I have a piece at the Wall Street Journal with the title, “Medicare and Medicaid Fail a Basic Scientific Test.” It explores the implications of the fact that Medicaid failed the test the federal government uses to determine whether new elixirs save lives. Basically, “If Medicaid were a drug, the federal government wouldn’t approve it—and could penalize its salesmen with prison time for claiming it saves lives.”

The piece grew out of my bewilderment at the criticisms of a letter to the editor of the Wall Street Journal that I coauthored with Brian Blase on that topic. At the same time, critics of our letter misread, misrepresented, and ultimately failed to engage our argument; they ignored our call for further randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) to reduce the surrounding uncertainty and disagreement.

According to economists Angela Wyse and Bruce Meyer, Blase and I,

- “misrepresent[] the evidence”;

- “focus narrowly on the Oregon [Health Insurance Experiment’s] mortality result”;

- “argue that the Oregon [study] showed that Medicaid does not reduce mortality”; and

- “contradict [their] study’s finding of fewer deaths in states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA.”

Not one of these representations of our argument is accurate.

Rather than contradict Wyse and Meyer’s findings, we write, “We hope they’re right.” Rather than focus narrowly on mortality, we write that the Oregon study “found no improvements in mortality or any other physical health outcome,” including outcomes “amenable to medical care within the study’s timeframe.” Rather than argue that the Oregon study showed no improvements, we write that it found no improvements. (Big difference.) Rather than contradict their finding, which would require more certainty than we possess, we “acknowledg[e] the uncertainty surrounding this question” and “call for the only type of research that can dispel it: further, larger, and longer RCTs of the effects of Medicaid on health outcomes.” You know, like Ezra Klein and others have.

Journalist Jonathan Cohn likewise offered criticisms. Cohn is a great and honest journalist. He acknowledges the “serious debate” about whether and how Medicaid impacts health, where “the link between insurance and mortality is inherently difficult to measure.”

Cohn nevertheless posted Wyse and Meyer’s criticisms despite obvious errors. He quotes another economist who says, “If you were anchoring your policy off of Oregon, you wouldn’t have thought mortality changes would occur.” On the contrary, Oregon suggests not that mortality changes wouldn’t occur, but that we don’t know and should be circumspect about such claims. Cohn writes that Blase and I “said that observational studies were more prone to ideological or political bias.” Not quite. Ideological and political biases are features of humans, not study designs. We wrote that observational studies are “susceptible to spurious results and cherry-picking,” which is different.

Finally, economist Amy Finkelstein is something of a hero to me. This is in no small measure because she was one of the lead investigators on the Oregon study. Finkelstein likewise claims we “misinterpreted” the Oregon study by “misinterpreting the lack of evidence of impacts as evidence of no impact.” Again, that’s just incorrect and not what we wrote. We interpret the lack of evidence to mean we don’t know.

Even more baffling is that our critics are misrepresenting our argument when there are valid counterarguments available. In other work, Blase and I each rely on non-RCT studies to argue that Medicaid crowds out private health insurance and discourages work effort. Yet as Finkelstein and her coauthors write, the Oregon study found that “Medicaid had no economically or statistically significant impact on employment and earnings or on private health insurance coverage.” Did you catch that? It means Blase and I are in the same position regarding our claims about crowd-out and employment effects that Medicaid supporters are regarding their claims about physical health effects. A better line of attack would be to accuse us of hypocrisy. Here we are criticizing others for relying on non-RCT evidence when an RCT failed to reject the null hypothesis of zero effect, while we’re doing the same thing. This line of attack would still be wrong because Blase and I acknowledge the uncertainty in all these cases, apply the same rules to our claims as our critics, and, most importantly, call for “further, larger, and longer RCTs” to dispel these uncertainties (see below). But at least calling us hypocrites would have a basis in reality.

