The global economy continues to slow and stagnate as GDP numbers in the US, UK, Germany, and Japan all show ongoing economic weakness.

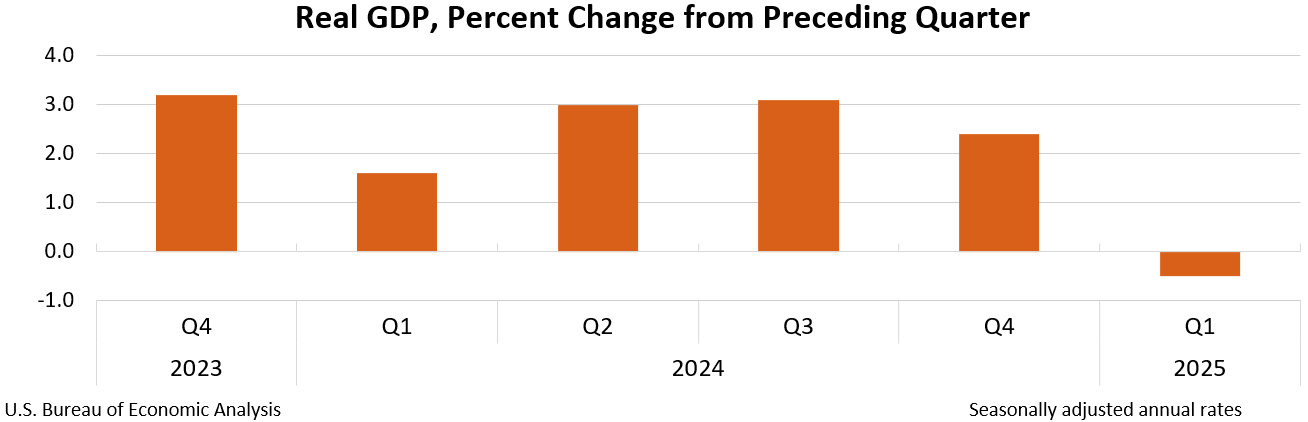

Today, the US Bureau of Economic Analysis released its third revision for the first quarter, with the US GDP falling by 0.5 percent during the first quarter. According to the BEA press release:

Real gross domestic product (GDP) decreased at an annual rate of 0.5 percent in the first quarter of 2025 (January, February, and March), according to the third estimate released by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. In the fourth quarter of 2024, real GDP increased 2.4 percent.

The decrease in real GDP in the first quarter primarily reflected an increase in imports, which are a subtraction in the calculation of GDP, and a decrease in government spending. These movements were partly offset by increases in investment and consumer spending.

Real GDP was revised down 0.3 percentage point from the second estimate, primarily reflecting downward revisions to consumer spending and exports that were partly offset by a downward revision to imports.

This latest downward revision is what we’d expect to see after months of the Federal Reserve reporting that its own surveys shows that 6 out of 12 Federal Reserve districts are experiencing slowing or flat economic activity. (The Richmond Fed manufacturing activity index, for example, has been in negative territory for more than two years. )

Moreover, the Conference Board Leading Economic Indicators has been accelerating downward:

The Conference Board Leading Economic Index (LEI) for the US ticked down by 0.1% in May 2025 to 99.0 (2016=100), after declining by 1.4% in April (revised downward from –1.0% originally reported). The LEI has fallen by 2.7% in the six-month period ending May 2025, a much faster rate of decline than the 1.4% contraction over the previous six months.

Given all this, there has been no reason to expect robust growth during the first quarter, especially since government spending—a key component of GDP measures that inflates overall growth measures—somewhat moderated during the first quarter.

The US GDP also reflect a global trend toward stagnation in economic growth. For example, Japan’s economy contracted during the first quarter this year. In spite of recent upward revisions, the Japanese economy was still in negative territory according to new data out of Tokyo released on Wednesday:

Gross domestic product shrank an annualised 0.2% in the three months through March 31…

Versus the previous quarter, the revision translates as flat in price-adjusted terms compared with an initially estimated 0.2% contraction.

The revision does little to allay analyst concern that economic growth was losing momentum even before U.S. President Donald Trump implemented his so-called reciprocal tariffs on April 2.

“It wasn’t a revision that changed our view on the overall economy,” said economist Uichiro Nozaki at Nomura Securities.

Meanwhile, the German central bank last month predicted more stagnation for the German economy:

The German Bundesbank expects the economy to stagnate in 2025 after two years of recession in the country. This is stated in the new six-month forecast of the central bank, released at the end of last week.

