On April 28, 2025, the Spanish population experienced an unprecedented event. The country’s electricity supply was cut off, resulting in a blackout. But to understand what really happened, the context of the situation must be evaluated.

Before the blackout struck, the country was experiencing a seemingly ordinary spring day. Energy demand was stable, skies were clear, and the nation’s increasing reliance on renewable sources like solar and wind appeared to be holding up on levels near historical maximum. However, within seconds, that sense of normalcy collapsed. A massive and sudden drop in electricity generation sent the entire Iberian Peninsula into darkness. Almost 60 million people were left without power, and the event quickly sparked widespread concern, speculation, and a deep examination of the situation. At the critical hours of having lunch and at night people tended to gather in houses where electricity was not needed. (Usually old houses with non-electric tools). This was because people were not ready for a problem like this to happen because they trust and rely on the state to save them.

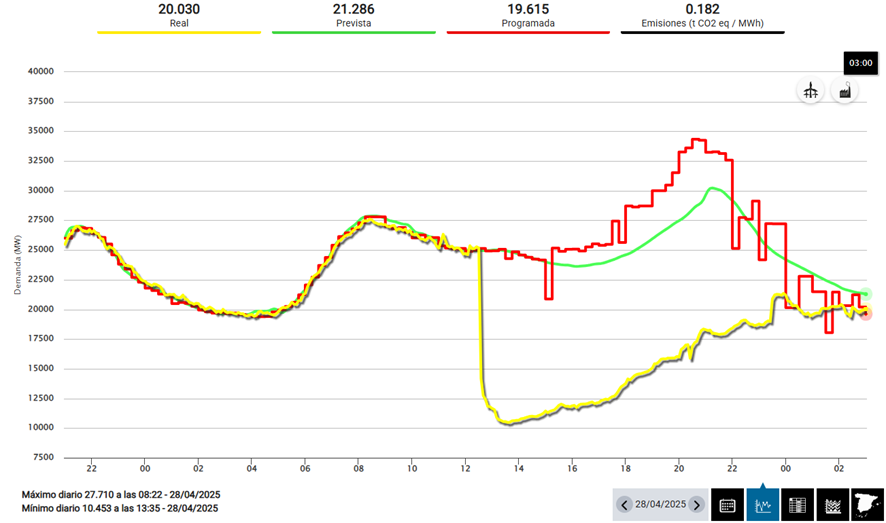

If we look at the chart of the peninsular electricity market provided on the website of Red Eléctrica de España (private company in charge for all the power infrastructure in Spain), we see the following:

Several data series are shown. We should pay particular attention to two of the lines: the red and the yellow series. The red line represents the scheduled energy demand in the Spanish peninsular market, we can treat this as the peninsular demand for electricity to simplify things. The yellow series represents the amount of demand actually being met at each moment. This line should be understood as the electricity supply or the capacity for energy generation that can be fed into the grid.

As we can see in the graph, and as stated by the President of the nation, Pedro Sánchez, at 12:33 PM, the amount of energy supplied suffered a massive drop. According to the statement made by the Prime Minister around midnight: “15 gigawatts of generation suddenly disappeared from the system in just 5 seconds…. To give you an idea, 15 gigawatts are roughly equivalent to 60% of the country’s demand at that moment.” After these remarks, the President informed us that the causes are still under investigation.

In layman’s terms, what happened in Spain was a “short,” the national equivalent of a household circuit breaker tripping. In situations like this, one can always suspect government or corporate conspiracies aimed at influencing public perception. There is also the possibility of an external cyberattack on the Spanish grid, as this system faces numerous daily attacks that are usually neutralized—this time, perhaps one succeeded. However, this last theory is extremely unlikely and, according to Red Eléctrica de España, has already been ruled out due to current security measures. If it was an attack, it would have required an organization as powerful as (or more powerful than) a foreign state, or a sabotage by the intelligence services of other countries. Top suspects could include Israel and the US, due to their demonstrated technical intelligence capabilities. On the other hand, countries like Russia likely had nothing to gain from such a move. Still, an attack is just one of several possibilities.

