Donald Trump’s diplomatic high-wire act never stops. The ceasefire between Israel and Hamas demands constant attention. The war between Russia and Ukraine is nowhere near a settlement. The trade war with China toggles off and on. U.S. forces target drug smugglers linked to Venezuela and Colombia.

As if all that weren’t enough, America risks alienating a key ally in our strategic competition with China.

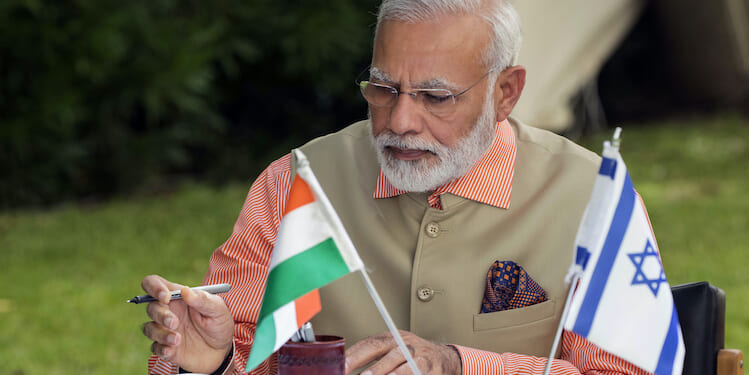

The friend is India. A recent visit here as part of a delegation organized by the Hudson Institute and the India Foundation brought home the extent of the damage from tariffs, immigration restrictions, and most important, dealings with Pakistan. The Indian government, led by prime minister Narendra Modi, is struggling to understand and manage Trump’s sudden reversals, while the Indian public feels betrayed. The general sense is that the two democracies will weather the storm—but only if the United States comprehends the significance that India places on Pakistan, and acts accordingly.

Close ties between America and India weren’t and aren’t inevitable. They’re the result of strategic decisions on both sides. And they don’t come easily. After winning freedom from the British in 1947, India acted as the conscience of the Non-Aligned Movement, navigating an independent and often ambivalent course between West and East, between the Free World and the Communist bloc.

America found a more willing Cold War partner in Pakistan, the Muslim nation born out of partition from India, and against which India has fought four wars in 78 years. Pakistan served as an anti-Soviet check in South Asia. It acted as an intermediary between the United States and China. It was the staging ground for U.S. support for the mujahedeen fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan. The result was mistrust between America and India, a rare phenomenon for two countries that share common values, such as freedom and pluralism, as well as democratic institutions.

Things began to change at the approach of the millennium. The Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, around the time India opened its economy to free enterprise and foreign investment. Indian migration to the United States grew. And India became central to the back-office operations of major US corporations.

When both India and Pakistan joined the nuclear club in 1998, the subcontinent’s importance became undeniable. Still, habits are hard to break. America continued its tilt toward Pakistan.

President George W. Bush inaugurated an era of good feelings. India was a natural fit for a president whose term was defined by a global war on terrorism and championing democracy. Bush upgraded relations with India, and our two nations signed a civil nuclear cooperation agreement. As part of the deal, India separated its military and civil nuclear programs, agreed to cooperate with the International Atomic Energy Agency, and shared technology with the United States.

Barack Obama continued the trend, in his diffident way. He visited India twice, commenced a strategic dialogue, supported India’s bid for a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, and ordered the attack on Osama bin Laden’s Pakistani hideout. With Russia stumbling, radical Islam spreading, and China rising, India replaced Pakistan as the focus of America’s regional efforts.

President Trump turbocharged relations. In his first term, Trump took a hard line against India’s other longtime rival, the People’s Republic of China. To counter China’s regional ambitions, Trump established the Indo-Pacific “Quad” of India, Australia, Japan, and the US. And he got along famously with Modi, whose political style of nationalist populism complements Trump’s. The two leaders walked hand in hand at “Howdy Modi” and “Namaste Trump” rallies in Houston and Ahmedabad, the capital of Gujarat, Modi’s home state.

