On Saturday afternoon, a strange assembly of Christians gathered outside Downing Street. There was Ceirion Dewar, a renegade Anglican bishop with a booming Welsh brogue. There was Rikki Doolan, a follower of Uebert Angel, a Zimbabwean prophet who speaks in tongues and cures cancer. Evangelisers from a staggering variety of churches walked among the crowd, pressing homespun leaflets into cold palms. Believers chanted “Christ is king” and “Tommy, Tommy, Tommy Robinson” and sang along to Mariah Carey’s All I Want for Christmas Is You.

Some were wearing Christmas hats and one woman was selling them, though many were also convinced that the festival’s spirituality had been downplayed in favour of secular commercialisation. To get to this gathering, attendees had walked down Whitehall from Trafalgar Square, which is currently displaying an elegant wooden nativity scene, a giant menorah and a sculpture on the Fourth Plinth featuring the faces of hundreds of trans and non-binary people, which seemed a fitting reflection of our confused public realm.

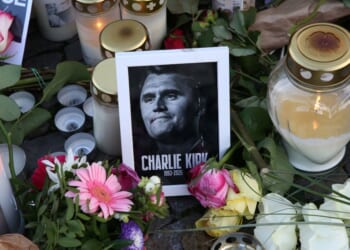

They had come at the invitation of Robinson to sing carols and, they said, to put the Christ back in Christmas. In September, I had watched tens of thousands march down the same street for a protest organised by the former EDL leader in which Christianity took a surprisingly prominent role. Demonstrators brandished giant wooden crosses and framed photos of Charlie Kirk, who had been shot just days before.

By contrast, the carol service was to be a more intimate affair, with around 1,000 in attendance. The crowd was genuinely diverse, with many fervently devout Africans trying to recruit to their own churches and noticeably fewer young white men than at a typical Robinson march.

Like Robinson, many of those at the service had little time for the Church of England. Steve Edwards, sitting in a collapsible chair as he ate a chicken bake, said he found the Church of England disgusting. “It’s full of wokeism,” he told me, a Union flag flying above him. “I went to church as a kid but it was not my choice. I don’t go now.” The advertisements about the carol service had been clear that it was not a political event: it was solely about celebrating Christ and Christmas. For Edwards, however, there was clearly a political resonance to such an act. “I think my prime motive for coming is to defend Christmas against the Muslim hordes and eroding of our culture,” he said. “It’s a day out, but a useful day out.”

To the left of the stage stood a group of women wearing pink who had been campaigning in Havering against the housing of asylum seekers. Kim, a founder of the group, said that, although she was a Catholic, she did not consider that to be related to her activism. She was also not opposed to people practising other religions, she insisted. “They can have theirs and we can have ours,” she said. “The key word is love: everybody should love each other.” There were limits to that love, however: the women were clear that they did not wish to have undocumented and uninvited small boat migrants in their town.

Soon enough, the service began. Instead of a pulpit, there was a temporary stage on a trailer flanked by large, white crosses and garlanded with tinsel. Preachers reading extracts from the Bible alternated with musicians, including Doolan’s band and Star, a young black woman with a mellifluous voice. The crowd sung along to the hits — from “Come All Ye Faithful” to “Away in a Manger” — and speakers exhorted us to pray for persecuted Christians in Nigeria and Pakistan.

Several of the speeches drifted from theology to politics. Liam Tuffs, a long-term Robinson wingman, declared that he had not been a Christian himself but that he planned on pumping religious content out from his social media channels in 2026. “Young Bob”, a 17-year-old activist with a mop of hair, spoke of how he had become depressed and suicidal at secondary school as he committed the sin of atheism and other “sinful acts”. If it were not for Jesus Christ, he said, he would not be here. If it were not for Jesus Christ this nation would not be great. “And wouldn’t it be great to see this nation restored back to its ancestral roots?” he asked to cheers.

Walking among the crowd was Robert Wallace, who claimed, when we spoke, that had been to prison in five countries. He said had swallowed balloons of drugs to smuggle them. He spoke of how he had sunk into alcoholism and casual violence and lost himself for a time to a kind of madness that took over his life. But now he has rediscovered Christ and been born again. And so, he and his brother, John — both short men with greying hair buzzed low — found themselves at the carol concert.

Born 18 months apart, the pair look as if they could be identical twins. “When we were younger we went to Sunday school and church,” said John. “A lot of people lost that root. Now they’re turning back.” For the brothers, Christianity represents their childhood and a lost Britain of innocence and moral rigidity. “We used to run around outside and pray,” Robert said. “Then, when I came out of the army, we [Britain] were in Europe. Our country is flooded. It’s changed.”

With their lives of sin and winding journey to Christ, the pair were not so dissimilar to the man who had brought them to central London. Though raised by an Irish Catholic mother, Robinson has said he was not religious himself growing up. When dark had fallen and the carols were over, he finally took the stage. The crowd pushed forward a little and began chanting his name, as if forgetting for a moment that this was a religious festival and not a rally.

Robinson spoke of his hatred for Britain’s Anglican establishment. “When I started [the English Defence League] in 2009, the Church stood against us in every city we went into,” he said. “The Church leaders stood and opposed us. That drove me away from Christianity. In fact, I hated the Church for them betrayals. We, all of us, were their lost sheep. The way they’ve acted this week [by criticising Robinson as divisive] is the reason churches are empty.”

It was only during a recent stint in HMP Woodhill that he began speaking with a chaplain and studying the life of Jesus. Then, he was visited by Doolan, a former musician who — by his own telling — spent his life partying and sinking “endless cocktails of drugs” before he stumbled across a Sunday service and, struck by its beauty, was driven to repent. Thirteen years later, Doolan is a pastor at Spirit Embassy, a Pentecostal church led by a charismatic Zimbabwean prophet. His band is a regular feature of Robinson’s rallies.

