson’s novella, Mr Hyde kills an elder father figure; and in a way Sturgeon does the same. The passages describing her complex relationship with Alex Salmond are among the book’s most engaging, though bound to infuriate his supporters. Whatever the truth of her involvement in the investigations he faced for alleged sexual misconduct (he was eventually cleared of all charges) — she says she had none — it is clear that she had to get out from under the charismatic politician’s spell to become the leader she did.

She owed much of her initial success to him, and she knew it: he plucked her from the crowd to serve as his deputy, which led seamlessly to her becoming first minister after he resigned. At the same time, he was everything she was not — a witty, risk-taking gambler, big on charm and low on detail — and the fact obviously annoyed her intensely. Her infuriated tale of writing a crucial White Paper during the highly pressured referendum period, then fielding a phone call from her boss at the racecourse, tipsily promising he would definitely read it before the big launch, will resonate with every i-dotting, t-crossing female employee ever faced with a slipshod superior.

Sturgeon’s own approach was very different: obsessing over minutiae, micromanaging underlings, staying up all night fretting nauseously about how things might go wrong. This seems to have worked well during her time as health secretary: when she was set clear objectives, she was all over her brief (at least, as she tells it). But once put in charge of overall goal-setting as first minister, she seems to flounder. Unable to bring about a second independence referendum, and apparently devoid of concrete ideas to deal with Scotland’s overwhelming social problems, she adopts a generic, vibes-based playbook and hopes for the best: some renewable energy and child welfare here, a bit of gender reform there, free university tuition fees all round. When Covid hits and she is able to return to full technocrat mode, you can sense her relief, even if the huge responsibility nearly breaks her.

But here, too, there are significant omissions. Despite her professed concern for children stuck in poverty, she offers no reflections about how lockdowns might have grievously affected them, making a bad situation even worse; nor about how social isolation might have led to a generation of unhappy teenagers falling deeper into an online world. And speaking of which: in the end, the gender reform thing didn’t work out so well either, indicating another puzzling split in the Sturgeon psyche.

Early on in the book, she tells readers, perfectly accurately, that “building common ground isn’t possible without compromise” and that “it is always a good idea to know your audience”. Yet in practice, Sturgeon ploughed ahead obtusely with plans to reform gender recognition processes along self-identification lines, deaf to reasonable objections, and blind to the way her stance would be perceived by ordinary voters. By the end of the book, discussing the fallout from the Isla Bryson scandal — which saw a rapist heading to a female prison because he said he belonged there — the bad-tempered, stubborn version of Sturgeon seems to have vanquished the more politically astute one. Through gritted teeth, she attempts to admit to her own mistakes in this area, suggesting she should have “hit the pause button” on gender reform in order to develop consensus; but she still can’t help monstering her opponents at every turn. They are on the same side as Orbán, Putin, Trump; they stand alongside “raging homophobes”; they deny such facts with “brittle defensiveness” and “howls of outrage”.

Meanwhile, her attempted justification of her own position on the nature of womanhood is made even funnier by the fact she thinks it is “too technical” for people to properly understand: namely (drumroll) “there is no need for a man to claim to be a woman to commit acts of abuse or sexual assault” because “the threat to women comes from predatory, abusive and misogynistic men, not from trans women”. In other words, her new, post-Bryson assumption seems to be that, as soon as a trans-identified man becomes predatory or abusive, “she” ceases to be a woman — QED. Indeed, in a recent interview she has said that a rapist “probably forfeits the right to be the gender of their choice”. Ironically, this is a case of what is known as a “no true Scotsman” fallacy: the circular idea that “no true Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge” isn’t falsified by the sight of Hamish from Glasgow wielding the sugar spoon over his oats; because all this really shows is that Hamish from Glasgow is not a true Scotsman after all.

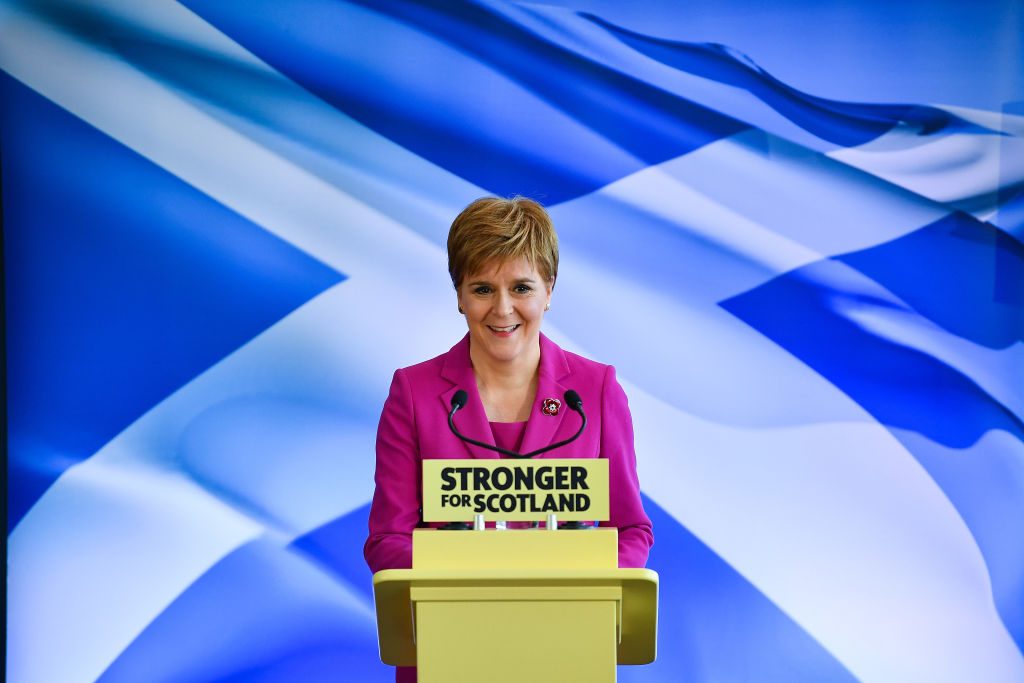

There was a time just after the 2015 general election, now hard to picture, when the wider world went mad for the progressive vibes Sturgeon was emitting, her party having just wiped Labour out north of the border. For a while, the first minister was mobbed and fawned over like a “rockstar” (her words) wherever she went — including by journalists in London. But looking back, it seems the whole thing was a comparison-based trick of the light: she looked more organised than Salmond, more authentic than Cameron, more effective than Miliband, more down-to-earth than Corbyn. Things got even easier for her in this respect when chaos merchants Johnson and Trump arrived.

But while she had diligence in spades, ultimately, she never made a dent in the most pressing national problems — rising drug deaths, falling education standards, terrible public health, violent crime in cities — and that’s partly because, in terms of her capacity to understand the bigger picture, her intellect was always too limited, tempting her towards the superficial gesture as a substitute. If Frankly is anything to go by, then, strictly speaking Sturgeon never did have imposter syndrome. To have that particular malaise, your nagging suspicion you aren’t really up to the task has to be wrong.