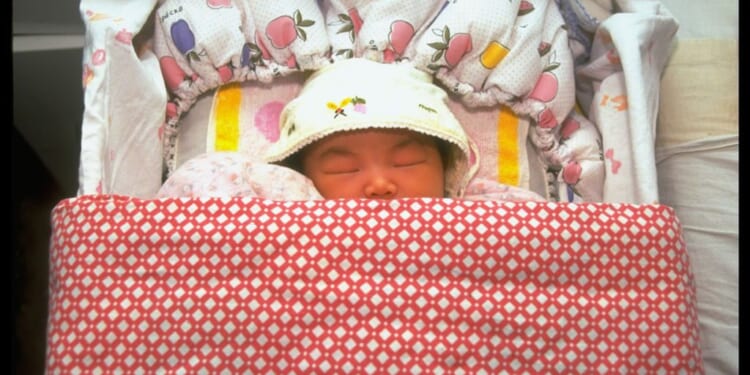

Megan was born addicted to heroin. Her tiny body convulsed from Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome when I first cradled her in the hospital’s special care unit. I fostered her from those earliest days, rocking her through the nights marked by guttural wails of withdrawal. I adopted her at two, after a matching panel and a celebration hearing, where social workers praised my “resilience” and handed me pamphlets on “building secure attachments”.

In the glossy adoption literature they talk about “therapeutic parenting”, “co-regulation”, and the healing power of unconditional love. No one mentions the times your 10 year old gives you a black eye so vivid that the pharmacist quietly hands you a domestic-violence leaflet. No one mentions the clumps of hair torn out at the root that never grow back, or the moment you lock yourself in the bathroom, heart hammering, wondering whether the next bang on the door will be her shoulder or a knife.

I have lived all of it. And so I read the news that 1,000 adopted children had been returned to care in England over five years with the dull, bone-weary recognition of someone who has stood barefoot in the hallway at two in the morning, blood trickling from a split lip after her daughter’s fists had found their mark again.

I know exactly how close my daughter has come to being one of those thousand. I have also lived the slow, corrosive shame of knowing that, in the darkest seconds, a part of me understands the parents who hand their children back. Not because they stopped loving them, but because they could no longer guarantee anyone’s safety, least of all the child’s own.

I can still remember the flicker of fear in the hallway, as we both sob and I dab at her scraped knuckles with a damp cloth. What if next time it’s not a fist? What if I can’t hold the line? Losing her would devastate me. Yet there have been nights when the physical and emotional onslaught, the constant hyper-vigilance, the marrow-deep exhaustion, has made me wonder, in the shadowed corner of my mind, whether the system that placed her with me even cares when I crack.

A widespread belief is that adoption offers a “fresh start”. It is a comforting fiction, an insistence that trauma is a knot to be untangled with the right words, not a brain permanently rewired by poison in the womb. The truth is that prenatal exposure to alcohol and drugs doesn’t just “increase the risk”; rather it carves permanent grooves into the developing brain, leaving invisible scars that shape a child’s impulses, emotions and choices for the rest of their lives.

An estimated three quarters of children adopted from care are at risk of having foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). It’s a condition which is almost always undiagnosed because the criteria require confirmed prenatal alcohol exposure — which mothers rarely admit — as well as specific facial features present in just 10% of cases. Many cases of FASD are misdiagnosed as ADHD, autism, or behavioural disorders.

Yet as I learnt first hand, if the damage wrought by FASD is invisible on a scan, it is explosive in a living room. The rages start small, a refusal over bedtime, a misplaced top, but quickly escalate, encompassing everything from hyper-arousal, and impulse-control collapse to fury that overwhelms without warning. These are neurological injuries, not moral failings or attachment deficits that can be cured by better parenting. Yet the entire post-adoption support system is built on the pretence that they are.

When Megan’s rages became daily — by four, she was excluded from nursery after biting and scratching teachers until they bled — I begged for the help that was promised in every pre-adoption briefing. But it never came. CAMHS waiting list: two years, a limbo of hold music and platitudes. Adoption Support Fund assessment: another year, buried under bureaucracy. In the meantime I was handed leaflets on “wondering aloud” (“I wonder if you’re feeling angry right now?”) and “time-ins” (sitting quietly together until the storm passes).