Thus, the regulator has downgraded its December expectations, according to which Germany’s GDP growth was expected to reach 0.2% this year.

This comes after two years in a row of a contracting economy in Germany, with GDP declines in both 2023 and 2024.

The UK has been a little behind this trend, but is seeing similar contraction in the second quarter of 2025. For example, the UK government released today new data showing the UK economy has contracted for the second month in a row:

The latest monthly growth figures from the Office for National Statistics showed U.K. gross domestic product (GDP) contracted 0.1% month-on-month in May. Analysts polled by Reuters had expected a 0.1% expansion.

Weakness was concentrated in production output, down 0.9%, and construction, which fell 0.6%. The figures will come as a blow to Finance Minister Rachel Reeves, who has made rebooting economic growth and reducing the U.K.’s budget deficit her core aims.

The latest data follows a contraction of 0.3% in April, when domestic tax rises were introduced…

Much of the narrative around this focuses on declines in international trade brought about by the Trump administration’s chaotic efforts to impose new taxes on imports into the United States. This is no doubt partly responsible for the economic slowdown, but the weakening economy has been in cards for years thanks to the immense burden placed on the private economy by years of runaway monetary inflation and government spending.

Thanks to the rapid rise in government spending that occurred during the covid panic and afterward, the amount of government debt has skyrocketed since 2020, crowding out private investment, and putting upward pressure on interest rates. Meanwhile, government has accelerated—with no sign of any change in trajectory under the Trump administration. This drives up prices for private businesses that are forced to compete with tax-funded government enterprises for resources, labor, and land. This all drives down private-sector productivity.

Unfortunately, much of the government spending—which is siphoning off resources from the private sector—is counted as GDP growth, thus papering over the slow-motion strangulation of the private sector by monetary inflation, deficits, and federal spending. In spite of the fact that federal spending is counted as GDP, economic growth cannot be sustained beyond the short term by economic policy that relies more and more on government activity as a replacement for private sector growth. (Note, for example, how half of June’s job growth was government jobs.)

This ultimately leads to a growing tax burden either in the form of normal taxation or in the form of the inflation tax.

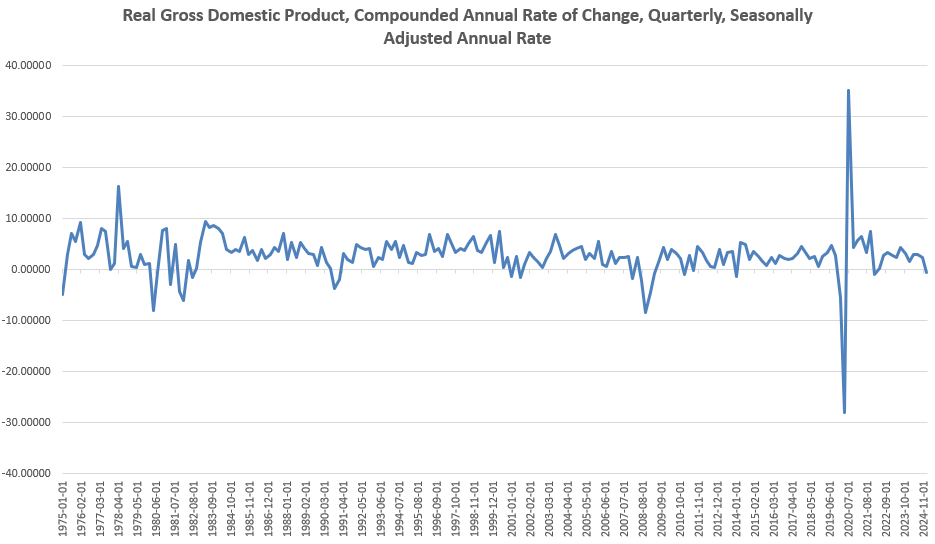

This is all avoidable, and the economic slowdown is not due to intractable forces inherent to developed economies as some economists, like Larry Summers, claim in many of their explanations of “secular stagnation.” Since the Great Recession, the US economy has been increasingly weak thanks to a transition to inflation-based growth, growing deficits, and a rising regulatory burden. Those quarters that do report higher than usual levels of growth are fueled by monetary inflation. These “high-growth” quarters—such as the post covid quarters of 2021—are then followed by rising price inflation and falling real wages.

Unless the current administration acts to reverse this ongoing period of easy-money fueled spending, deficits, and asset price inflation, we can expect to see ongoing problems with stubborn stagnation in the private sector.