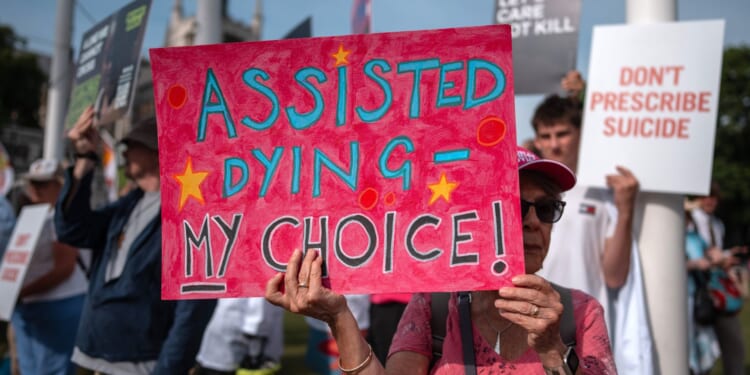

The Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill, which reaches committee stage in the House of Lords this week, is all but certain to make assisted dying legal in the UK under certain strict circumstances. As the Bill has made its slow, faltering progress through Parliament, it has prompted impassioned arguments from proponents, opponents and the terminally undecided alike.

But what all sides agree on, at least officially, is that they are against what we might call Death-on-Demand. This is the kind of scenario caricatured in the TV series Futurama: in the year 3000 there are “Suicide Booths” on every street, operating under the brand Stop’n’Drop. Customers can exit this mortal realm for a mere 25 cents, opting for either “Quick and painless” or “Slow and horrible”. What Futurama satirises, of course, is a hyper-liberal attitude to assisted dying, one where suicide becomes just another consumer choice, no different from walking off the street and buying a sandwich. And nobody wants that. Right?

Well for a couple of years, I did.

If we lived in a world of Death-on-Demand, I would not be here to write these words. In August 2023, I had a rock climbing accident that left me paralysed from the collar bones down. I spent roughly the next two years wanting to finish the job that the mountain had started. In an instant, my life as I knew it was destroyed. Along with my mobility went my sense of identity, purpose, meaning — the lot. In their place I got double incontinence, loss of sexual function, loss of the ability to enjoy exercise, dress myself, feed myself, wash myself; loss of pretty much everything a man in his thirties ordinarily takes for granted.

Instead, I entered a form of living in which merely staying alive meant becoming completely dependent on other people. Typically, those people were low-paid, foreign care workers to whom I had nothing to say — even when they could speak English, which was less often than you’d expect. I went from climbing mountains with friends, to staring at walls by myself. And every day, for two years, I wanted to die.

Maybe not all day, every day. But at least once a day. I just wished that the accident had fucking killed me. Nothing, I thought, could be worth losing everything that I had lost — and certainly not if the price of living meant living like this.

My death urge came awfully close to being more than just thoughts. In the early days, during spinal rehab, I worked out that I could freeze myself to death simply by going out into the garden at night and unplugging the wheelchair. (Trust me, it would have worked.) But the more sensible option seemed to be to join Dignitas. Being unable to access such a service in the UK, I applied for assisted dying in Switzerland.

Dignitas, however, won’t just help anyone to die. Because I was not terminally ill, and my medical records stated that I was suffering from severe depression (which I very much was), Dignitas would not move forward until my application was signed off by a psychiatric professional confirming that I had mental capacity. However, under UK law, no British-based psychiatric professional could legally sign such a letter.

There was another Swiss clinic with less stringent requirements — but they were no longer taking overseas applications after getting in trouble with the Swiss authorities. Assisted dying is legal in Belgium and the Netherlands, too, but they’re much tougher to travel to for these purposes than Switzerland.

So, I decided to go DIY. One night lying in bed, I decided: that’s it, I’m done. I’ve tried, I really have. I’ve given all that I had to give. There will be no note, no final goodbyes. Just a blessed nothingness.

I made it as far as the footbridge by the station. Not to the platform itself, but looking down to the tracks. I watched a train go by. The next one, then. I didn’t want to go out like that — even if only for the sake of the people who would have to deal with the mess I left behind, both literally and metaphorically. But when you’re paralysed from the chest down with only minimal use of your hands, there aren’t many options.

I didn’t do it. Obviously. And I’m happy to report that things did eventually get better for me. I turned a corner. It helped a lot that I had a job to go back to — I’m a lecturer in political theory at King’s College London — as well as a network of family and friends who continued to support me throughout the ordeal.

At this point you’re probably expecting me to say something like: “So thank God I wasn’t able to access assisted dying during my darkest hours, or else I wouldn’t be here now!”

Except, it’s not that simple.

For a start, when I was at my lowest, there was just no guarantee that I would indeed make it out of the darkness. It is not a coincidence that suicide is a leading cause of death for people with spinal cord injuries. Some just never come to terms with it, and choose instead to make the misery stop.

Back then, I was pretty sure I was one of those people — and the truth is, I might still become one again in future. Right now, I’m not gripped by a depressive desire to end it all — but it doesn’t follow that it would have been an obvious mistake if I had shuffled myself off this mortal coil. There remains a real possibility that one day I will recalculate and decide that I do now want to chuck it in. And if I do recalculate in that way, I think it would be good if I could proceed without needing to go abroad and deceiving various domestic agencies about what I was up to. Certainly, without having to throw myself in front of a train, or drown myself in the local canal (my other leading option, though I am terrified of what those final moments might feel like). I would prefer to call it quits in an orderly, legally structured manner, in a hygienic and predesignated location with the assistance of professionals. I would like to be able to say goodbye (or not!) to select people in advance, without having to keep secrets so as to protect loved ones from prosecution. I would like to make as little mess for others to clean up as possible — both literally and metaphorically.

