The pointlessness of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) has been highlighted once again by the United States’ attempt to take Greenland from NATO ally Denmark. This reflects the deepening conflict between NATO’s main sponsor, the US, and its main beneficiaries in Europe.

As it stands, the US is effectively shifting its foreign-policy focus away from Europe, and towards the Western hemisphere. This was certainly the message of the Department of War’s National Defence Strategy, published last week, which followed the White House’s National Security Strategy, published in November. These state that although the US ‘will remain engaged in Europe’, America ‘must – and will – prioritise defending the US homeland and deterring China’.

To show that it means business, the US informed its European allies last week that it intends to withdraw around 200 American personnel from NATO’s institutional structures. According to reports, there has been a ‘silent US drawdown of officers from the alliance’. After a visit to NATO headquarters in Brussels last month, one British officer said that there were almost no Americans there – with the exception of ‘a very low-level token presence’.

The US’s withdrawal poses an existential threat to the future of NATO. Without the full support of Washington, NATO will no longer be able to guarantee the security of its member states. The US is effectively removing its European allies’ security blanket. As an analysis in the New York Times concluded, ‘NATO as we know it, the alliance that has been the bedrock of transatlantic security for over 75 years, is coming to an end’.

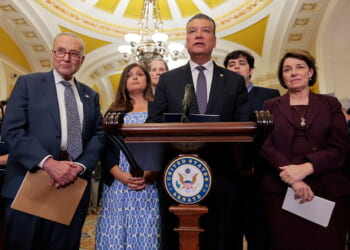

In response, Europe’s panicking political leaders are now frantically attempting to revive it. Last week, we saw NATO secretary general Mark Rutte, alongside Danish prime minister Mette Frederiksen, desperately trying to show how important NATO still is. As Rutte put it on X: ‘We’re working together to ensure that the whole of NATO is safe and secure and will build on our cooperation to enhance deterrence and defence in the Arctic.’ Frederiksen agreed, stating that ‘defence and security in the Arctic are matters for the entire alliance’.

But in reality, NATO has become a Potemkin alliance. It lacks the will and leadership to take the initiative in Greenland, let alone the broader Arctic. After reports last week that NATO allies were prepared to engage in an Arctic mission, US general Alexus Grynkewich said that NATO hadn’t started planning one as there had been no political guidance to do so. As usual, without the approval of Washington, NATO remains in a state of paralysis.

Of course, NATO has faced challenges to its cohesiveness before. The Suez Crisis in 1956 led to a temporary intra-alliance rupture, with Britain and France going to war with Egypt without consulting other NATO members. The US subsequently forced Britain and France to abandon their plans to depose the Egyptian president and regain control of the Suez Canal. This was a clear indication that America held sway over its NATO allies.

Aggrieved at its subordinate status, France left NATO’s integrated military command in 1966, before eventually rejoining in 2009. In the 1974 Cyprus Crisis, two NATO members – Greece and Turkey – went into battle against each other, with Greece withdrawing from NATO’s military structure for years, while remaining a formal member.

Throughout much of the post-Second World War period, NATO and the Western alliance more broadly were effectively sustained by the Cold War. US-led Western powers’ opposition to the deeply flawed Soviet Union provided them with cohesion and even a sense of moral superiority. But once the Soviet Union disintegrated and the Cold War ended, Western powers became increasingly morally and politically disoriented.

In the years since, NATO has increasingly faced existential questions. And no wonder, given it has lacked a unifying purpose in the absence of its old Cold War adversary. At the same time, the US has appeared increasingly resentful about the significant military and financial commitment it had to make to support the security of its alliance partners. That NATO had lost its way was exposed by French president Emmanuel Macron in November 2019 when, in an interview with The Economist, he described NATO as ‘braindead’.

During the years following Macron’s outburst, NATO has remained in a state of institutional paralysis. Doubts over its purpose and relevance were temporarily assuaged by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. This allowed Joe Biden’s US and its European allies to present a united, cohesive front.

But there was always a lack of substance to the posturing of NATO members. Their support for Ukraine was constrained by their fear of provoking a direct conflict with Russia. And despite their constant pledges of support, they rarely seemed willing or able to provide Ukraine with the resources it has asked for to defend itself. After four years of bitter conflict, the impotence of Europe’s NATO members has become all too clear. In a speech at Davos last week, Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, laid into European leaders for always waiting for direction from Donald Trump. He added: ‘Europe loves to discuss the future but avoids taking action today, action that defines what kind of future we will have.’

If NATO was braindead in 2019, today it is thoroughly zombified. Outwardly, it resembles the NATO of old but internally it lacks the meaning and purpose associated with a functioning military alliance.

America’s withdrawal from NATO confronts Europe with a profound question: can it pick up the pieces and construct an institution capable of defending its members? It seems unlikely. European leaders often talk of ‘strategic autonomy’ and taking charge of the defence of their own nations. But they lack the resources and the will to forge a credible alternative to the security system underwritten by Washington. As a commentator in the New York Times notes, even the US’s biggest allies, Britain, France and Germany, cannot truly afford to go their own way:

‘They simply have no replacement for a system where the US stands at the centre of their defensive strategy, bolstered by the American nuclear arsenal… It would take decades, and hundreds of billions of dollars, to replicate what the Pentagon has built up over generations. Few countries in Europe have the stomach for that.’

Little wonder, then, that NATO’s European members have decided that even a ‘braindead’ NATO is preferable to facing a world without the US’s security blanket. But this is not a viable strategy in the long run. The world in which NATO made some sense has gone. European nations need to grow up and confront the fact that they alone must take responsibility for the defence of their interests.

Frank Furedi is the executive director of the think-tank, MCC-Brussels.