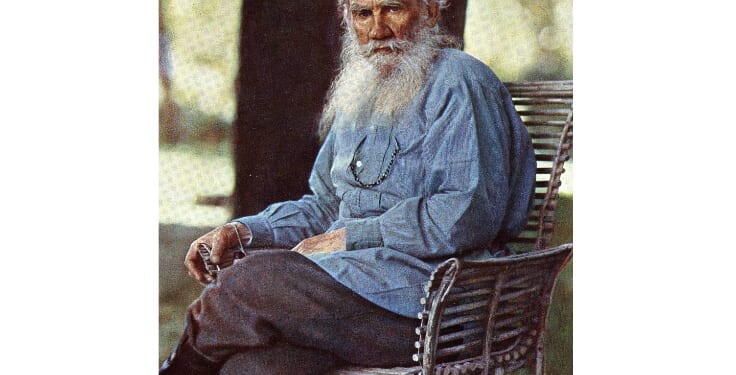

Leo Tolstoy is the greatest writer in the Western world—greater, yes, than Shakespeare, Dante, Dickens, Dostoyevsky, and Proust. In evidence I would submit his two masterpiece novels War and Peace (1867) and Anna Karenina (1878), and 20 or so magnificent novellas and short stories, among them “The Death of Ivan Ilych,” “The Kreutzer Sonata,” “Father Sergius,” “Hadji Murad,” and “Master and Man.”

Resurrection (1899), now reissued in a handsome Everyman Library edition, is Tolstoy’s last novel. Ostensibly it is a love story. I say ostensibly because the love in the story doesn’t quite come off. The book’s heroine, Katerina Maslova, remains shadowy through the novel’s nearly 500 pages; and the twists and turns of its hero, Prince Dmitry Ivanovich Nekhlyudov, aren’t always quite creditable. A novel with the grandest of intentions, Resurrection, alas, fails in the way only a great writer could write a failed novel.

Resurrection has no fewer than 93 named characters, and perhaps quite as many characters—family aristocrats, peasant-prisoners, various bureaucrats—who go nameless. The plot begins simply enough. Katerina Maslova works as a maid for two of Nekhlyudov’s aunts. She is an attractive young woman, and he is as much taken with her as she with him. The flirtation between them is not consummated until a few years later, when Nekhlyudov returns from his military service. He then seduces her, and she, though he does not know it, becomes pregnant. She loses the baby, and, owing to her pregnancy, also loses her job with Nekhlyudov’s aunts. Katerina soon ends up in an “establishment,” for which we read bordello, working as a prostitute.

Fast forward (why do we never slow backward?) a few years, and Katerina Maslova is given a potion to put in the wine of a pestiferous client that will put him asleep. What she doesn’t know is that the potion is poisonous, given to her by a couple who have robbed the man. Katerina is indicted for his murder, imprisoned, and put on trial, where she is found guilty and sentenced to exile and hard labor in Siberia. On the jury for her trial sits Nekhlyudov, who realizes what he has brought about in seducing the young Katerina. Tolstoy writes:

“No, it cannot be,” said Nekhlyudov to himself; and yet he was now certain that this was she, that same girl, half ward, half servant, with whom he had once been in love, really in love, and whom he had seduced in a moment of delirious passion, and then abandoned and never again brought to mind—because the memory would have been too painful, would have convicted him too clearly, proving that he who was so proud of his integrity had treated this woman in a revolting, scandalous way.

Nekhlyudov vows to himself to make it all up to her by proving her innocence and eventually marrying her.

This is all very well, the donnée of a strong plot, except in Resurrection Tolstoy isn’t primarily interested in plot. In this, his last novel, the great novelist turns social polemicist, the artist turns prophet. Toward the end of his life, Tolstoy devoted himself to criticizing Russian institutions in such books as Why Do Men Stupefy Themselves? This unfortunately is the Tolstoy who predominates in Resurrection.