“She was excluded from nursery after biting and scratching teachers until they bled”

I was told I needed to “hold the space” for Megan’s pain, to become a human sponge for the toxicity she’d absorbed before birth. Yet holding the space is difficult when the space contains flying furniture, shattered plates, and the metallic tang of fear in your throat. I tried it all — from endless books on “trauma-informed care” to “PACE” training courses preaching “Playfulness, Acceptance, Curiosity, Empathy”. But books couldn’t soften the rages.

Eventually, after four years of pleading, desperate and hollow-eyed, I wrote to my MP. Only then did the Adoption Support Fund release £4,500 for equine therapy. I cried as I watched Megan, usually so coiled, lean into a pony, its steady warmth somehow reaching the part of her brain the alcohol had scarred, the part that lay beyond my reach. It has kept us together. Without it, we’d have been another disruption statistic.

This April, the Fund was cut by 40%, with the per-child allowance falling from £5,000 to £3,000 a year. Specialist FASD assessments were removed entirely. Families who have waited half a decade for help are now told the budget is exhausted, slamming the door on the very interventions that could prevent breakdowns. One social worker, a weary veteran of the trenches, asked me over a snatched coffee, with bitter laughter: “So the children are 40% less damaged this year, are they? Or are we just 40% more abandoned?”

This is not mere incompetence. It is a quiet decision by the British state that acknowledging the scale of prenatal alcohol damage is too politically fraught. That, after all, would require admitting that thousands of women drink heavily through pregnancy, often in the grip of addiction or despair, and which the welfare system has failed utterly to address. It would also oblige politicians to admit that the NHS has no reliable, standardised way of diagnosing the resulting disability, and that the “fresh start” narrative sold to prospective adopters is a comforting lie, one told to keep them flowing into a system in constant need of new recruits.

It is easier to keep insisting that with enough empathy, enough PACE acronyms, enough therapeutic re-parenting mantras, the child will eventually choose calm over chaos. But they can’t “choose”. The brain does not rewrite itself because a middle-aged woman learns to speak in a softer voice or validate their feelings.

I have watched friends reach the same precipice, their stories echoing mine. One, a woman I’d met in our draughty support group 11 years ago, locked her ten-year-old son on the porch when he came at his sister with a kitchen knife, eyes wild with the same undiagnosed FASD fury. Social workers arrived the next day and accused her of neglect. They recommended a parenting course. This woman’s child is now in residential care at £250,000 a year to the taxpayer. She is on antidepressants, her confidence shattered, still whispering to me on late-night calls that she “should have tried harder”.

Professor Laura Machin’s research at Lancaster University lays it bare: 38% of adoptive parents seriously consider asking for their child to be removed at some point, a tipping point where love and desperation collide. With proper neurological intervention, from early diagnosis to targeted therapies, that figure could be halved, sparing families and saving the state millions in downstream costs. Instead, we are cutting the only fund that pays for such vital work, outsourcing the fallout to private anguish and public expense.

There is a peculiar cruelty in asking ordinary families to absorb the lifelong consequences of addiction and neglect, then punishing them when the inevitable happens. We are told we are “giving a child a future” — but, in reality, we are being asked to mop up a public-health catastrophe, with prenatal alcohol abuse now the leading preventable cause of developmental disability in the UK, using nothing but love and grit. Then, when things go wrong, some are berated as being deficient parents, their pleas dismissed.

Megan is 13 now. Some weeks are calm. Some nights I still sleep with my bedroom door braced by a chair, listening for the creak of floorboards. I love her fiercely. But I have stopped believing that love is enough. The brain she was born with was shaped before I ever held her, scarred by substances no infant should know. No amount of devotion can unmake that first, irreversible injury.

When things get difficult, I still picture that newborn, rigid, clammy and craving the substances that flowed through her birth mother’s bloodstream. There are thousands of children like Megan, and thousands of parents barricading doors to keep themselves safe. What these children desperately need is support. Instead, the Government is walking away, and society’s most vulnerable children, my daughter among them, will pay the price.