What most characterized the blackout day was the sun. Solar and wind energies—unlike hydroelectric, nuclear, or combined cycle energy (gas)—are not able to adequately handle changes in the market’s dynamic characteristics like frequency and inertia. This is due to their operation via electronic inverters, while hydro and others use turbines, which are much more stabilizing. The excessive reliance on solar energy introduced fragility into the system, making it easier for an isolated event to bring the whole system down. Other countries like France did not face this risk because of their installed nuclear capacity, prompting a revaluation of Spain’s energy system.

Another possibility we must consider is human error or natural interference. In Italy in 2003, a nationwide blackout similar to Spain’s occurred, and the cause was traced to a fallen tree that damaged one of the lines in Switzerland, where much of the supply came from. This led to overloading and failure of other import lines, causing the system to collapse. Something similar might have happened in Spain, perhaps affecting the supply from one of the major generating stations, triggering the short circuit in question.

The cause will have to be clarified by the investigation teams mobilized in the coming hours or days to solve the issue and prevent a recurrence. But there’s one question we must analyze in this situation: Why did a localized incident in one region trigger a problem across the entire peninsular territory?

The affected areas included peninsular Spain, Portugal (due to its strong electrical connection with Spain), Andorra, and southern France for similar reasons than Portugal. The reason the problem did not spread further than southern France is due to the distinction between the peninsular grid and the French grid—this prevents Paris from depending on what might happen in Seville. If a line in Seville fails for any reason, Paris does not go dark. This is the decentralization of the electrical system. Let’s be more specific: Should a small town in southern Spain depend on what happens in Barcelona?

Currently, the electric system’s answer is yes, because that is exactly what happened during this blackout. But intuition quickly tells us that if a power line between Girona and Lleida fails on the Pyrenees, only the people in those regions should be affected, not those in Seville or Asturias. This is electrical decentralization as a defensive method, this time a structural one. Is it really necessary for the entire Iberian Peninsula’s grid to depend on the entire peninsula at once? Perhaps we should start implementing safeguards to prevent such nationwide chaos. If each village (or group of them) had a grid independent from the issues in other areas, what happened yesterday would not have happened, because taking down dozens, hundreds, or maybe thousands of networks at once would be impossible. We should remember that this already happens in Spain, Baleares, and the Canary Islands operate independently.

This does not mean the grids should not be interconnected. Spain and France are electrically connected and supply each other with energy when needed. What we need is for electrical decentralization to guide our defense and organizational strategy. There is no apparent reason for Spain to operate like a single large household where, when the breakers trip, the whole place goes dark. We should function like a village, where if one neighbor unfortunately loses power, others are nearby with gas stoves or battery-powered radios to help. That is what we saw on April 28, 2025 across Spain: citizens gathering in the homes of other kind citizens offering their resources to ease the blackout’s pain.

And that is because the Spanish people are naturally kind and empathetic. If what we have seen at the local or personal level seems appropriate, reasonable, and even logical, why not apply it at the provincial, regional, or national level? The fact that our rural towns organize their electricity independently of what’s decided in cities where we live, doesn’t make us any less of a united country. It does not make us any less brothers to be governed by different people. In fact, it might even be more efficient, because locals understand and solve local problems better than national governments. Governments do not know Salamanca as well as Salamancans do, so if they try to manage everything themselves, they will do it without the right information and at an unnecessarily high national organizational cost. This is the Austrian idea of the knowledge problem.

For now, the government will have to search for the fallen tree, the faulty station, or the location of the attack across nearly 500,000 km² of peninsular Spanish territory at a very high cost. If this had only happened in the Balearic Islands, the search area would be just 5,000 km² and the organizational costs much lower.

In conclusion, centralizing electricity management is probably a mistake. It makes us collectively vulnerable to a single failure or attack and also inefficient. We need to organize in a more distributed way and act as the Spanish people have already shown us, with kindness and care for others. Those are our values. But in the current situation, we have abandoned those values to let one person with power organize us however he wants. However, that person is a giant with feet of clay, because behind an incomprehensible political structure, he acts against what we believe is right.