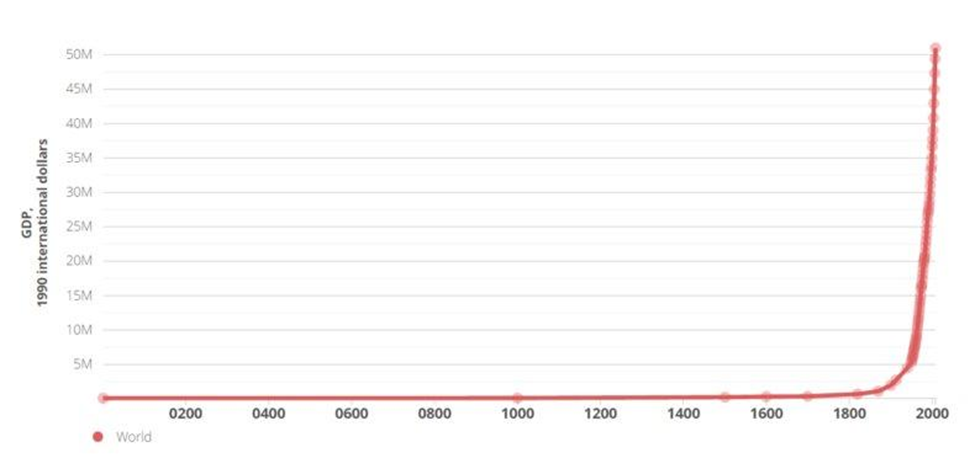

Many are familiar with the “hockey stick” graph of economic history (below) which details how, for all of human economic history, people lived on the equivalent of approximately $3 a day or less, however, there was an unprecedented change that took place around 1800—particularly in Europe then America—which led to an unprecedented advance in economic wealth and prosperity. Historically and economically, what needs to be explained is not poverty but wealth. There have been many attempted explanations as to why this took place, where this took place, and when this took place.

The Hockey Stick Graph

In much literature on this topic, this has become known as the “European miracle.” The conditions of the European miracle were not limited to Europe proper, but also to what might be termed the most successful extension of Europe, in which even greater economic prosperity generated—America. Historian Ralph Raico explains the European miracle in the following way,

The “miracle” in question consists in a simple but momentous fact: It was in Europe — and the extensions of Europe, above all, America — that human beings first achieved per capita economic growth over a long period of time. (emphasis added)

In this quote, Raico acknowledged that the “European miracle” applied to America—British colonies with the benefits of a shared Western-British heritage—but this article seeks to explore how the conditions that brought about unprecedented economic growth in Europe and Britain were magnified and intensified in America. Centrally, America inherited the core institutional framework of Europe (especially Britain) but refined and amplified it through greater decentralization, lower taxation, and more expansive freedoms.

What Made Europe Different

What brought about the European miracle? What made Europe different?

In short, decentralized political authorities, interjurisdictional competition, secure private property rights, rule of law, low and predictable taxes, freedom of exchange and contract, limited government, little to no regulatory regime, cultural respect for commerce and innovation, and a gradual ideological shift that honored markets and individual liberty. Mises wrote,

The East lacked the primordial thing, the idea of freedom from the state. The East never raised the banner of freedom, it never tried to stress the rights of the individual against the power of the rulers. It never called into question the arbitrariness of the despots. And first of all, it never established the legal framework that would protect the private citizens’ wealth against confiscation on the part of the tyrants. (emphasis added)

These institutions and conditions were not an automatic given, but were developed over centuries. Development economics P.T. Bauer wrote,

…it is misleading to refer to the situation in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe as representing initial conditions in development. By then the west was pervaded by the attitudes and institutions appropriate to an exchange economy and a technical age to a far greater extent than south Asia today. These attitudes and institutions had emerged gradually over a period of eight centuries. (emphasis added)

Europe represented the historical nexus of the influences of Greek classicalism, the ethic and cultural influence of Christianity, and decentralism since the fall of the Roman empire and inability for an empire to establish Continent-wide hegemony. Britain and Holland received those influences and institutions and further amplified them. Finally, Britain bequeathed America with a heritage of institutions, culture, values, and traditions that would continue to develop.

The Colonies: From Starvation to Economic Superiority

Despite early failures and desperation, even cannibalism, the American colonies experienced relatively rapid growth—even growing wealthier (and taller) than the British mother country. Writes Jeremy Atack and Peter Passell, A New Economic View of American History (p. 50),

By the time of the Revolution the American economy was at least ten times larger than it had been in 1690 and a hundred times larger than in the 1630s. Moreover, colonists in 1775 enjoyed a measurably higher material standard of living than their grandparents and great-grandparents. A per capita income averaging about $60—equivalent to perhaps $750 or so today [1994]—made them among the richest in the world at that time and provided some modest cushion against adversity. This is borne out in the height of Americans fighting in the French and Indian War. At five feet eight inches, colonists were much taller than those in the lower classes who had stayed behind in England… Moreover, probate records indicate that many Americans had managed to accumulate significant wealth holdings, further testimony to an excess of income over consumption in the long run…

After considering the tragic normalcy of starvation for most of human history, Deirdre McCloskey writes in Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can’t Explain the Modern World (p. 130) that, “Such desperate scarcities were broken in the New World of the British Americans, who ate better than their Old World cousins within a generation of the first settlements.”

