Weeks after the Trump administration arrested Venezuelan tyrant Nicolás Maduro, US officials are training their sights on a familiar next target: Cuba. Late last week, Trump issued an executive order requiring that any country supplying oil to the beleaguered island dictatorship face US sanctions. Reports now suggest that the Trump administration aims to depose the communist regime by the end of the year, and is searching for Cuban government insiders who can help cut a deal.

The administration’s reasoning is not merely that momentum is on its side, but that Maduro’s Venezuela — particularly its oil — had long served as one of very few lifelines available to a Cuban economy teetering on the edge of collapse. Now that Venezuela under Delcy Rodríguez has cut off that supply, an energy crisis is adding to an already bleak economic picture on the island.

By 1 January, two days before Maduro’s removal from Venezuela, Cuba had lost over 10% of its population over the previous five years. Over the same period, the country’s GDP declined by 11%. Around the country, Cubans are today frequently in the dark, owing not only to energy shortages but a disintegrating power grid. Cuba continues to sort through the rubble of Hurricane Melissa, which last October damaged almost 100,000 homes and much of eastern Cuba’s farmland, while the country also faces an epidemic of dengue fever.

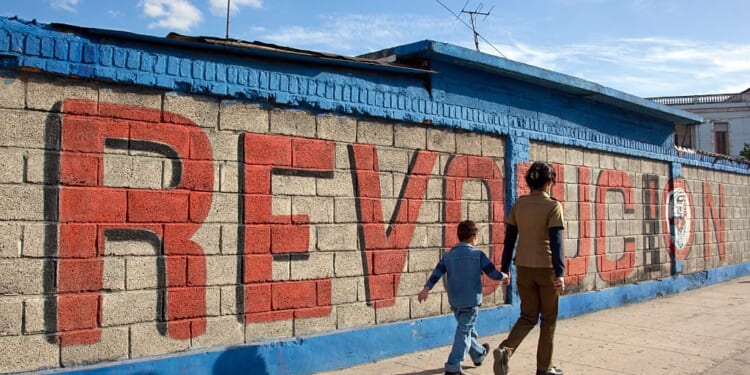

To topple the government of Cuba — one which has held its population to early-20th century living standards, repressed all political dissent, and been a thorn in the side of US policy for six decades — has long been an impossible dream for American presidents. Only two years after Fidel Castro and Che Guevara’s revolution, in 1959, President Kennedy failed multiple times to dislodge the new regime, whether by covert invasion force or assassination.

Eventually, the US settled on an indefinite extension of the 1960 trade embargo, a policy designed to ensure that if a longtime friend and ally of Washington was suddenly going to embrace a political ideology antithetical to American values and interests, it would have no support from American commerce in doing so. The policy, which has persisted to this day, succeeded in washing America’s hands of communist Cuba. It failed entirely, however, to pressure Cuba to pursue a different course.

The embargo’s failure would become synonymous with the axiom that one cannot starve revolutionaries out of their ideologies merely by disengaging with them. As both Cuba and the hermit kingdom of North Korea have shown, communist leaders can use their control over the flow of information to blame their citizens’ poverty on the very nations they have alienated, thus instilling an “us against the world” mentality that dulls the gnaw of poverty, keeps counterrevolution at bay, and preserves leaders’ power.

But even despots cannot ignore the needs of their people forever. After the Soviet Union’s fall in 1990 deprived Havana of a longtime source of international aid, Cuba’s GDP fell by a third. Its economy limped along for two decades. Desperate Cubans regularly left the island on unseaworthy crafts to seek asylum in America, in a manner reminiscent of the South Vietnamese “Boat People” of the Seventies. By 2010, Castro’s brother and successor Raúl was declaring that “we reform, or we sink”.

In the early 2010s, Cuba conducted a surface-level political and economic reform sufficient to convince US President Barack Obama to normalise diplomatic relations with the island in 2014, for the first time since the Kennedy presidency, in exchange for Cuba allowing American investment in the island. But over the years that followed, most of those investments went nowhere, waylaid by a command-and-control economy that government insiders still controlled. There was therefore little American political resistance when President Trump cut off diplomatic relations again in 2017. In 2021, Cuba experienced its widest-reaching anti-government protests since the 1959 revolution.

Today, Cuba — as a nation, a polity, and an economy — is at its lowest ebb since the collapse of the Soviet Union. With Fidel dead and Raúl retired, the family that held the Cuban communist project together is now gone. President Trump is right to see an opportunity. But to take advantage of that opportunity, he will need to bear in mind that Cuba is nothing like Venezuela.

For one thing, Cuba is a bureaucratic government with power diffused among a large group of party elites. President Díaz-Canel was hand-picked by Cuba’s Communist Party apparatus, and elected by a congress controlled by it. While Venezuela also has a congress, Maduro was a strongman elected by popular (sometimes rigged) elections. Because Maduro was the main locus of political power, a “decapitation” strategy of removing him from the country stood a chance of drastically changing Venezuelan government policy even as the rest of the government structure remained intact. In the few weeks since Maduro’s arrest, this does indeed seem to be happening. But in Cuba, there is no Maduro figure to remove. Power resides in Cuba’s Communist Party and its congress.

Another difference is ideology. Cuba is a one-party state. Venezuela, at least officially, is not. Venezuelan Chavists follow a populist socialist programme with considerable ideological flexibility, whereas Cuba is notorious for its legalistic interpretation of Marxist-Leninist communism. While both nations have always had their share of graft, Chavist Venezuela’s lodestar is self-enrichment for the politically connected, whereas Cuba’s is Marxism-Leninism, even when it impoverishes everyone.

