We must understand the political ideas, history, and culture of the Founders’ generation.

Many American Founders, including our first four presidents, hoped to establish a national university that would educate statesmen for the new republic. During his second term, George Washington was presented with what seemed to be a golden opportunity to accomplish this goal—and rejected it on cultural grounds.

In 1794, the Swiss exile François d’Ivernois had written to John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, whom he knew from their years of diplomatic service in France. His home city of Geneva was suffering “convulsions” due to “the great political drama which now agitates Europe,” namely the French Revolution, whose terror had recently reached its nadir but whose fervor was still disrupting neighboring countries. D’Ivernois, himself “too much a republican” for the Calvinist Republic of Geneva but “too little a republican” for Revolutionary France, proposed a scheme “to transport into one of your Provinces our Academy [the University of Geneva] completely organised, and with it its means of public instruction.” At a stroke, it seems, Washington could have whisked away one of Europe’s premier universities and established it in the American republic.

Washington balked. “That a national University in this country is a thing to be desired, has always been my decided opinion,” but he doubted the ability of “an entire Seminary of foreigners, who may not understand our language,” to “be assimilated.” As Washington explained to Adams:

My opinion with respect to emigration is, that except of useful mechanics—and some particular descriptions of men—or professions—there is no need of extra encouragement: while the policy, or advantage of its taking place in a body (I mean the settling of them in a body) may be much questioned; for by so doing they retain the language, habits & principles (good or bad) which they bring with them; whereas, by an intermixture with our people, they, or their descendants, get assimilated to our customs, manners and laws: in a word, soon become one people.

The faculty of the University of Geneva were, so far as Washington could tell, highly skilled workers as well as politically moderate refugees with a long history of self-government. They were more closely aligned, culturally, religiously, and politically, to the American people than perhaps any other continental Europeans; only the Dutch and certain Germans would rival them in some respects. There was already a small and well-integrated Huguenot population in the United States, and anxieties about the monarchism and Catholicism of ancien régime France—or the radical revolutionary sentiment of the Jacobins—could hardly be felt toward the Genevan professors, with their centuries-long history of austere Calvinism and moderate republicanism. Nevertheless, this was a gulf too great. The “language, habits & principles” of Genevan Protestant republicans, if they were settled “in a body,” risked remaining a potentially unassimilable alien population to George Washington.

This historical anecdote, though obscure, is revealing of a larger and formerly uncontroversial fact. The American republic was established by a people descended from Englishmen that took its own culture seriously and strove to maintain its cultural core for expressly political reasons.

In 1775, Edmund Burke could state, flatly, that “the people of the colonies are descendants of Englishmen.” In 1787, John Jay could speak of the Americans as “a band of brethren,” “one united people” united by “the strongest ties”: namely, that they were “descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, professing the same religion, attached to the same principles of government, very similar in the manners and customs.” In 1835, Alexis de Tocqueville recognized the protagonists of the American story as “Anglo-Americans.”

Even J. Hector St. John de Crèvecœur, who described the American as “a new man, who acts upon new principles,” comprised of a “promiscuous breed” of cultures including “English, Scotch, Irish, French, Dutch, Germans, and Swedes,” emphasized the decisive role played by the more homogeneously English “eastern provinces” in establishing the “original genius” of America: the legal regime, cultural context, and social state to which all other immigrants were assimilated and by which all others were formed so that they became “that race now called American.”

When it came to questions of immigration, assimilation, and national identity, the principles of the Declaration of Independence, though central to the Revolution and the Founding, did not in the mind of George Washington override other, apparently more mundane concerns such as history, habits, and language. Washington did not need to inquire what the Genevan professors thought of the Declaration, or of “the idea of America.” It was enough for him to know that the Genevans were Genevan; and America, in any case, was not an idea. It was a nation, with its own cultural inheritance and, God willing, posterity. In the parlance of our times, “Heritage America” was a far more familiar and intuitive category to the American Founders than the “Proposition Nation.”

When terms like “Heritage America” are used today, they provoke great gnashing of teeth not only from the anti-American Left but also from many in the conservative establishment. Yet it was not so long ago that a mainstream academic like David Hackett Fischer (at Brandeis) could publish a detailed ethnographic study of the distinct British “folkways” informing American regional cultures.

