There aren’t many opportunities left on planet Earth to boldly go where no one has gone before. One might think of the remote wastes of Antarctica, or of dense tracts of Amazonian jungle. But a new frontier has opened — and in a rather unexpected place. Under a sheep-grazed meadow in Gloucestershire’s Forest of Dean lies Britain’s biggest cave discovery in decades.

It is a find that we can credit to one of Britain’s greatest assets: hobbyists. Their work has taken place beside the village of English Bicknor, a little to the east of the picturesque wooded hill that is Symonds Yat Rock. Close to the village is a stream that sinks underground at a point near Redhouse Lane, the road that connects English Bicknor to Symonds Yat. If the locals did but know it, in this heavenly countryside lurked a portal to the underworld.

A local caver, Paul Taylor, knew of the underground stream and was aware of the long-held suspicion among geologists that the Forest of Dean contained undiscovered big caves. As a result, he began to investigate the Redhouse Lane site in 1990. Taylor, now 71, who lives in Gloucester and was working then as an engineer, enlisted some fellow cavers. Aiming to scope out what might lie beneath them, one of them poured dye into the vanishing stream. Some time later, tinted water was detected emerging some 2.5 kilometres away, at a large resurgence — cavers’ term for a spring — on the banks of the River Wye.

What lay between the sinking stream and the resurgence was anyone’s guess. But it was well-watered, of considerable length, and untouched — all tantalising qualities to subterranean explorers. In his book Limits of the Known, the American adventurer David Roberts, a pioneer of difficult climbs on remote, Arctic peaks, reflected on the impulse that, for many centuries, has driven some of us to extend our knowledge of our planet. “Why have I spent my life trying to find the lost, unknown places of the world?” he asked, “and what have been the passions of explorers across human history?”

He reached two conclusions: first, that driving every explorer was a consuming obsession, a thirst to be first that meant the allure of unseen territory trumped the risk and cost of finding it. Indeed, caving often gets you cold, muddy and wet, and can — as in Redhouse Lane — involve forcing yourself through openings barely big enough to admit an adult human being, driven by the hope that around the next bend, there will be a huge, majestic borehole. Secondly, Roberts wrote that with the whole of the planet’s surface mapped and visible from orbital satellites, if he were to try to find unknown territory now, “I might become a caver, rather than a climber… for if ever an era of geographical exploration deserved to be called a golden age, for cavers that time is now.”

He was right. The Redhouse Lane site, back in 1990, was a case in point. All that was known was that the watercourse was swallowed by the earth and spat out elsewhere. There was no way, at that point in time, of getting to see what might lie in between. Taylor and his hobbyist friends, from the Gloucester Speleological Society and the Royal Forest of Dean Caving Club, would have to make a route of their own. They would have to dig to remove the vast quantities of boulders, stones and hard-packed mud that blocked the possible route.

The digging team usually worked every weekend and on a weekday evening, sometimes until late at night. After months of effort, they had removed tonnes of spoil from what is now the cave’s vertical entrance shaft, and reached a mostly constricted horizontal cave through which flowed the stream. Soon they came to a “duck”, a narrow passage mostly filled with water. They pumped it out to create a few centimetres of airspace — the first of several such obstacles. Further in was a longer, almost-flooded tunnel, and to pass it they called for assistance from Martyn Farr, a famous Welsh cave diver who has found new caves across the globe. They sent Farr into the darkness wearing scuba gear, hoping for good news.

Eventually, Farr returned. He had passed through a low, winding tunnel tens of metres long that was almost filled with inrushing water. It had been a tricky journey, but not an impossible one, and not one that required scuba gear. Thus reassured, the hobbyists followed him back in.

Eventually, after almost 200 separate trips, they got to the apparent end of Redhouse Lane in 1992: an impenetrable pile of boulders. As cavers always do, they had made an accurate survey as they advanced. With side passages added in, the system’s total length was 1.4 kilometres: a respectable discovery, but not exactly caverns measureless to man. Redhouse had a reputation as an arduous adventure with at best a modest reward, and no one entered it for years at a time. There was just one sign to indicate there might be something much bigger on the far side of the boulder fall: in places, the “original” cave carries a strong, bone-chilling draught.

Enter, in the early summer of 2023, Tim Nichols, the organising force behind Redhouse Lane 2.0. A now-retired physicist and engineer aged 60 who lives near Cirencester, he had been an active caver in his youth, but raising a family had got in the way of exploration. A caving geologist told him he was convinced there was “a lot of untapped potential”, and on the strength of that, Nichols asked Taylor to show him round. Suitably impressed, soon he had put together a core digging team of five.

“We used to go in on a Wednesday night, get to the end in about 40 minutes, dig away, and then go back out again,” Nichols told me. They had to use drills to get past some of the fallen rocks, and in places it was “really desperate — flat-out around boulders, with hanging death lurking above”. On 10 August 2024 they broke through. That first day, there were only two of them present. “We stood up in this enormous passage,” said Nichols, “and it was like the Wizard of Oz, when Dorothy gets whisked away and says, ‘I’m not in Kansas anymore’. We felt we weren’t in Redhouse Lane — but we were.”