And then there’s the question of historical memory. Whereas Venezuela was a functional democratic country within the memory of most Venezuelans, Cuba has been a communist dictatorship for as long as most Cubans have been alive. And even those few born during the reign of Cuba’s pre-revolutionary dictator Fulgencio Batista will find few lessons from that grim era.

Based on these contrasts, the Trump administration should instead base its Cuba policy on six decades of US experience with the country — as well as a century of experience with other communist regimes. These encounters might suggest that neither decapitation nor further economic sanctions are, in themselves, viable pathways to change in Cuba. An effective strategy, if it involves a stick in one hand, must be balanced by a carrot in the other.

“The Trump administration should base its Cuba policy on six decades of US experience with the country”

The most powerful carrot in our arsenal is the prosperity that comes from friendship with the United States. American strategy must make it painfully clear to Cuban leaders and citizens alike what they are missing by not being full members of the international community and the Western Hemisphere specifically. Today’s American leaders can learn a great deal here from the statesmen of the late Cold War, particularly men like Secretary of State George Shultz, who used Western economic dynamism to persuade the Soviet Union’s leaders essentially to legislate themselves out of existence.

Creating a functional democratic government in Cuba is going to require hand-holding. Cuba has been steeped only in communist political philosophies for the lifetimes of most Cubans. To learn anything else will take a great deal of external commitment. Cuba — like many other communist adversaries — also has a history of feigning reforms to attract concessions: as President Obama learned to his cost in 2014. To stick with the late Cold War theme, then, “Trust but Verify” will need to be the watchword of any US strategy toward Cuba, just as it was for Ronald Reagan and the Soviet Union.

Yet if the administration’s current strategy as widely reported, covertly convincing a critical mass of public officials to turn on the government is unlikely to work. If the Cuban Communist Party knows one thing, it is how to sniff out and imprison counterrevolutionaries. And even were this strategy to succeed, pandemonium would be the likeliest result in a nation that has known nothing but one-party rule for the better part of a century. Far better would be a policy that unequivocally shows an exhausted people the perks of friendship with the United States, and persuades them to leave communism behind. No coups required; a whimper, not a bang.

Trump’s first priority, then, should be to open the information environment in Cuba. An advantage here is Elon Musk’s Starlink, which could connect the whole island cheaply (or even, knowing Musk’s tendencies toward political philanthropy, for free). Reliable internet needs electricity, and Cubans are struggling with broken-down power grids. Happily, American firms have the dollars to help them rebuild. All Cuba’s government would need to do to receive these fabulous benefits would be to end online censorship. Were Cuba to do so and then go back on its word, meanwhile, those benefits could be taken away just as easily.

Once information is flowing more freely, the Trump administration should set to work on two initiatives at once — one economic, one political. First, Trump should work with US businesses to put together a massive package of potential investment for Cuba. In doing so, it should pretend to be living in a parallel universe with no trade embargo. It is difficult to overstate just how much American imports could contribute to the Cuban economy were the embargo to be lifted, even in part. One might compare Cuba to the Dominican Republic, a US ally with a similar population but which earns seven times as much export income as Cuba.

How might trade with the US uplift Cuba? Take the example of cigars. Cuba remains, in the estimation of most aficionados, the undisputed quality king. At the moment, though, Cuba’s total international cigar sales are around $1 billion. The country’s total exports, in all categories, are barely above $2 billion. The US market for premium cigars alone is $4 billion. Were American cigar smokers to choose Cuban cigars even half the time, US demand for Cuban cigars alone would equal the total exports of the entire island of Cuba. And that’s just cigars. Cuba also has some of the world’s best land for the cultivation of sugar and fruit, and some of the world’s largest deposits of nickel — a metal vital for producing electronics from phones to electric vehicles.

Once Trump puts together a suitably impressive list of hypothetical commitments, he can begin selling them to the Cuban government and its people. He could offer those investments individually, alongside matching abatements of the embargo, in exchange for specific political changes in Cuba. These could start with concessions in economic policy — allowing private businesses to compete with state-owned monopolies, for instance, or else setting exchange rates, tax policies, and legal frameworks to encourage foreign investment. As the economic rewards get bigger, meanwhile, Trump might exchange them for ever-greater political reforms ending, finally, with the abolition of Cuba’s one-party state, the freeing of political prisoners, and free movement between Cuba and the US.

Cuba is a once proud and vibrant country that has been hollowed by 65 years of Marxist-Leninist dictatorship. Rebuilding will take time, and such an ambitious programme might seem optimistic given the long decades of failure. Yet here it’s useful, perhaps, to return to Venezuela, which the US currently controls. Maduro’s regime was Cuba’s closest ally, and Havana is watching what happens in Venezuela very carefully. If Trump can prove that by bringing a longtime enemy into alignment with Washington, and is able to better the lives of Venezuela’s people, Cubans are likely to be far more receptive to similar ideas for their own country.

President Trump is an extraordinarily effective salesman, and this is fundamentally a strategy of salesmanship. The greatest obstacle to its success might be the President’s own capriciousness. Rebuilding Venezuela is a years-long project, and at times it seems that Trump has already lost interest in it. Cuba will take far longer, and will require a new level of patience for his administration. But if Trump can retain focus on the long haul of rebuilding Venezuela and Cuba, however, he will have done more to advance American leadership in its near-abroad than any president in decades. And conversely, he will not be able to achieve his goal of reasserting the Monroe Doctrine and reestablishing US dominance over the Western Hemisphere with a blood enemy in Cuba.