Speaking to me a few days before the carol service, Doolan said that he had sat with Robinson inside prison and talked for two hours about the Gospel, a spiritual awakening he believes is taking place in Britain, and the importance of Christianity to our national history. “He said that he’d always felt a presence when he was going through, you know, hard times or heavy persecution or whatever it is that he’d been going through,” he said. “There would always be a feeling of something willing him to continue.”

With two prison guards standing over them, Doolan led Robinson through a prayer of salvation. The former English Defence League leader, a veteran of a Luton hooligan firm, convicted of assault and fraud, who once bragged on camera that he could score gear anywhere in the world, admitted his sins and asked Jesus to enter his heart.

“Standing amid the tinsel and the crosses, Robinson proclaimed that ‘something great’ is happening in Britain”

The carol service, which Doolan was heavily involved in organising, was aimed in part at helping others follow Robinson’s path. Standing amid the tinsel and the crosses, the activist proclaimed that “something great” is happening in Britain. “I’ve seen it at each one of our Unite the Kingdom events as I saw the cross start playing prevalence, as I saw ‘Jesus is king’ [banners], and I felt something happening and I felt it again today,” he told the crowd.

Not every Christian in attendance was willing to take this change of heart at face value, however. As I watched a series of Bible readings on stage, I was approached by two young men, one German and one English, from a non-denominational church in London. “Tommy is not really a Christian,” said the German. “He doesn’t follow the Bible.” While he could not know the contents of Robinson’s heart, he said, he did not believe he had truly renounced sin.

The duo were at the protest to evangelise to those who believed in God but were not yet practising Christians. The faith, the Englishmen said, had saved his life. With the Union Flag pulled over his shoulders, he launched into a denunciation of the nation’s spiritual values. All men in this country care about, he said, is chasing women and going to the pub and doing bumps of coke. If he had not found Christ, he would still be doing the same, he added.

The vicar of Holy Trinity Church in Tooting, who coincidentally is called Angela Rayner, was handing out leaflets with an AI image of the nativity featuring black people, Muslim women and three white men wearing Union Jack T-shirts gazing at baby Jesus in his crib. Only one in 10 people at most would take a Christian flyer outside a train station, she told me. Here, almost everyone was willing to accept them. She hoped she might be able to convince fans of Robinson that everyone was welcome in the Church of England.

Earlier that day, another group of Christians had gathered outside St Paul’s Cathedral to counter Robinson’s message. I watched as they staged a nativity scene in which two people playing Joseph and Mary sat in a small rubber dinghy. Behind them, about a dozen others in smart coats, woolly jumpers and hiking boots were singing hymns and holding banners that claimed Jesus as a refugee. “Love your neighbour,” read one, in red letters, with another below adding, in black spraypaint, “that includes the ones in hotels”.

Walking about in front of this display was Krish Kandiah, an evangelical leader and founder of The Sanctuary Foundation, a charity that supports refugees into work and housing. He is, I suggested to him, exactly the kind of Christian Robinson professes to revile. The former EDL leader had only recently become religious, though, Kandiah said. Robinson had clearly not yet developed a real understanding of Christianity.

“We need to help Tommy get to the heart of the faith,” he said. “The Bible is very clear that every human being had intrinsic value and worth.” While Kandiah accepts that some people fear immigration is out of control, he also believes that Britain has the capacity to help those in need. “We need to work out our responsibilities to them,” he said.

Kandiah said he was concerned that people were using the Christian message to gain followers for cynical reasons. “It is hard to understand how Christians of good faith can hate on people and promote division,” he said. The scale of the messaging operation coordinated over the past week by the Church of England and other mainstream Christian groups implies they are deeply concerned that Robinson’s position might catch on.

The feeling of resentment and suspicion is mutual. When Dame Sarah Mullally was named as the next Archbishop of Canterbury, Robinson retweeted a statement she had made backing the Black Lives Matter movement and wrote: “their churches will stay empty, a Christian revival will grow on the streets. Masculine christiany is coming not this weak drivel.”

The idea that Christianity is experiencing a revival in Britain is one shared by many worshippers who both love and hate Robinson. A report published by the Bible Society earlier this year claimed that church attendance had surged since 2018, driven in particular by young men. “People are giving church a try, or something has drawn them back in again,” the Evangelisation coordinator for the Diocese of Westminster, Teresa Carvalho, told The Guardian. Others have questioned the value of the society’s evidence, however. David Voas, an emeritus professor of social science at UCL, has pointed out that its report was based on unreliable opt-in surveys rather than probability sampling. The Church of England and the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales record shrinking turnouts since the pandemic.

When I spoke to Doolan, the musician-turned-pastor, he said he had witnessed growing Christian faith. This was evidence, he argued, that I could expect to witness, in my lifetime, the arrival of the Antichrist, who will take control of a one-world government. The “masculine Christianity” advanced on Saturday, under which the Church’s move towards liberalism on borders, gender and sexuality would be reversed, may therefore be one element of a Christian revival, even its driving force.

After Robinson spoke on Whitehall, there was time for one last carol. Attendees held plastic candles with electric lights aloft and began to sing “Silent Night” amid a reverent quiet. For those in attendance, though vastly smaller in number than previous Unite the Kingdom rallies, this was the start of an epochal shift. Next year, Robinson said, he would host the same event again and, he claimed, he would pack out Trafalgar Square. Then the Church of England would really have something to worry about.