A buzzword once confined to anarchist zines has suddenly become ubiquitous in the American liberal lexicon: “mutual aid.” Certainly, it was bandied about in online Leftist spaces at the height of the Covid pandemic, but according to Google Trends, searches for it have surged to an all-time high since the anti-ICE battle went mainstream this winter.

The problem is that even with all the Googling, no one has a definitive answer on what the hell mutual aid actually means. In activist circles, it’s often tacked onto the stock list of self-descriptions, recited as part of their Leftist CVs: I do art, activism, political organizing, and mutual aid, which is like renaming the same job four times on a resume to sound busier. These days, mutual aid is usually a synonym for organized do-goodery or small-scale politics, but not always.

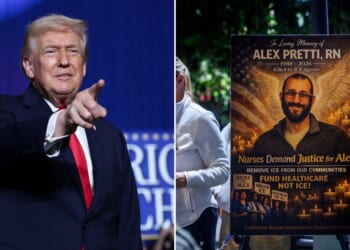

It’s invoked to describe anything from “craftivism” projects like distributing “Melt the ICE” knitted hats, swapping casseroles, and borrowing a power drill, to running abortion access networks and organizing rapid-response teams for immigration raids. It can apparently include running a homeless shelter in Philadelphia, handing out free condoms and fentanyl test strips in San Francisco, or distributing Indigenous Justice fact sheets for the “Land Back” movement in the Twin Cities. Also, don’t forget mutual-aid GoFundMe campaigns for sex workers or the Bruce Springsteen and Bon Iver benefit concert to raise money for the families of Renee Good and Alex Pretti, which, of course, was named the Mutual Aid Benefit Concert.

What all of these disparate acts have in common is Left-of-center framing. Mutual aid is a woke rebrand of two very old human impulses: charity and neighborliness. Those terms sound too much like conformist bourgeois values, and to Left-libs, the act of helping can’t simply be helpful; it must be subversive. Everything has to be seen as a radical act of resistance against, well, what ya got? Federal overreach. MAGA. Capitalism. White supremacy. Check. Check. Check.

What’s most grating about mutual-aid discourse isn’t the helping itself — which is mostly good — but the historical amnesia around it. The way activists talk, you’d think Americans only discovered the concept of neighbors helping neighbors sometime around 2020, thanks to, say, the Instagram reels of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. In reality, America was built on dense webs of voluntary association and community aid long before anyone sewed “Abolish ICE” on a tote bag. Just ask Alexis de Tocqueville, who — nearly 200 years ago in his book Democracy in America — marvelled at the way Americans built their own associations and institutions as a bulwark against elite greed. “In democratic peoples, associations must take the place of the powerful particular persons whom equality of conditions has made disappear,” De Tocqueville wrote. He observed a society where, if a road needed fixing or a barn needed raising, men didn’t wait for a grant or a website; they simply came together and took action.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, union halls, fraternal orders, churches, ethnic societies, volunteer fire companies, and informal neighborhood networks once did much of what today’s organizers claim as a radical innovation and often went way further: they pooled money, fed the hungry, cared for the sick, buried the dead, and kept communities afloat when the state was distant or indifferent. Contemporary activists like to cite the Black Panthers’ Free School Lunch program in Chicago in the 1960s as their intellectual lodestar, but a better comparison might be the infrastructure of mutualism built by European immigrant communities in the same place decades earlier.

When the Czechs, for instance, turned Chicago into the third biggest Czech community in the world behind Prague and Vienna, they constructed hulking structures called sokols where you could attend educational classes, listen to lectures, visit libraries, see choral groups, theater, and other entertainment — all in the same building — for free, if you could speak the native tongue. These pre-welfare-state communities also looked after the poor and provided informal banking and insurance, all without state intervention. There was no “Solidarity, not Charity” slogan plastered on the walls because the distinction was self-evident: you weren’t “serving” a client; you were sustaining your own people. Even as these tight-knit immigrant cultures assimilated, a strong sense of neighborliness and charity remained throughout the 20th century.

“Mutual aid is a woke rebrand of two very old human impulses: charity and neighborliness.”

This instinct has dulled in the 21st century; what’s been deemed the “anti-social century,” due to hyperindividualism, the death of in-person community, and the NGOing of America that turned charity into Charity™. But that doesn’t mean it’s dead — far from it. If we strip away the radical chic and the academic jargon, the biggest mutual aid project of this year didn’t happen at a protest or a community meeting; it happened on just about every street and city block during this winter’s historic snowstorms. People shoveled each other’s driveways, dug out or jump-started cars in sub-zero temperatures, and checked on the elderly. On my street, a 30-something man named Joe was outside all day after 14 inches of snow fell, shoveling his entire block. Another elderly man took turns heave-ho-ing cars stuck in snowbanks. Shoveling ice, not protesting ICE, was “mutual aid” in its truest and most effective form — neighbors, family, and friends looking out for one another without needing to call it resistance (unless that meant resisting the bad weather). You don’t need to “center the voices” of the cold; just grab a shovel, and suddenly three other people grab their shovels too. That’s how social norms work.

There’s also a class story hiding in the mutual-aid discourse. Much of what now exists under the banner of mutual aid is, in practice, the middle or upper-middle classes assisting the working poor or what Marx once called the lumpenproletariat, often mediated through NGOs, activist collectives, or social media campaigns. This is presented as horizontal solidarity, but the structure remains vertical. The resource-rich help the resource-poor. Again, there’s nothing particularly wrong with that. But what’s odd is the insistence that this arrangement is fundamentally different from charity, as if renaming the relationship dissolves the underlying asymmetry. It doesn’t. It just changes the story we tell ourselves about it.

That story matters because language shapes expectations. When mutual aid is framed as resistance, ordinary acts of care risk being devalued unless they’re politicized. Helping your neighbor move a couch becomes morally thinner than helping a stranger as part of a branded campaign called something like Seat Your Community. Clearing snow becomes less meaningful than staffing a mutual-aid table with a logo. This is a perverse incentive structure. It nudges people away from the kinds of thick, local bonds that actually sustain communities and toward thin, performative gestures that travel well on social media.

And vibes, like snowdrifts, eventually melt. When the political moment passes, as the current ICE #Resistance will inevitably, so does the attention, and with it the care. Neighborliness, by contrast, is boringly durable. It doesn’t spike on Google Trends, but it persists across decades. Unless your local Food Not Bombs chapter is actually stopping bombs rather than just cooking meals for people in need, that’s not radical. That’s called becoming your grandmother. And thank God. The revolution can wait; the driveway cannot.