Nekhlyudov’s negligent behavior, for example, is written off to his years in the military. Tolstoy himself fought in the Crimean War (1853-56), but in Resurrection he treats the military throughout with contempt. We learn, for example, that before his military service, Nekhlyudov “had been an honest, unselfish lad, ready to sacrifice himself for any good cause,” but now “he was a depraved, refined egotist, caring only for his own enjoyment.” Tolstoy writes: “Military life in general depraves men. It places them in conditions of complete idleness, that is, absence of all rational and useful work; frees them from their common useful duties, which it replaces by merely conventional duties to the honor of the regiment, the uniform, the flag; and while giving them on the one hand absolute power over other men, also puts them into conditions of servile obedience to those of higher rank than themselves.”

Tolstoy is no less hard on the Russian court system, which he characterizes as “this comedy no one needed.” He describes judges bored by their own proceedings, their minds not on the business at hand but on meeting with mistresses later in the day. He singles out an assistant prosecutor who “was very stupid by nature, but besides this he had the misfortune of finishing school with a gold medal and receiving a reward for his essay on Servitude when studying Roman Law at the university, and was therefore self-confident and self-satisfied in the highest degree (his success with the ladies also conducing to this) and his stupidity had become extraordinary.” An advocate Nekhlyudov has hired to marshal an appeal for Katerina tells him of the current-day Russian courts that “they are just officials, only troubled about pay. They get their salaries and want more, and there their principles end. They will accuse, judge, and sentence anyone you want.”

But Tolstoy reserves his greatest contumely for the Russian prison system. He sends Nekhlyudov on what seems an endless round of visits to prison in his attempt to communicate with Katerina, each time coming away with darker and darker views. Of the prisoners he writes: “Terrible was the disgrace and suffering cast on those scores of guiltless people simply because something was not written on paper as it should have been. Terrible were the brutalized jailers, whose occupation is to torment their brothers, and who were certain that they were fulfilling an important and useful duty.” Of the people who run the prisons, Nekhlyudov thinks: “Perhaps these governors, inspectors, policemen are needed; but it is terrible to see men deprived of the chief human attribute, that of love and sympathy for one another.” The prisons suffocate the love that is natural to humans; or, as Nekhlyudov holds: “If once we admit—be it only for an hour or in some exceptional case—that anything can be more important than a feeling of love for our fellows, then there is no crime which we may not commit with easy minds, free from feelings of guilt.”

All this crushing criticism of Russian institutions reduces the reader’s interest in the love between Nekhlyudov and Katerina Maslova. Spoiler alert: In the end the two do not marry. Tolstoy’s explanation is: “She loved him, and thought that by uniting herself to him she would be spoiling his life. By going with Simonson [a prisoner introduced late in the novel] she thought she would be setting Nekhlyudov free, and she felt glad that she had done what she meant to do, and yet suffered at parting from him.”

Instead the novel ends on Nekhyludov’s reading of the Gospels, and determination to live out his life according to a distillation of five commandments among them. Even Chekhov, whose admiration for Tolstoy was unstinting, found this less than convincing: “To write and write, and then suddenly to throw it all away on a piece of scripture is a little too theological.” And so it feels.

Romain Rolland among others read Tolstoy himself into the character of Dmitry Ivanovich Nekhlyudov, though Nekhludov is supposed to be in his 30s during the time of the novel and Tolstoy was already in his 70s. Henri Troyat, Tolstoy’s most recent biographer, felt that in Resurrection Tolstoy “never wrote with greater violence and less ‘artistry.’ He takes even less pains than usual with his style because he is not trying to tell a story; he is trying to stigmatize those who are responsible for the present plight of society.”

Tolstoy told Prince Dmitry Aleksandrovich Khilkov, a disciple, that “just as nature has endowed certain men with a sexual instinct for the reproduction of the species, she has endowed others with an artistic instinct, which seems to me equally absurd and equally imperious … I see no other explanation for the fact that an old man of seventy who is not entirely stupid should devote himself to an occupation as futile as writing novels.” Troyat suggests Tolstoy was merely feigning self-belittlement here. But I wonder if, having grown impatient with the deep but slow working of literature, he wasn’t entirely serious. I can think of no other explanation for why, in Resurrection, the world’s greatest storyteller chose not to tell a truly engaging story.

Resurrection (Everyman’s Classics Library Series)

by Leo Tolstoy

Everyman’s Library, 552 pp., $34

Joseph Epstein is the author, most recently, of The Novel, Who Needs It? (Encounter Books).