On the next trip down that first trunk passage, picking their way through the blackness across the wobbly boulders that littered the floor, they stopped at a chamber now known as Tiff’s Treat, in honour of digging team member Tiff Cooksley-Czajka. There was much more to come. By the time the autumn rains rendered the crawls impassable, they had already explored several major branches and given them evocative names — “We’re Off to See the Wizard”; “Cryogenic Causeway”; and the “Marble River”, which was a tunnel heading straight for another local cave system blessed with a crystal floor. Taylor was able to join them: “When I saw what there was, what we might have found years earlier, I felt choked”.

Keen to resume exploration, the group made their first forays into the cave in early 2025, when water levels were still high. But since late March, near-drought conditions have rendered the cave safer and more straightforward. And so to the May bank holiday, when along with cave photographer Bartek Biela, Nichols arranged a visit for UnHerd.

We each carried rugged “tackle bags” containing two litres of water and plenty of high-calorie food. We wore one-piece fleece undersuits, nylon coveralls, helmets and waterproof gloves, and used headlamps powered by lithium-ion batteries and LEDs that would need to last for many hours. Experienced and well-prepared as we were, we were all aware that rescuing someone on a stretcher through the wet and sinuous crawls near the entrance would be impossible. Caving is not as dangerous as high-altitude mountaineering, but it is not without risk, especially in a newly-discovered system where there is a lot of unstable rock. An accident in Redhouse Lane — something as seemingly trivial as breaking a leg by slipping from a boulder — would be a serious event. The only way to get an immobile casualty out would be to use drills and explosives to widen some of those crawls, which would take days. In Redhouse, flooding is also a risk, and having once lost a friend caught by flooding in a cave in France, I was glad the forecast was for dry, settled weather.

I’d already been to the cave once, for a look at the tunnels branching off from the underground junction beyond Tiff’s Treat known as Mindless Optimism. This time, we were heading north, into passages first explored barely a month ago, that head towards the Wye.

Near the entrance we had to negotiate the narrow, horizontal slit. Its dimensions were akin to a long coffin, and it was to be navigated on one’s back in the flowing stream: wriggling and grunting with my ears in the water, my chest compressed against the ceiling, I made it through. Beyond was a lot more crawling. But beyond the 2024 breakthrough, much of the cave was enormous, a dark infinity that swallowed up our lights.

“A dark infinity swallowed up our lights.”

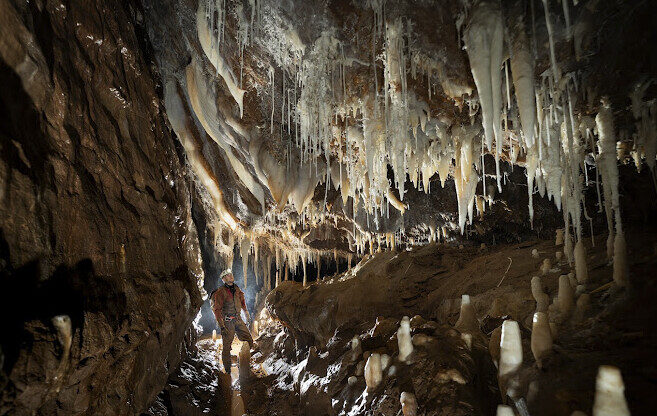

We tackled two exposed freeclimbs, on which we need ropes, and a 20-metre vertical shaft — the Wicked Pitch of the North — down which we abseiled. (To get up again, we would need to use a system of moveable clamps that grip the rope.) Finally, the size of the tunnel we were following began to diminish, and we entered a box of underground jewels. This was the White Forest.

Making progress in this part of the cave requires immense care, for on almost every surface, walls, floor and roof, gleaming white formations sprout, some of them very fragile. To stumble here would be to smash natural marvels that have been growing in the silent darkness for many thousands of years. Some think the cave was formed before the Wye adopted its present course, which means that to despoil it now would be an outrage. There are great crystalline banks and stalactites and stalagmites adorned with tangled, calcite filigrees — what cavers call helictites — as if made of Venetian glass. Sated, after taking photographs we headed for the entrance, aware that reaching it would take at least five hours: The White Forest is not only beautiful, but remote. In all, we were underground for nearly 12 hours.

As I write, ten days after our visit, the cave survey being compiled by Tim has grown again via still more fresh discoveries, including a significant extension to the passage followed by the stream. The total length of Redhouse Lane now looks certain to exceed ten kilometres, and if the explorers make the connection to the nearby Slaughter Stream Cave, this will take their combined length to more than 24 kilometres. It’s also likely that another entrance can be found near the end of the White Forest, although opening it will probably require excavation.

Other possibilities for undiscovered country lie elsewhere in the Forest of Dean: huge resurgences where major watercourses burst into daylight from the unseen depths. The thrill of revealing them makes wet ears and sore knees an acceptable price. Cavers grow tired of being asked by non-adherents why we do it. Redhouse Lane Swallet provides an answer.