“Everybody loves him, but I will tell you this: He’s very tough,” Trump said, aughing at Motera Stadium in Ahmedabad, as Modi smiled nearby.

The personal friendship and budding alliance was expected to resume when Trump returned to the White House. And for several months, it did. Modi was among the first foreign leaders to meet with Trump in the Oval Office. JD Vance visited India with his wife Usha, the daughter of Indian immigrants, and their three children. A US-India trade agreement looked imminent. Trump was well positioned to build on the accomplishments of his first term, leveraging the US-India relationship as a hedge against Chinese expansionism.

That didn’t happen. Instead, Trump imposed a series of measures that frayed ties at the worst possible moment. A 25 percent tariff on “Liberation Day.” An additional 25 percent tariff for purchasing Russian oil. Restrictions on student visas. A $100,000 tax on H1B visas. And most damaging, a renewed tilt toward Pakistan after a four-day clash over an Islamist terror attack in the spring, as Trump hosted Pakistan’s army chief Field Marshal Asim Munir for a White House lunch and entertained Pakistan’s offer of selling America rare earth minerals.

The senior officials, thinkers, and business and cultural elites I met in India drew a distinction between policy disputes and strategic realignment. They were confident that India and the U.S. would come to terms on purchases of Russian oil, on trade that would lower tariffs, and on immigration and education. What alarmed them most was the prospect that Trump would upgrade ties with Pakistan at India’s expense. That would inspire anti-Americanism in the Indian electorate and jeopardize Modi’s position. A quarter century of trust building would unravel overnight.

Modi is alarmed. To show his displeasure at U.S. policy, and remind audiences at home and abroad of India’s non-aligned streak, Modi joined Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit in Beijing in August. “Looks like we’ve lost India and Russia to deepest, darkest China,” Trump snarked on Truth Social in response. “May they have a long and prosperous future together!”

A phone call between Trump and Modi a couple of weeks later appeared to salve any diplomatic wounds. But the relationship is far from healed. Just this week, Washington and Delhi argued over whether Modi told Trump he’d reduce purchases of Russian oil.

What, then, is Trump up to? In India, explanations run the gamut. Some say he’s falling for a charm offensive by Pakistan’s Munir, who supported the president’s quest for the Nobel Peace Prize. Others speculate about lucrative business deals between Pakistan and the Trump family.

My explanation is different. It is that the strategic picture has changed. Where once Trump saw the US-India relationship as a means to contain China, he now sees it as a means to resolving another conflict. Thus, just as US-Indian relations suffered during the Cold War, the partnership is under renewed pressure as Trump tries to reduce Russia’s energy exports in his bid to bring Putin to the negotiating table in Ukraine.

And just as Indian-American relations nosedived when America sought to open China and thereby divide the Communist bloc in the 1970s, India today looks on as Trump pursues something resembling detente with China, wheeling and dealing over TikTok, strategic minerals, and critical supply chains.

In this sense, Trump’s revised stance toward India is just one aspect of his second-term foreign policy revolution, where the traditionally internationalist aspects of his first term have been abandoned for a more unilateral, realpolitik, even mercenary approach.

There are signs that Trump won’t go this far, that he will work to improve the relationship with India and mend ties. He and Modi have exchanged kind words over social media. The new ambassador to India, Sergio Gor, is close to the White House. The momentum from decades of people to people connections and democratic traditions has a life of its own.

And China isn’t going away. If America wants to define this century as we did the last, we will need friends. And a growing, energetic, subcontinental nation of 1.3 billion people, most of whom are under 40 years old, with a two-thousand-mile long border with an adversarial superpower, is the obvious place to find them.

Trump may have to pirouette and sway as part of his highwire balancing act. But there’s always the danger he trips and falls. Getting things right with India would make his job easier—and the world more prosperous and safe.