Jesse Merriam persuasively argues that legal conservatives are no longer committed to maintaining the essential features of the American legal and political order. They are instead obsessed with matters of constitutional interpretation, emphasizing the related doctrines of originalism and textualism. So they consider it something of a victory when progressive justices such as Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson embrace those doctrines, even though it’s perfectly clear they will use them for progressive ends. Indeed, even Justice Neil Gorsuch, an avowed textualist, did so in Bostock v. Clayton County (2020) when he insisted, absurdly and ahistorically, that Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act protects individuals from employment discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. His pretextual textualism is as lawless as anything that has animated judicial supremacists since at least the 1950s.

Furthermore, making originalism and its variants the core of legal “conservatism” is a fool’s errand. It does not give conservatives a positive legal language in which to express, or a legal agenda with which to fight, the substantive evils that non-originalist decisions represent. And this assumes that originalism even provides the tools to overturn such decisions, which is hardly clear.

Finally, the narrow interpretive orientation of legal conservatism gives a tactical advantage to progressives, who abhor a vacuum. To the extent the legal landscape is occasionally shifted by originalism, as in Dobbs v. Jackson (2022), conservative political ground is quickly ceded to the Left.

Merriam insists that law must be reconceived “as a way to sustain the American way of life.” But constitutional originalism by itself will not do this, because it runs into the brick wall of the civil rights regime, whose firm ideological commitments are to diversity and anti-discrimination. Originalism, whether due to methodological limitations, caution, or fear, will not threaten “the constitutional morality of the civil rights era.” Both the spirit and the body are weak. So, in the vast areas that touch on civil rights, originalist jurisprudence is doomed to be self-limiting in its willingness to protect the prerogatives of states and individuals in the face of the civil rights juggernaut.

Likewise, religious liberty jurisprudence is now in the business of carving out narrow exceptions to generally applicable laws. And Establishment Clause jurisprudence maintains the fiction that the First Amendment limits the states as well as the federal government, while simultaneously erecting an extra-constitutional and phantasmagorical wall of separation between church and state.

All of this points to a failure of will, linked to legal conservatism’s inability to see that law must be an expression of the good of the whole rather than a narrow technocratic exercise. The question, for Merriam, is how conservatives ought to develop their own constitutional morality to promote shared moral and civilizational goals.

He argues that much of the answer comes down to the judicial nomination process. The goal is to secure judges who can think about “civilizational stewardship” and how to address “the crises of belonging, fertility, and meaning.” Alas, these are moral-political questions of the first order, and they are unlikely to be solved, or even approached, within the context of judging. In this, I agree with Carson Holloway that Merriam “is probably asking what no legal or political movement can accomplish. Any successful practical undertaking must bear in mind the difference between a laudable ambition, on the one hand, and unrealistic expectations, on the other.”

Originalism, properly speaking, is simply what common-law judges do when interpreting written documents—a fact well known to Americans at least since the time of Blackstone. It did not originate in the 1980s with the birth of the modern legal conservative movement. That movement, and particularly Ed Meese’s Justice Department, made originalism visible once again after it had fallen into desuetude due to decades of progressive propagation of distinctly un-American notions such as “living constitutionalism” and judicial supremacy.

But what judges do in interpreting documents is not identical with, nor can it be transformed into, a political program. Judging and legal strategizing are not the answers to our parlous situation.

In fact, Merriam’s solution suggests he shares some fundamental assumptions with the very legal conservative movement he criticizes. In putting his eggs in the judicial nomination basket, he gives far too much away to our legal culture, and especially to the false god of judicial supremacy. To the extent we have a failure of will, it’s a failure of political will. I agree with Ilan Wurman that political conservatism must do some heavy lifting. But I also think this heavy lifting involves not simply filling the vacuums occasionally created by overturning bad precedent, but by cabining the judiciary itself.

Even Supreme Court justices have come to recognize the constitutional untenability of their position, a fact strikingly illustrated by the dissents in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015). Chief Justice Roberts insisted that “the majority’s decision is an act of will, not legal judgment.” It “omits even a pretense of humility,” as it “orders the transformation of a social institution that has formed the basis of human society for millennia.” He also asserted that the Constitution is clear that such a transformation, if it is to be wrought, must come from the people rather than five lawyers who happen to hold judicial commissions. As he rightly asks, “Just who do we think we are?” Justice Scalia suggestively referred to the majority’s decision as a “judicial Putsch” that robs the people of the most important liberty of all—the right of consent to government.

I have long argued that constitutional resistance to such decisions is entirely appropriate and, furthermore, constitutional. Such resistance requires the measured assertion of the supremacy of the political branches, and ultimately the people, in constitutional interpretation. It also requires a commitment to non-enforcement of patently unconstitutional decisions, just as Lincoln advised in his reaction to Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), the earliest and most ignominious assertion of judicial supremacy in American history.

A Judicial Trojan Horse

Recently, Justice Kagan’s assertion that “we’re all textualists now” was repeated by Justice Gorsuch in his concurrence in Loper Bright vs. Raimondo (2024), which overturned the Chevron deference doctrine. We should recall that this doctrine was initially a “conservative” answer to progressive judicial overreach. It was, in part, a bulwark against ravenous judges who intervened to force agency action that conservative presidents such as Nixon and Reagan did not think was in the best interests of the national public.

Loper’s reassertion of judicial control over agency interpretations of their mandate, however, is far from the unalloyed blessing that many legal conservatives and libertarians apparently think it is. The reason for this is largely related to the fact that we’re not all textualists now, and never will be—though increasing numbers of judges claim to be, albeit for tactical reasons. But there’s another reason too, which is masked by the celebration of Loper in conservative circles.

Administrations are elected every four years precisely to set the general direction and tone for a massive administrative state that is otherwise entirely unaccountable to the sovereign people. The administrative state should not be thought of as the plaything of organized interest groups—including litigant groups—over which the public has no control and very scant knowledge. With Loper, we might simply have jumped out of the frying pan and back into the fire of judicial supremacy over the political branches.

Merriam is quite correct that we are at a fork in the road, and that the legal conservative movement is unlikely to lead us down the right path. But it’s not quite for the reasons he suggests. The central problem is not with the movement itself, at least insofar as it lacks a “common good” legalism. The problem is judicial supremacy.

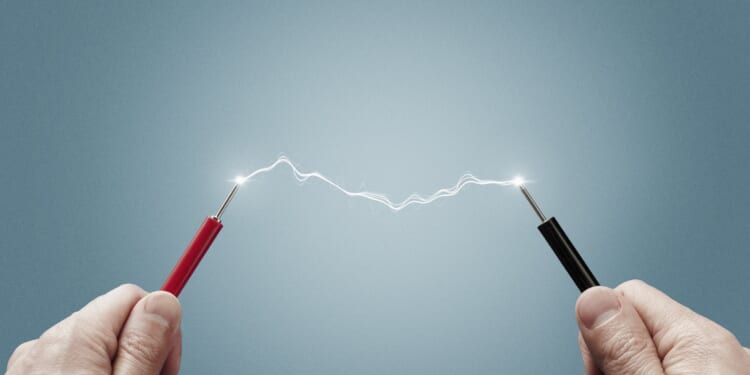

Our lawless legal system needs something much more radical than the reconfiguration of a “movement.” It needs shock therapy. And it is precisely this therapy that the guardians of the conservative legal establishment seem unlikely to countenance. In fact, they are much less likely to countenance it than their contemporary progressive counterparts. And so, after their evanescent celebrations of small victories, legal conservatives will soon enough be back on their heels.