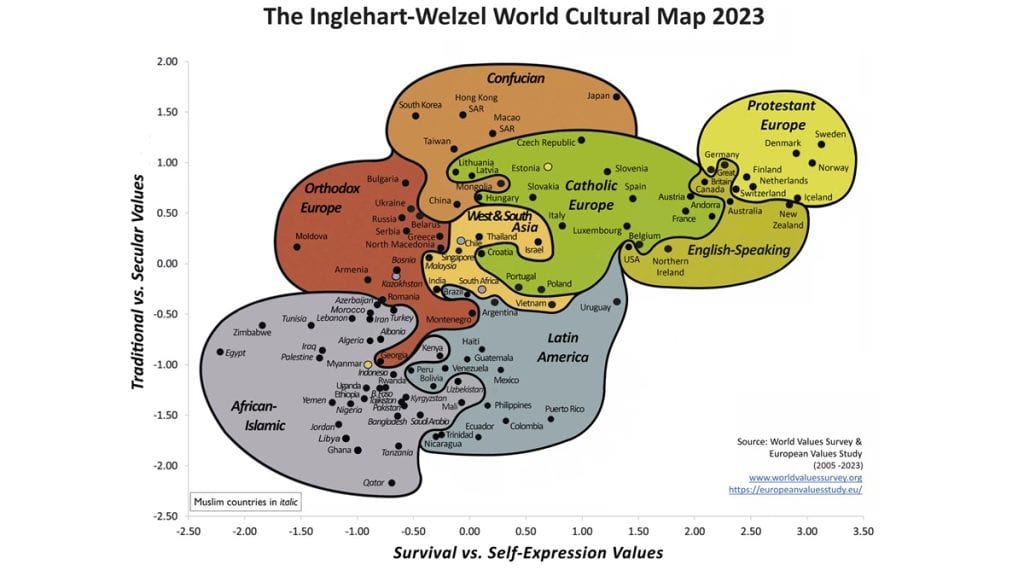

Likewise, Samuel Huntington (at Harvard) could write that the “American Creed” formulated by Jefferson was “the product of the distinct Anglo-Protestant culture of the founding settlers of America.” If social science is more your cup of tea, what is the World Values Survey’s Inglehart-Welzel World Cultural Map if not a quantitative and up-to-date version of the qualitative observation that America’s Anglo cultural foundation matters, and that an America that has absorbed waves of Catholic European and Latin American immigrants will be somewhat closer in its “values” to, well, the nations of Catholic Europe and Latin America?

All of which is to say, if we are to have an honest presentation of our national heritage as part of our celebration of the semiquincentennial of the Declaration of Independence, we cannot confine ourselves to recalling the historical events and teaching the political ideas of the American Founding. A third component, foundational to the others, is necessary if we are to rightly grasp the importance of the history and theory: the culture of the people who could, and did, produce such magnificent achievements as the American Revolution in general—and the Declaration of Independence in particular.

The Four Pillars

In what follows, I propose a framework for teaching the Declaration of Independence with these components in mind: culture, crisis, and creed, in that order. And I suggest a fourth, which is valuable though not as essential: commemoration, or the ways in which eminent Americans have reflected back on the Declaration in the intervening centuries.

Teachers of any level are invited to take up this framework and adapt it to their particular circumstances, expanding and contracting as needed. They can fit it to the level, character, and identity of their school and students, and supplement where necessary.

I recommend only primary sources from the Founding period, which are easily and freely accessible, that can stand more or less alone as teaching documents. Some historical context will be useful, but the documents themselves indicate with which incidents teachers and students should be familiar.

Of course, one could begin with American political sermons, or the early modern political philosophers, or Reformation divines, or Magna Carta, or even a survey of the classical political historians most beloved by our Founders—Polybius, Livy, and Tacitus—as deeper backgrounds to the American Founding. None of this would be time wasted. I am fortunate to teach at a college that supplies much of this context in courses that precede our study of America. But often, much of these earlier texts and themes cannot be included given the practical limits of the classroom. What I present is a brief syllabus, strictly focused on illuminating the Declaration of Independence, that will stand on its own if need be, and serve as a readily expandable core for more ambitious programs.

My basic contention is that the creed, the Declaration of Independence and the ideas it contains, is taught best when it is contextualized by the culture that produced it and the crisis that provoked it. As I understand it, the Declaration recommends this approach: its opening sentence promises to “declare the causes” that “impel” the American people to separate. Its next more famous sentence immediately continues: “We hold these truths to be self-evident.” This is as much a statement of identity—what we hold—as it is an introduction to the major premise of the syllogism that follows. The particular grievances against Parliament and King are the minor premise, which will result in the conclusion—a formal break from Britain and an acknowledgement that America is comprised of “Free and Independent States”—but only for those who take the truths of God-given natural equality and liberty and the concomitant theories of government and revolution to be “self-evident.”

