It’s keeping young families from owning homes.

President Trump began the first full week of 2026 with several announcements, one of which was likely to get missed in everything that’s been taking place: he committed his administration to “ban[ing] large institutional investors from buying more single-family homes,” because “[p]eople live in homes, not corporations.” A fair enough observation.

However, according to the Brookings Institution, large institutional owners account for less than 3% of home ownership nationally. Yet home prices are still absurdly high.

Affordability is a key topic for young people who lived through the post-CARES Act inflation and resent many of their elders for owning homes they don’t think they’ll ever be able to afford. Zohran Mamdani soared into the New York City mayor’s office in part because he repeatedly spoke on this issue. While it is a positive sign that the Trump Administration is looking to tackle exorbitant home prices for young Americans, its ban on institutional investing may miss the forest for the trees, that great expanding forest being the Federal Reserve.

Throughout its history, the Fed has made it increasingly harder for young people to own homes. It has so badly failed that the normal means of relief for mortgage seekers have made the affordability problem even worse. Russ Greene has insightfully argued that the entitlement system is rigged against young people in favor of the old. Monetary policy is similarly rigged against the young.

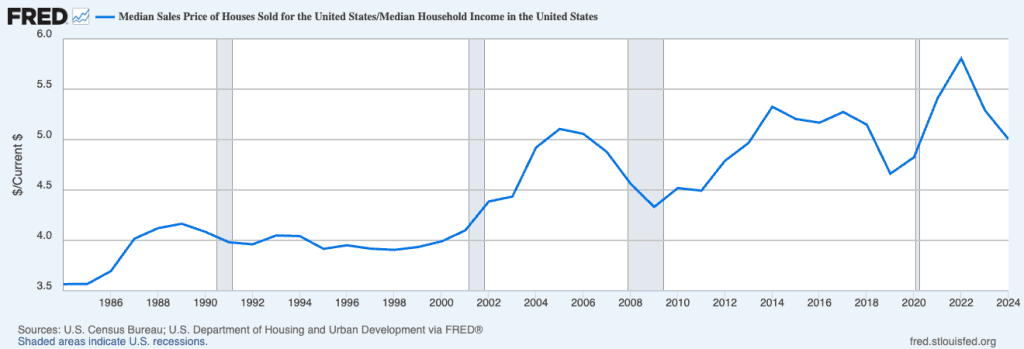

One can begin by looking at the median home price today, but that alone tells us little about inflation. A good measure to show how unaffordable homes have become is the ratio of the median home price to the median household income. An increase in this ratio tells us that the median price of a home is growing faster than the income a median household brings in. The data on household income only began to be collected in 1984, limiting our time range, but the information is still revealing.

In 1984, the median household could purchase a home for three times its annual income. This ratio continued ticking upwards to a peak of 5.9; today, it rests at 5.0. Rising median worker income has not narrowed the gap, as home prices continue to rise even faster. The median first-time home buyer is now 40 years old, hardly the youthful buyer pictured in the American dream.

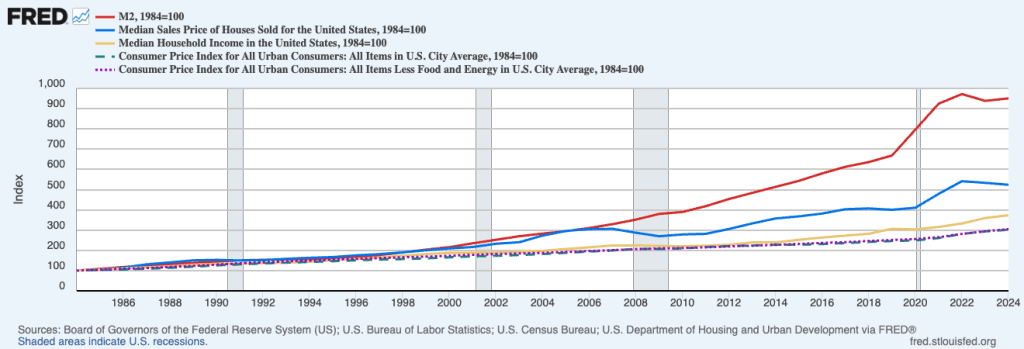

Austrian School economists like Ludwig von Mises and Murray Rothbard long emphasized that inflation does not affect all areas of the economy proportionally. It is an increase in the money supply rather than being a measure of an amorphous price level. Every exchange changes the prices of every other good, as well as money, so attempts to measure baskets of goods fail to show an increase in the overall price level.