American Decentralization and Polycentrism

Where Europe and Britain benefited from decentralization and polycentrism, America even more so. The American colonies had the benefit of great distance from the metropole and the non-policy policy of British “salutary neglect.” Further, the colonies were founded and developed separately with no single, central colonial government to rule them all. The colonies—far from viewing themselves as “one nation”—were resistant to and suspicious of any attempts to unite them under one government, fearing the loss of local control (e.g., the brief Dominion of New England [1686-1688] and the reaction to Franklin’s Albany Plan [1763]).

Distance from Britain and distance from other colonies ensured decentralization and limitations on enforcement. This necessitated that the colonies develop their own institutions. It also enabled a level of interjurisdictional competition between colonies—limiting tyranny, leading to experimentation, and pressuring colonies to liberalize.

Secure Property Rights

Secure, definable, and recognized property rights are essential to economic growth. The American colonies inherited this honor for property rights from the British. Of course, there were failures to uphold this standard consistently (e.g., experiments with communism, slavery, imperialism, etc.). That said, the West uniquely developed a cultural and legal respect for property rights. In America, following the Lockean tradition, the society largely recognized self-ownership and natural rights to life, liberty, and property. Aberrations, such as the contradiction of slavery—legal ownership of another self-owner—did exist, but it was the recognition of the validity of self-ownership and property rights that began to erode slavery in the West. Matthew Page Andrews in Virginia, The Old Dominion, vol. 1, said (p. 61),

…as soon as the settlers were thrown upon their own resources, and each freeman had acquired the right of owning property, the colonists quickly developed what became the distinguishing characteristic of Americans—an aptitude for all kinds of craftsmanship coupled with an innate genius for experimentation and invention.

Rule of Law/Minimal Regulatory Regime

Paradoxically and simultaneously, America had rule of law and the absence of a significant regulatory regime (i.e., absence of laws). Rule of law refers not to the sheer number of laws, but to a legal framework in which the government acts predictably, protects property rights, enforces voluntary contracts, and applies the law impartially. The American colonies had this, a fairly minimal regulatory environment, and little enforcement of existing regulations.

As mentioned, the non-policy policy of Britain toward the colonies was one of “salutary neglect,” that is, Britain benefited from prosperous colonies, therefore, while trade and commercial regulations existed, they were often unenforced and their violations ignored. Local markets operated with substantial freedom, often in defiance of British regulations (e.g., smuggling, unlicensed trade with non-British powers). Rosenberg and Birdzell, in How the West Grew Rich, write, “The enforcement of the Navigation Acts had been lax up until 1763, and a prosperous American merchant marine had developed, much of it illegally” (p. 93). According to Adam Smith, why these regulations were little respected was because of a qualitative distinction between natural law and regulations that restricted natural law,

…a person [smuggler] who, though no doubt highly blameable for violating the laws of his country, is frequently incapable of violating those of natural justice, and would have been, in every respect, an excellent citizen, had not the laws of his country made that a crime which nature never meant to be so. In those corrupted governments where there is at least a general suspicion of much unnecessary expence, and great misapplication of the public revenue, the laws which guard it are little respected. (emphasis added)

Interestingly, the nature of maritime trade itself helped break the feudal system over centuries and developed individualism. Rosenberg and Birdzell again write, “So it was during the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, maritime trade was at once a major field of economic growth and a field intractably resistant to medieval principles of political controls” (p. 95).

Low and Predictable Taxes

While several others could be mentioned—especially ideological transformation—the last institutional factor of colonial America’s growth explored here is that of the conspicuous absence of taxes. Historian Paul Johnson explains that “the American mainland colonies were the least taxed territories on earth. Indeed, it is probably true to say that colonial America was the least taxed country in recorded history. Government was extremely small, limited in its powers, and cheap.” American living standards were so high because “people could dispose of virtually all their income.” In fact,

Until the 1760s at any rate, most mainland colonists were rarely, if ever, conscious of a tax-burden. It is the closest the world has ever come to a no-tax society. That was a tremendous benefit which America carried with it into Independence and helps to explain why the United States remained a low-tax society until the second half of the twentieth century. (emphasis added)

Alvin Rabushka—in his 968-page Taxation in Colonial America—explains that from 1764 to 1775,

…the nearly two million white colonists in America paid on the order of about 1 percent of the annual taxes levied on the roughly 8.5 million residents of Britain, or one twenty-fifth, in per capita terms, not taking into account the higher average income and consumption in the colonies. (p. 729)

In context, on the eve of the Revolution, “British tax burdens were ten or more times heavier than those in the colonies.”

It was for the above reasons—to which we could add others—that the “American miracle” was the European miracle on steroids. Where Europe, especially Britain, benefited from ideological transformation, decentralized governments, property rights, rule of law, limited government, and low taxes, the American colonies amplified all these factors.