Many peoples have endured tyranny; very few peoples have reacted in just the way in which the Americans did in the 1760s and ’70s. A people that did not accept these truths as their starting points very well might respond differently to the same stimuli: meekly submitting, for example, or reacting more violently at an earlier stage, or, if they lacked the peculiar habits of self-government that Americans had brought with them from England and developed over a century and a half, failing to organize themselves politically in response to the mounting threats to their liberty.

Following the Parliamentary overreach to raise funds after the French and Indian War, there would have been no “Imperial Crisis,” or at least not the same crisis, if the American people were not possessed by a “fierce spirit of liberty” attached specifically to “the question of taxing.” And without the crisis that began in 1763 and exploded at Lexington and Concord in 1775, there could have been no Declaration in ’76. If we wish to teach the “creed” contained in the Declaration of Independence, we need to understand something of the events that precipitated its drafting. And to understand both those events and the document itself, we must understand something about the culture that formed its agents, statesmen and minutemen alike.

For each unit, I list essential readings as well as possible supplements. Each unit in this syllabus could be taught in one day or several (especially if many supplements are added). I recommend reading the Declaration of Independence with the first set of readings and returning to it frequently through the subsequent units. I also strongly recommend reciting at least the first five sentences of the Declaration of Independence (beginning with “When, in the course of human events” and ending at “their future security”) each day of class.

Recitation and memorization have fallen out of favor in precisely the same era that progressivism repudiated our civilizational heritage and supplanted our self-governing republic with an expert-managed administrative state. It seems significant that the English idiom for “memorizing” is “knowing by heart”; and the “heart,” as C.S. Lewis explains, is another word for “the Chest”: the thumos or spiritedness by which man is man, and by which citizen is citizen. We are not going to recover the spiritedness of 1776 without educating “the American heart” as well as “the American mind.”

Crisis

What kind of culture produced the Declaration of Independence?

At several points, the Declaration distinguishes different kinds of peoples: the King is indicted for actions “totally unworthy [of] the Head of a civilized nation,” declared to be “unfit to be the ruler of a free people,” and blamed for inciting the “merciless Indian savages, whose known rule of warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions.” When such passages are noticed today, it is usually to condemn the Founders for their political incorrectness. Even conservatives, however, tend to pass over the important statement that is being made: there are such things as “civilized nations” and “savages,” that they conduct themselves differently in war and peace, and that if there is such a thing as “a free people,” there must also be such a thing as unfree or slavish peoples.

The Declaration also notes certain virtues possessed by the American people: they have exhibited “prudence” by approaching regime change cautiously rather than hastily. Their representatives have exhibited “manly firmness” in opposing the king’s violations. They have petitioned the King “for redress in the most humble terms.” They have addressed their “British brethren” with “the voice of justice and consanguinity.” Last but not least—indeed, framing the document as a whole—the authors of the Declaration have exhibited their piety toward God who has established the nations through his “laws of nature,” who has created men to be “endowed…with certain unalienable rights,” who continues to act in history as “the Supreme Judge of the world,” and who offers “the protection of Divine Providence” to those who place their faith in Him.

All of which raises the question: what kind of culture produced the Declaration of Independence? The following texts describe the American character as both spirited and orderly, jealous of its freedoms and well-equipped with habits and institutions by which the people exercise and secure their liberty.

Core Readings

- Second Continental Congress, Declaration of Independence (July 4, 1776), link

- Edmund Burke, “Speech on Conciliation with the Colonies” (March 22, 1775), excerpt

- J. Hector St. John de Crèvecœur, “What is an American?” (Letters from an American Farmer, Letter III) (1782), excerpt (pp. 66–70 in the Penguin edition)

- Letter: John Adams to the Abbé de Mably (January 15, 1783), excerpt from “Let me close this Letter, Sir,” to the end, describing the four institutions that shaped the American mind and heart

Supplemental Readings

- Mellen Chamberlain, “Remarks Before the Sons of the American Revolution” (April 19, 1894), excerpt on Captain Levi Preston and “the ultimate philosophy of the American Revolution” (from “When I was about twenty-one” to the end, pp. 248–251)

Crisis

The anti-monarchical elements of the American Revolution are frequently exaggerated, as if the political thought of the American Founding could be reduced to the screeds of that fresh-off-the-boat radical Thomas Paine. In fact, most of our Founders had a sober view of the relative strengths and weaknesses of every form of government.

