Should record income from import taxes be used to pay down the national debt or hand out $2,000 tariff rebates? Should the Supreme Court uphold President Donald Trump’s sweeping global tariffs, the White House will wrestle with this question heading into 2026. The reality, at least based on the available fiscal data, is that neither policy will come to fruition unless policymakers use some Federal Reserve voodoo magic.

Tariff Rebates or Pay Down the Debt

Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, speaking with Fox Business on Nov. 24, said that tariffs are the cornerstone of President Trump’s economic agenda. Despite public disapproval of the administration’s trade policies, according to Liberty Nation’s Public Square average polling data, Lutnick believes sentiment can shift if they are given checks.

“The president wants them to understand how great tariffs are for them,” he said. “And so one of the ways to prove to the American people how great tariffs are is to have them share in a part of one year’s income from these tariffs, and that’s $2,000 a head, as he said, for people who need the money.”

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has suggested that tariff revenue could be used to reduce the national debt, which is currently around $38 trillion. “I think that we’re going to bring down the deficit-to-GDP, we will start paying down debt, and then at a point that can be used as an offset for the American people,” Bessent told CNBC in August.

But President Trump thinks he can do both: trim the national debt and send tariff rebates.

Assuming the high court sides with the administration, the numbers show that it would be difficult to do either: not enough income to make a dent in the debt, and not enough revenue to place stimulus checks in household mailboxes.

Crunching the Numbers

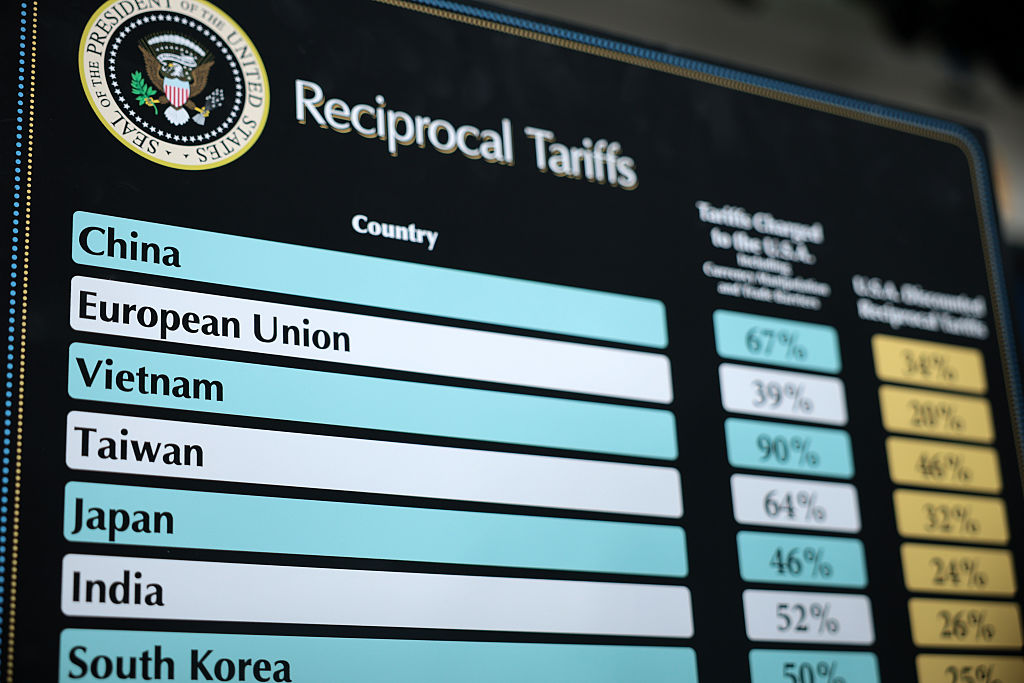

In fiscal year 2025 – Oct. 1 to Sept. 30 – the US government collected $195 billion in customs duties, according to the Treasury Department. Fiscal year to date, Washington has garnered approximately $40.4 billion in tariff revenues. Looking ahead, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimates the levies will generate as much as $90 billion a year, depending on trade flows and enforcement. The Tax Foundation is a bit more generous, forecasting total annual tariff revenues at more than $158 billion.

So, would these funds be enough to pay for either proposal?

Until the federal government balances the budget, which was nearly $2 trillion last year, it would be impossible to pay down the national debt. Let’s define the terms.

First, the national debt is an accumulation of past years’ deficits, and a budget deficit is when the government spends more than it collects. Second, if Washington is in the red, it has to borrow to make up the shortfall, which means tariff revenues are already being absorbed to cover all the spending. Finally, interest charges already eat about one-quarter of all federal income tax revenue.

At this point, it is unlikely the administration will have a balanced budget anytime soon.

The proposed $2,000 tariff dividend remains difficult to assess without details. However, economists at the Tax Foundation have added the dollars, subtracted the cents, and carried the one to determine its feasibility. They concluded that approving tariff rebates for low- and middle-income households would cost between $279.8 billion and $606.8 billion.

“All tariff dividend designs would cost more than the revenue that the president’s new tariffs will generate in 2025, and many designs would use all the revenue they will generate in 2026 too,” the economists wrote in a Nov. 18 report. “In other words, sending out ‘tariff dividends’ in 2026 would leave no revenue to offset the cost of tax cuts or reduce the deficit in the near term.”

Even if stimulus checks are distributed, past data show they have been inflationary. While they do not immediately lead to bouts of price inflation, they typically take about a year to filter through the system (as seen from the two rounds of the Bush rebates in 2001 and 2008 and the post-pandemic stimulus).

In a February 2023 paper, New York Federal Reserve economists concluded that fiscal policy from December 2019 to June 2022 accounted for about half of the total aggregate demand-driven inflation. “Since all good and factor prices are flexible upwards, an increase in aggregate demand maps one-to-one to increases in good prices, ultimately resulting in inflation,” they wrote. Put simply, additional demand pushes up product prices across the board.

This might be why Bessent encouraged Americans to save these checks rather than spend them. “Maybe we could persuade Americans to save that,” Bessent, pointing to the Trump accounts, told Fox News last week.

Wealth Redistribution

Tariffs, no matter how you spin it, are paid by US importers. Yes, foreign exporters can bear some of the cost by lowering their prices to maintain market competitiveness, but US firms will write a check to the Treasury paying the tax. As a result, if the administration’s two schemes are implemented, American taxpayers will be forced to pay down the national debt or give money to each other.