More baffling than the misrepresentations and opportunity costs is that our critics ignored our call for more RCTs. I don’t know why. I mean, let’s resolve the dispute! Better evidence, amirite? Science! Career opportunities! You guys. I’d even let Finkelstein, Wyse, and Meyer be lead investigators and give Cohn an exclusive on the results.

Which brings me back to the purpose of my commentary, which is to highlight an apparent discontinuity in how people react to different types of null RCT results.

As columnist Jennifer Rubin commented on the Oregon study in 2013, “If there had been a giant trial of a heart medication with lousy (i.e., null) results, we wouldn’t proceed in mass-marketing the drug; we might even take it off the shelves.” By contrast, the Oregon study’s null results do not appear to have shaken any priors. Not even a little. Not even enough for Cohn, Finkelstein, Meyer, or Wyse to echo our call for more RCTs. And they’re not alone: health economists generally do not join the call for serious RCTs examining Medicaid or Medicare. Not even amid the growing number of RCTs finding that subsidies produce little to no health improvements.

The most popular heart medications top out at a few billion dollars in spending and 33 million consumers. Medicaid is a product that spends nearly $1 trillion per year and affects 340,000,000 subjects, many of them negatively. Yet most scholars responded to Oregon’s null results by doubling down on their support of Medicaid. I’m telling you, it’s not just striking, it’s weird.

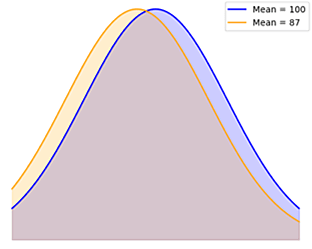

One potential explanation is that we all tend to apply less scrutiny (and assign greater weight) to evidence that tends to advance our preferences, and vice versa. Cohn and Finkelstein consider Medicaid a legitimate use of government power; I don’t know Wyse or Meyer, but I’d bet a nickel that they do too. Because I do not, I naturally demand more and more rigorous evidence before I accept a premise that would tend to frustrate my policy preferences. Would it be fair to say that I’m being obstinate for ideological reasons? Only if you recognize that the other side of that coin is that those who say we should accept less rigorous science are also doing so for ideological reasons (read: they prefer a lower bar for government intervention).

Medicaid supporters might want to heed the timely advice that journalist Matthew Herper offers to drug manufacturers:

If a company is lucky enough to get a medicine through the FDA based on imperfect data, find ways to use the resulting cash flow to generate even stronger evidence, even if you think efficacy and safety are not in doubt. The point of data isn’t just to convince believers, but to silence doubters.

A complementary and even more intriguing hypothesis is that academics who support Medicaid are more willing to accept less-rigorous evidence because they face a conflict of interest. Finkelstein, Meyer, and Wyse conduct empirical research on the world around them. One might think their professions (and the personal traits that led them to be social scientists) would dispose them to demand a higher standard of evidence than others. (Finkelstein likes RCTs so much, she conducted one on Medicaid and is co-scientific director of a research center that exists to conduct them on similar policies.) One might therefore infer, not unreasonably, that if academics like these are willing to accept non-RCT evidence of Medicaid’s effectiveness, then that indicates this is a case where a higher standard of evidence is not necessary.

On the other hand, academics face a conflict of interest. It stems from the facts that RCTs are expensive and that academics attain professional success by producing research that people take seriously. RCTs are so expensive and rare, academics have a professional interest in public and policymaker acceptance of non-RCTs. Were policymakers and the public to start placing less weight on non-RCTs in favor of RCTs, academics could find it harder to publish, influence policy, and advance professionally. Academics thus have professional incentives to prevent the denigration of less rigorous science, because less rigorous science can serve academics even when it does not serve the public.

None of which means anyone is being dishonest. It just means that, in addition to some academics having ideological incentives to do so, all academics have economic incentives to assign greater weight to non-RCT evidence than the public does.

Or maybe that’s not a factor. I’m open to other solutions to this puzzle.