The events leading up to the Declaration of Independence reveal that the quarrel with Britain is as much, and indeed at the start much more, a quarrel with Parliament as it is with the monarchy. King George is eventually indicted for 1) his failure to restrain a Parliament that is acting tyrannically toward the colonies, and 2) his active cooperation in Parliamentary hubris. But the problem begins with Parliament, which has arrogated to itself the right to legislate for a people that already have their own native legislative bodies: the Massachusetts General Court, Virginia’s House of Burgesses, and so on.

The quarrel with Parliament is evident in the Declaration itself, but it is best seen by tracing the run-up to independence. Here, we see the culture of the American people displayed in their fierce attachment to liberty, which was wedded to a growing capacity for continental political cooperation, legal reasoning, and powerful rhetoric in the Congresses of 1765, 1774, and 1775.

Also visible in these documents is the American willingness to shoot redcoats in order to remain within the Empire upon acceptable terms; to sacrifice luxuries in order to preserve their self-government; to maintain fraternal concerns for the threats to the liberty of their brethren back in Great Britain; to display their prudence and forbearance in slowly accepting the necessity of separation; and to shift seamlessly from appeals to the traditional “rights and privileges of Englishmen” to God-given “unalienable rights.”

Core Readings

- Stamp Act Congress, “Declaration of Rights and Grievances” (October 19, 1765), link

- First Continental Congress, “Declaration and Resolves” (October 14, 1774), link

- First Continental Congress, “Continental Association” (October 20, 1774), link

- First Continental Congress, “Address to the People of Great Britain” (October 21, 1774), link

- First Continental Congress, “Petition to the King” (October 26, 1774), link

- Second Continental Congress, “Olive Branch Petition” (July 5, 1775), link

- Second Continental Congress, “Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms” (July 6, 1775), link

- George III, “Proclamation of Rebellion” (August 23, 1775), link

- Second Continental Congress, “Resolution for Independence” (June 7, 1776), link

Supplemental Readings

- Second Continental Congress, “Washington’s Commission” (June 19, 1775), link

- Second Continental Congress, “Washington’s Instructions” (June 22, 1775), link

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “Paul Revere’s Ride” (1863), link

Creed

What is the argument of the Declaration of Independence?

A close reading of the Declaration is an immensely profitable exercise, especially after it has been placed in the immediate political context supplied by the earlier documents of the Continental Congress. It is also necessary to know what the Founders meant by key terms, above all “equality,” as well as “happiness”; political disputes in the intervening 250 years have largely concerned what such terms meant or ought to mean. This unit uses the Founders’ own words to illuminate these core ideas and correct the abuses that have been done to their ideas by later partisans.

Core Readings

- Second Continental Congress, Declaration of Independence (July 4, 1776), link

- James Wilson, “Of Man, As a Member of Society” (1791), excerpt on natural equality and inequality

- James Madison, “Property” (March 29, 1792), link

- Nathaniel Chipman, “Of the Nature of Equality in Republics” (1793), excerpt on inequality of property

- Letter: Thomas Jefferson to John Adams (October 28, 1813), excerpt on the natural aristoi (from “For I agree with you…” to “…may be irremediable”)

Supplemental Readings

- John Adams, Thoughts on Government (1775), excerpts (especially the opening paragraphs on the purpose of government, the “Militia Law” paragraph, and the “Laws for the liberal education of youth” paragraph)

- Thomas Jefferson, “Original Rough Draught” of the Declaration of Independence (June 1776), link

- Letter: John Adams to Timothy Pickering (August 6, 1822), excerpts (from “Cushing, t[w]o Adams’s and Paine…” to “…foreign connections” and “You enquire why…” to “…polished by Saml: Adams”)

Commemoration

How ought we commemorate the Declaration of Independence?

This unit could be multiplied endlessly to include whole swaths of political oratory and commentary from the last two and a half centuries, displaying how the Declaration has been used and abused, understood and misconstrued, in different centuries and decades. These readings focus on the Founders’ understanding of the moral and religious preconditions for free government, while broaching the question of what the particular achievement of the American people, expressed in universal terms, implies for our relation to the rest of the world—and whether, or in what way, we should expect the achievement of the Declaration of Independence to benefit other nations.

Core Readings

- Letter: John Adams to the Massachusetts Militia (October 11, 1798), link

- James Madison, “Spirit of Governments” (February 18, 1792), link

- John Quincy Adams, “Address on the Anniversary of Independence” (July 4, 1821), excerpt (from “The Declaration of Independence pronounced…” to “…the ruler of her own spirit”)

- Calvin Coolidge, “Speech on the 150th Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence” (July 5, 1926), link

Supplemental Readings