Still, it is important to stress that the proposed change in UK legislation alters nothing for me personally. To be allowed to die under the new Bill, you must be already suffering from a terminal illness; you must have less than six months to live; and you must comply with strict eligibility criteria requiring both medical and judicial oversight. Unless I get diagnosed with a terminal condition leaving me with less than six months to live, I simply won’t be eligible for assisted dying in the UK under the new law.

The situation, of course, is very different for people who are indeed already dying, usually in agonising pain, whilst becoming ever more dependent on others as their body fails them in myriad shame-inducing ways. (Trust me, losing control of your bowels really is shame-inducing, no matter how often well-meaning people tell you that it “shouldn’t” be. It just is. If you don’t believe me, try it.) For these people, there simply is no prospect of their getting better the way that I did. What the change in UK law is offering to them is the option of bringing the inevitable about more quickly, with less pain and less torment. And not just for them, but for their families too.

So while I will be unaffected by the legalisation of assisted dying, if nothing else, my peculiar vantage point has led to me having no patience for some of the more commonly heard arguments against it. The first is a worry that vulnerable people, particularly the elderly, will feel pressured into committing suicide so as “not to be a burden” on remaining family.

Well, yes. For a long time, I wanted to die precisely because I had become a burden on other people. Now to be clear, they all assured me that I wasn’t a burden; that they cared about me; that they didn’t want me to feel like I was any such thing. And I’m sure they meant it. But the facts were plain, or so they seemed to me. Instead of being an independent man in my thirties, forging my own path, I was forcing my parents to once again manage my life. I became, in my mind, little more than a baby — but now faced with the prospect of never growing up. And I couldn’t stand it. Being forced into such dependence was a leading factor in why I wanted it all to stop.

“For a long time, I wanted to die precisely because I had become a burden on other people.”

That I have gradually become somewhat less of a burden is a significant factor in why I decided to keep on going. But for people who have no prospect of things getting better, it is crucial to understand that being so utterly dependent on others really is one of the things they want delivery from — along with all the other horrors.

A second argument is that assisted dying will “cheapen” life. That by making it something people can opt for, it will become akin to a consumer choice, thus undermining the sanctity of life — which we must absolutely not allow to happen. This sometimes gets bundled up with a suspicion about overly permissive liberal attitudes — about how we mistakenly prioritise the supposedly rational autonomy of sovereign individuals over the bonds of community.

But while this is good material for a Futurama caricature, it’s an unrealistic depiction of how actual human beings face their own deaths. Take it from somebody who has gazed hard into the abyss.

Our complex ape brains, hardwired to prioritise survival by millions of years of evolution, do not destroy themselves on a whim. To go through all the rigours of legal and medical oversight required to access state-sanctioned assisted dying, you really have to want to go through with it. There will be nothing cheap, nor cheapening, about people exercising such an option in an appropriately structured institutional framework, as is proposed by the change in UK law. Assisted dying is not a sandwich — and the last people who will need to be reminded of this are those who seek it out.

Where opponents of assisted dying have a stronger case is focusing on how large-scale institutions inevitably get things wrong. The NHS is already underfunded and overstrained. Doctors make mistakes. The frequency of these mistakes is exacerbated by the high-stress situations that have become routine in a struggling healthcare system. Meanwhile, an ageing population means there is even more pressure to free up NHS resources. Is now really the time to ask doctors to make literal life and death decisions? Shouldn’t we be trying to relieve people’s suffering rather than simply eliminating them?

These are important arguments, but on balance I don’t find them convincing. For one thing, doctors already make life and death decisions in hospitals on a daily basis. We would really just be formalising a process that happens anyway, just in a haphazard and delayed manner. But regardless, what defenders of the Bill should properly do is admit that, yes, mistakes will be made.

“What defenders of the Bill should properly do is admit that, yes, mistakes will be made.”

In a vast bureaucracy like the NHS, it is practically inevitable that not everything will work perfectly. There will be tragic cases where it appears the system has failed. There will be heartbreaking stories and we can expect to read all about them in the media. Of course, you won’t read about the hundreds of cases where everything worked as it should — but that’s just how the media works.

However, it is an error here to think that because mistakes will be made, the most appropriate thing to do is maintain the status quo. This trades on the fallacy that the status quo is somehow morally neutral — and that we will be exchanging it for something morally bad if we support assisted dying.

In fact, what we have is a choice between two deeply imperfect scenarios. The first is the one we have now: people in agonising pain, with no prospect of physical recovery, enduring psychological torment in a personal hell which intensifies every day, being told that they must continue until nature takes its course. A world where even the most perfect provision of palliative care would barely soften the edge. A world where we use the power of the state to deny them and their loved ones the option of making the horror stop sooner rather than later.

The second scenario is the one that the Assisted Dying Bill proposes to try and bring about. It will offer relief to the people currently trapped in the scenario above. Its supporters will have to admit that things will go wrong in practice, and that changing the institutional machinery of the NHS will inadvertently harm some future people — how many, we do not yet know. And we will have to acknowledge that this will take place against the backdrop of an ageing population, a crumbling health service, sclerotic public finances, and unforeseen future challenges.

Trying to exchange the first scenario for the second is, in my estimation, a gamble worth taking. But it is a gamble, not some straightforward exchange of the morally bad for the morally good. It is about weighing up which bad outcomes we are going to tolerate in the hope of reducing others; the price we are prepared to pay. It is about how much agony and torment we are honestly going to face up to as a society, publicly acknowledging what is already a fact of life for thousands of people.

With honest reflection and dialogue, we stand a chance of getting things, if not finally right — then a bit better than they presently are.