Money enters the economy at specific times, whether from the hands of counterfeiters, those who receive government funds, or the central bank. Money trickles down as prices continue to rise the further the new money gets from its origins. The result is a transfer of wealth, real goods, and assets into the hands of the first receivers of money and away from those furthest from the monetary spigot. Scottish economist Richard Cantillon first observed this phenomenon with increases in the supply of gold, which has since been dubbed the Cantillon effect.

The first receivers of new money, often in the form of newly created credit in the banking system, spend it on assets like homes and stocks. These assets tend to outpace the Consumer Price Index (CPI), meaning that the owners will acquire equity that can be used for further loans.

When the M2 money supply is indexed against the CPI, it is obvious that the money supply has increased far more since 1984 than the typical price index. So where did the money go? We can see the answer by observing the median household income and median home price. Income has certainly risen and has stayed above the CPI, meaning that real income is growing in some sense. But it has not grown nearly as much as the median home price, which has increased significantly above the price index.

Easy money policies beginning just before the dot-com crash decoupled labor income from housing. As the Federal Reserve played with price controls on interest rates, keeping them lower than they otherwise would be, the money supply continued to accelerate and decouple from the CPI, bringing housing prices with it. Money flowed into home values, though declining at times such as in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, pushing them up and widening the gap between income and housing.

The Federal Reserve doesn’t seem to be willing to prick a housing bubble now, as destroying home equity is a politically unpopular policy. When home equity becomes a retirement plan, it becomes incredibly unpopular to alter it. Furthermore, mortgage-backed securities on the Fed’s (and large private banks’) balance sheets mean that the real value of those securities will decrease if the Fed raises interest rates.

Even when the Fed has attempted to cut interest rates to provide mortgage relief for new homebuyers, the mortgage rate has gone up regardless. The Federal Reserve’s inability to get the year-to-year inflation rate down to 2% has forced banks to price in an inflation premium so that they don’t lose money.

The Fed’s easy money policy has resulted in money flowing into the home equity of current homeowners, many of whom, as Russ Greene notes, are occupying homes much larger than their needs.

New homeowners are unable to get mortgages at low interest rates and cannot save because inflation penalizes saving money. They can’t even afford mortgages at high interest rates because the values of those homes are propped up by the Federal Reserve. If the Fed abandons its 2% target even for a 3% target, the money supply will increase even faster and home prices even more.

Rather than focus on bringing down inflation, the Fed has done what every bureaucracy does: focus on its own needs such as renovating its own buildings, even when the costs are higher than original projections. Chairman Jerome Powell’s statements to Congress have earned him an investigation by the DOJ for possible perjury before Congress. Congress seems much less willing, however, to interrogate Powell on the Fed’s tasked policies.

A longer mortgage term like the controversial proposal of a 50-year mortgage will not solve the problem.

So what can be done?

The answer is that inflation cannot be tolerated. Financialization is a product of easy money and inflationary policies. It artificially props up home prices and makes homes less affordable for young people. A naturally deflationary policy allows the accumulation of savings, and thus real capital, which would increase the wages of the median household member. Savings can be used to buy a home, which in a non-inflationary market might very well fall in real price like televisions, computing, and other modern goods have.

What was formerly the cornerstone of the American dream has begun to look unattainable to most young people. When conservatives and libertarians paint the current system as a “free market” and ignore the effects of the Federal Reserve’s policies, they foster resentment toward markets. We owe it to them to stop rigging the system against their interests.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.